As COVID-19 cases continue to rise around the country due to the highly contagious Delta variant, state governments, schools, corporations, and religious institutions are weighing vaccine mandates. Where there’s a vaccine mandate, there’s a protest, from California and Washington State to New York, and then come the debates over religious exemptions.

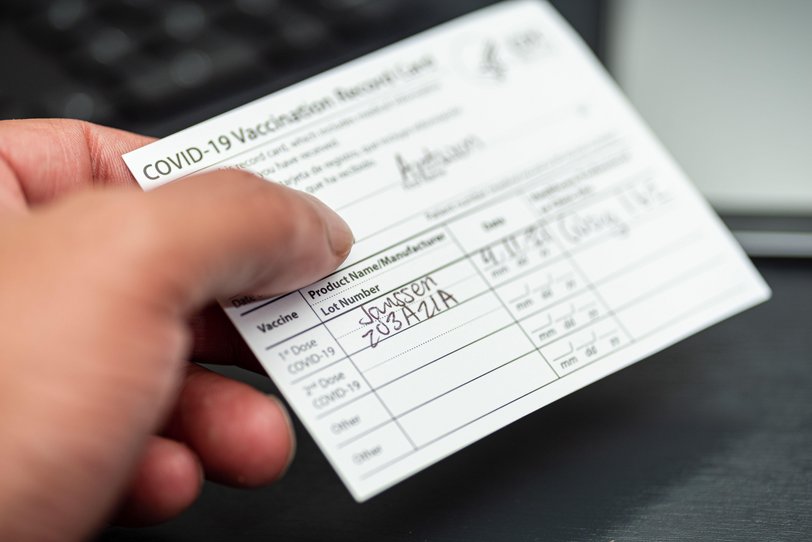

Under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, businesses are allowed to mandate vaccines so long as religious exemptions are offered to employees with “sincerely held religious beliefs.” According to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), if an employee applies for a religious exemption to a COVID-19 vaccine requirement, the “employer must provide a reasonable accommodation unless it would pose an undue hardship,” defined as “having more than minimal cost or burden on the employer.” “Reasonable accommodations” might include remote work, regular COVID-19 testing, or mask requirements. Public schools in 44 states also provide for religious exemptions to vaccines. But states and cities, historically the sources of vaccine mandates as opposed to the federal government, are not required to make religious exemptions.

Should religious exemptions to the COVID-19 vaccine mandates be allowed? Are exemptions the right of an individual, or do they threaten and thus impose on the rights of other people? Where do Buddhists stand?

Joy Brennan, assistant professor of religious studies at Kenyon College whose work focuses on Buddhism, tweeted on August 28 that she is adamantly opposed to religious exemptions for vaccine mandates.

As a religious studies professor I go on record as 100% opposed to religious exemptions for vaccination mandates, particularly at private institutions like my liberal arts college, which has granted such an exemption.

— Joy Brennan (@joycbrennan) August 28, 2021

From a legal perspective, judging the merit of a religious exemption is complicated, says Candy Gunther Brown, professor of religious studies at Indiana University.

For one, there’s no consistent standard for evaluating whether or not a religious belief is “sincerely held.” And “who’s to judge?” she adds.

“Some individuals do feel that they are being coerced to do something that’s a violation of their conscience,” Brown says, “and some people, perhaps many people, are using religious exemptions as an excuse that blurs easily with politics. But who’s to judge the sincerity? Who’s to disentangle what’s political and what’s religion, or what’s good science or bad science?”

In certain cases, a religious exemption may affect just one person, as in a Jehovah’s Witness refusing a blood transfusion because of his or her own beliefs. But an exemption for the COVID-19 vaccine affects many, and “the courts have tended to intervene in that because of the public good,” Brown says, referencing the precedent of New York State’s 2019 decision to end all exemptions except medical ones for the measles vaccine.

Still, it’s not so cut and dry, Brown says. Even though major religious leaders, including the Dalai Lama, have encouraged people to take the COVID-19 vaccine, and even though resisting the vaccine puts greater numbers at risk, it could be a slippery slope to ban religious exemptions altogether.

“The question is, could there be a future situation where the same kinds of arguments for public interest get used, but they’re applied in a manner that’s then more damaging to religious freedom?”

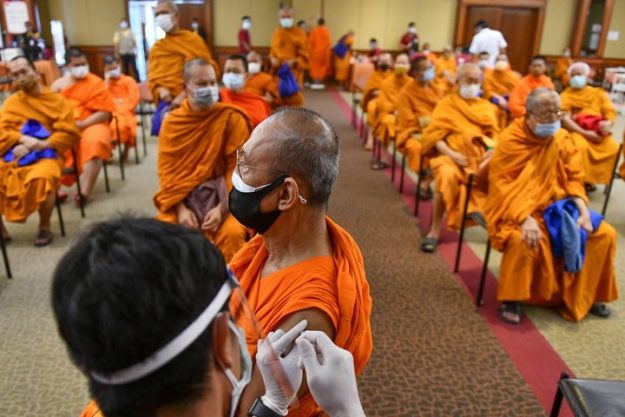

From a Buddhist perspective, Duncan Ryuken Williams, a Soto Zen Priest and Director of the Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture at the University of Southern California, supports vaccine mandates by recognizing Buddhism’s historical focus on preserving life and protecting one’s community.

“From the earliest codes of conduct for the Sangha, we Buddhists have emphasized the creation of a hygienic atmosphere for our community in respect for the health and welfare of others,” he says, calling vaccinations “a modern-day approach to preserving the lives of many sentient beings.”

He points out that some of the first people to take the COVID-19 vaccines in predominantly Buddhist countries were ordained Buddhist monastics, including the Dalai Lama. Duncan also calls on compassion and flexibility to accommodate those seeking medical exemptions. But he stops short of specifically supporting religious exemptions by instead returning to a focus on the greater good.

“As a matter of alleviating suffering, we Buddhists should not be hesitant about trying to assist with healing a global pandemic. While we must have a flexible and compassionate mind to allow exemptions for those for whom a vaccine is medically inadvisable, we can certainly support mandating the currently best-known method to create a healthier community.”

Brown reiterates this position by suggesting the Buddhist approach would be to move away from a rights-based argument and first consider society at large—calling upon the Buddhist principles of interdependence and compassion.

“The opportunity here that a lot of religious leaders are recognizing is to not be so focused on oneself or one’s own rights, but to be focused on others,” she says, and specifically those who may be the most vulnerable. “Sometimes giving up one’s rights actually makes a lot more sense than then insisting upon them.”

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.