Close your eyes

And become a mountain

Become all around you

Become the skies, become the seas

Open your eyes

And remain the mountain

Breathing in deeply

Feeling the day change with the breeze

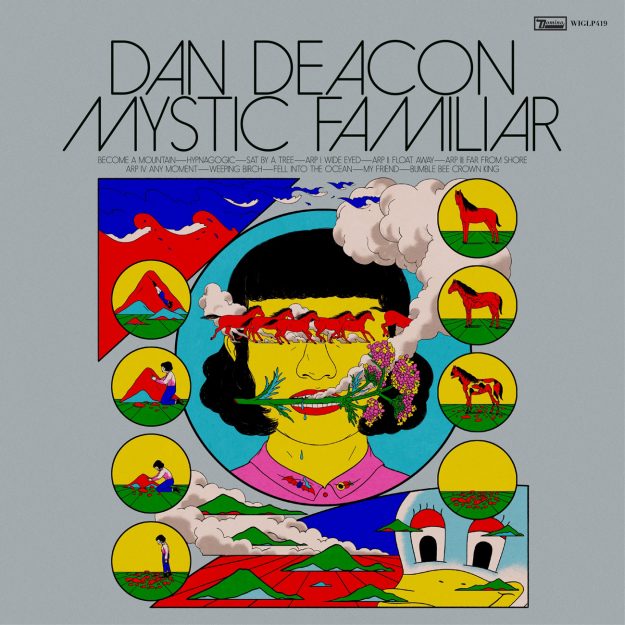

These lines could easily be mistaken for meditation instructions, but they’re lyrics from the opening track of Dan Deacon’s new album, Mystic Familiar, his first solo record since he released the critically acclaimed Gliss Riffer five years ago. Many things have changed for Deacon in that time—not least among them, he started meditating.

The electronic musician has long straddled the worlds of contemporary classical and independent pop music. With the release of his first studio album, Spiderman of the Rings, in 2007, Deacon became known for his unique live performances, with their innovative uses of audience participation, and his collaborations with the fellow members of the Baltimore-based artist collective Wham City. He went on to release four more studio albums, work with the So Percussion quintet, the Kronos Quartet, and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and compose several film scores, including Twixt (2011) by Francis Ford Coppola.

With Mystic Familiar, writes Pitchfork reviewer Andy Beta, Deacon infused his “manic, chewed-power-line indie pop … with a mystical inquiry into the nature of change and the mutability of nature.” This added dimension was born out of Deacon’s daily meditation practice.

I had the chance to speak with Deacon about his practice over the phone, and he was excited to discuss it as he was nervous about his lack of expertise. Deacon began meditating two years ago, but while he may not know a lot of Sanskrit or Pali terms, he describes his experiences with meditation with an incredible acuity—providing insight into the challenges and rewards of developing a new practice and incorporating it into one’s daily life and creative process.

I listened to your album, just as a fan, and I was struck by what seemed to be a lot of Buddhist themes. I reached out to your publicist on a hunch that you had a meditation practice, which turned out to be true. So I want to start off by asking, did you hope that your practice would come across in this album, or were you surprised to hear that someone listened to it and thought, “This sounds Buddhist”? I would put that in the surprise category, for sure. But I try to remember that everyone listens to music differently, and hears things based upon their past musical and life experience. Two people standing right next to each other listening to the same recording can have completely different reactions to it. I’m always excited when I hear how someone interprets the music differently than I thought one would.

When did you start meditating, and what brought you to it? I started maybe two years ago. I was in a period of artistic doubt, working in isolation, and I was looking to external stimulus for inspiration. And my schedule was in constant flux, traveling to different time zones and performing at weird hours.

I had many false starts with meditating before that, and thought I was incapable of doing it, that it was beyond my mental or physical limits. I wasn’t allowing myself the space to be bad at it. I’d thought that I had to just sit there with my head completely clear. That obviously didn’t happen. The paradigm shift was that it was OK to suck at meditating at first. When I realized I was bad at it, it was almost exciting, because that meant I just had to keep at it, a little bit every day—and not punish myself if I missed a day.

I used that app, Headspace, at first. I found it to be helpful having another voice say, “And if your mind wanders, just gently bring it right on back.” I’d be like, “How did you know? How did you know, Headspace man?” But eventually, I found it a little easier to try it on my own.

Do you have a particular method that you return to now, whether it’s MBSR (mindfulness-based stress reduction), zazen (Zen meditation), or shamatha (calm-abiding)? I’m really ignorant to almost everything you just said. It’s extremely new to me, and it has been a personal experience. When the offer for the interview came in, I went to the Tricycle website, and I had this mass flush of imposter syndrome, like, “I don’t know how to meditate. This is going to be an article exposing me as a fraud.”

Basically, I sit in a chair, take my glasses off, close my eyes, and start trying to focus on my breathing. That’s still remarkably challenging for me. My brain is all over the place, especially if I have coffee.

I don’t know if this counts—I also don’t know if it matters if it counts or not—but I have a really old computer and phone, and I used to get frustrated when they would take forever to load. But now I cherish those moments. I can set it aside, close my eyes, take some deep breaths, and do a scan up and down. Then, whenever I’m ready, I’ll look at the computer or phone, and it’s ready to go. I’ve been trying to steal all these micro-moments while meditating.

I’m extremely interested in learning more about different methods and practices. But I don’t want to purport myself as any sort of expert.

That answer is so surprising to me because the track titled “Sat by a Tree” off the new album seemed like an overt reference to Buddhism, since the Buddha attained enlightenment under a tree. What’s the story behind that song? I was sitting by this tree, and I was trying to meditate on being in its presence. I love to sit in nature and try to call upon it. But I try to remind myself that I’m going to instill human traits onto nature. The trees aren’t just stoic, wise creatures. There’s also going to be sarcastic asshole trees, funny jerk trees, and annoyed trees, as well. Eventually, it was like, “Look, dude. What do you want from me? I’m just a tree.” I was confounded. I was like, “Oh, this is not what I expected.” They’re like, “Well, I didn’t expect you to sit here either. I just work here.”

I realized I wasn’t even relaxing enough to know why I was meditating. I was meditating with an end goal in mind, but I didn’t know what that end goal was. I thought the sheer act of meditating would bring it on, if that makes any sense. Then, I started realizing that it wasn’t a capitalist exchange of meditation for inspiration.

The tree’s sarcasm was like, “What would you even want to do if you had the ability to relax?” If you’re on this quest to try to relax or be calm or make peace with yourself, what does that even mean to you, and why do you want it? What would the result of that be? That hit me like a ton of bricks and became the foundation of that track, which became the foundation of the record—this idea of getting questions from external entities.

The album’s name, Mystic Familiar, is a reference to those external voices. Where did that title come from? I was playing a lot of board games with friends, and one friend who’s a game designer used the term mystic familiar, and I was like, “What is that?” He said, “Like Merlin’s owl or a witch’s cat—some entity that can communicate with a human being in a supernatural capacity.” I got really into this concept and related it to the [creative] blockage I was having. I was trying to write music in my voice, but I felt very stifled and plugged up. But I thought that if I could put what I was trying to write into a character’s voice, into an external entity, it would be easier to articulate.

When I was feeling very low and very depressed, and doubting all my processes, it was very hard to have lyrics like “Become a mountain / become the sky / become the seas.” I was feeling like crap, so how was I supposed to scream these words out into the world and have them be real? But at the same time, it’s what I wanted to say.

Also, while meditating, an image would go through my mind of a cat sitting in the rain in the courtyard outside my studio window. Most of the time, a cat in the rain is like, “Get me out of here.” But I envisioned this cat just sitting very peacefully, emanating that all of time is right here, is right now. I don’t know if I would’ve come to some of these thoughts on my own. I know that’s weird to say, because they did enter into my brain, but for some reason, the idea of the familiar made it a lot easier.

There were two Buddhist musicians who I believe have been influential on you: John Cage and Philip Glass. Were you aware that meditation has been a pretty significant part of their lives? I don’t know if I knew if John Cage was Buddhist. I knew it was an aspect of Philip Glass’s life and approach to music. But like you said, their music—and John Cage’s writing and philosophy in general—was very influential on me.

From a musician’s standpoint, they both have very meditative qualities but in completely different ways. I’m drawn to the music of ’70s American minimalist—that maximalist approach to minimalism, a slowly shifting gradient of sound that you could just close your eyes and let envelop you. That’s what I like the most about making music. Having a loop and tweaking it until it falls into a completely new place, and time sort of stops passing. It becomes another thing, like the air in the room, and you get lost in it.

When I first started getting into John Cage’s music in college, I focused on the textures and the techniques he was using. But after a while, I started thinking more about the spacial relationship of the sound, and it became really meditative for me. I’d been wondering about how and why, but I wouldn’t sit in front of a beautiful lake and ask how or why. Cage’s and Glass’s music got me into just appreciating music and how it colored the air.

What do you think it was about their music that let you stop attacking it with your analytic mind? Probably its sheer beauty.

One of my favorite things to do is go tubing down a river for as long as possible, and see where it takes me and how it’s constantly shifting, every turn different from the next. I go to the same creeks multiple times each year and see the different accumulation of fallen trees and the changes in the water level. There’s a microstructure that, if you pay attention to or open yourself up to, exposes itself. Cage’s and Glass’s music has that same quality, where the macrostructure is beautiful and intriguing, but when you let it fully envelop you, you start hearing all of this nuance that could easily be lost if your mind is elsewhere, or too analytical, or fixated on what’s going to happen next.

I try to approach my own music with that in mind. I want there to be a macrostructure that you can easily latch onto, which is why I write mostly in pop music structures, but I also want you to be able to find all of the various layers, micro fluctuations, and constant gradient changes. That’s what fascinates me the most about minimalism and Cage’s approach to space, sound, and silence.

Yeah, when a piece starts off with a phrase that’s easy to grasp and you can watch it build until it’s so complex and overwhelming that you can’t fully get a handle on it—that can bring you to a spiritual place. Absolutely. I feel like it also can have the exact opposite effect, where it can be really overwhelming at first—especially [Glass’s 1976 opera] Einstein on the Beach, which can be so frantic and jarring—but once you embrace the flow, it can be very, very soothing. And a pattern emerges. The frantic pacing becomes almost like a super slow pulse, rather than a rapid-fire succession of sounds.

You got into meditation practice in between your last album and this one. Meanwhile, you scored several films and performed around the world. At a time when my life was all about my career, something that resonated with me was the phrase, “Zen is good for nothing.” It’s pointless. You end up exactly where you started, but you just do it. I found that very valuable. When you started meditating, did you have a sense that it was inherently non-careerist? Yes. As soon as you said, “meditation is good for nothing,” I was like, “Oh, good, because nothing could really use something going for it right now.” Nothing gets a bad wrap.

I know exactly what you mean. In the music business, you catch a wave, and you ride it as long as you can. That wave eventually is going to break, and if you can swim back out, hopefully you’ll catch another wave that’ll crest. Pursuing every dangling carrot can be exhausting and disheartening. I got into making music because it was my favorite thing to do. What I didn’t realize was how my hobby would change when it became attached to economic consequence and obligations. I’ve had to make an active, conscious effort to remember that, even if I’ve been writing all day for quote-unquote work, I have to embrace the hobby aspect of it.

That’s what this record was, at first. I was doing all these film scores and collaborations, and I cherished any moment I could steal to write music for myself. But as the record started taking form, it shifted from pure hobby into a project, and my relationship with it changed. I had to be conscious of that. I had to start each day meditating on how much I love that this is my job. I still struggle with being a professional artist and someone whose main hobby, source of relaxation, and period of mental self-care, is writing music. But I think knowing that I need to set that intention helps me quite a bit.

That’s why I tried to start each day meditating, and I would interrupt the studio process quite a bit to do it.

What did these breaks in the studio look like? My studio’s in my house, and my partner works during the day, so I’m in the house by myself all day working on this record. Sometimes I wonder, “Have I started working on the record the moment I woke up, because it’s the first thing I think about?” When I’m making coffee or eating breakfast, I wasn’t thinking about eating. I was thinking about how I’m going to go upstairs immediately afterward, and which file I’ll open or what instrument I’ll set up.

If I found myself thinking like, “Can I even envision playing this on a festival stage? What will a reviewer think while they’re listening to it?” Thoughts like these are the spikes in the road to my inspiration. So, I would stop, and I would try to center my thoughts on being present, not worrying about what the sounds will be but what the sounds are. That really helped to get me out of my head and into the studio more.

Whenever I realized that I was lost in a loop or anxiety that was turning my excitement about recording into dreading deadlines, I could hit the pause button on the screaming chatter in my head, or just let the thoughts pass by. Sometimes, I would just push the chair back from the desk and try to meditate without setting any time limits on it.

It also made it easier to be OK with not knowing what to do next. I found it was more exciting to be like, “I don’t know what these choices can be,” and to just allow myself to go with the flow. Otherwise, I was too tense. It was like trying to control the weather. It’s impossible. It can’t be done.

On your previous albums, you already seemed to have an interest in more spiritual questions. The track “When I Was Done Dying,” for example, reminded me of descriptions of bardo, or the state between this life and the next, in Tibetan Buddhism. Where does this interest in death, or what Buddhists would call impermanence, come from? Well, my mother died when I was in high school, and I grappled with that for a while. She had cancer, and it was a rough go. I was raised Catholic, but was no longer identifying with being Catholic at that point in my life. As a kid, growing up Christian or Catholic, when someone dies, people say, “Oh, you’ll see them in heaven.” As I got older, I kept wondering, What would that be? What form would my mother take, and what would she have been up to in the time between? Would it be an infinity of eternities, or would it have been a blink of an eye? I don’t know. I became fixated on that idea in my lyrics. I used to cloak it. My [2009] album Bromst is largely a concept album about someone becoming a ghost and the anxiety of becoming a new entity. But I don’t think anyone would’ve known that Bromst was a concept album. I never stated it when the record came out. It was just for me.

The title for “When I Was Done Dying” revolves around something my younger siblings would say when they would see photographs from before they were born. They would refer to it as when they were dead, using that little kid logic of “If I’m not alive, I’m dead. So before I was born, I was dead.” Everyone would laugh and be like, “You were never dead,” but they’d be like, “Yeah, but I wasn’t born, so I was dead!” That really stuck with me. People tend to have a lot of anxiety about what will happen in the future when we no longer exist on this earth, but I wonder if I went through a period of anxiety before I was born, like, “Oh my God, I’m going to be born. What am I going to do? What is existence going to be like? I don’t know. What if it’s nothing?”

That’s why I don’t see death as much of a negative. It’s impossible for me to understand what my life would’ve been like if my mother hadn’t died, or what her life would’ve been like, or if I wasn’t born, or if she weren’t born. It’s not for me to speculate. When someone you care about leaves your life earlier than they should, especially at a young age, you learn their life isn’t defined by their death.

While thinking about it sometimes brings me great sadness, it’s also utterly inevitable. To feel loss is beautiful and profound. That you can only feel loss for something that truly, truly meant so much to you—it’s so wonderfully lucky to have something that could mean so much in the first place.

Wow, yeah. Cycles, such as the water cycle, are a theme on the new album. Do you have opinions on reincarnation? Is that something you think about? I do. I think about it quite a bit. I don’t know what will happen—obviously, I don’t know. Like I said, I’m a bit out of my depth. I feel like I’ve been brought onto a cooking show, but I only just figured out that you could add spices to make the food kind of tasty.

All your questions were really inspiring for me, and I really appreciate you taking the time to ask me them and being cool about my ignorance to something that means so much to so many people. Hearing all the parallels that you’re finding in my work to existing Buddhist texts—I’m really excited to check them out, because these are clearly thoughts that I’m having, and I’d love to put context to them.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.