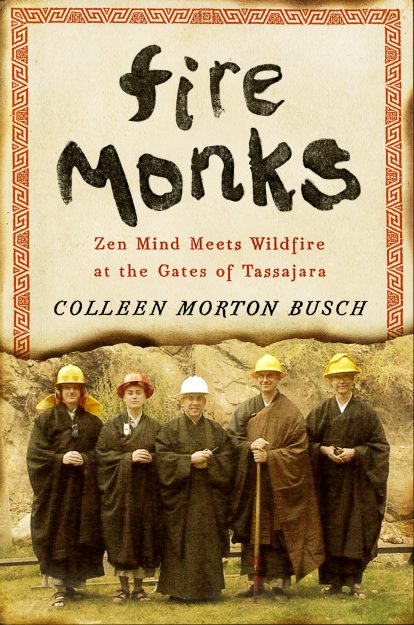

Colleen Morton Busch is the author of Fire Monks: Zen Mind Meets Wildfire at the Gates of Tassajara. She has practiced in the Soto Zen tradition for many years and currently serves on the board at the Berkeley Zen Center. Fire Monks is featured in the current issue’s “Books in Brief.” We were recently able to chat over email about Zen, fire, and the relationship between the two.

Ultimately the monks at Tassajara managed to save their monastery. But the Tassajara after the fire was not the same Tassajara as before the fire. What was lost? It’s not so much that something was lost, but there was a Tassajara before the fire and a Tassajara after the fire. Several buildings burned down. The mountains were stripped bare. Some animals—like raccoons, formerly ubiquitous—haven’t really returned. But within a few weeks, new shoots sprouted up at the bases of burned trees and chaparral. Wildflowers appeared that spring that only bloom after fires. Structures that burned were rebuilt. In the community, as in the landscape, there were burned areas and patches of vivid new growth. Some were inspired by the way they had pulled together; others felt a lingering pain of separation from the evacuation. Gain and loss are always happening together, always flowing simultaneously, like life and death.

Ultimately the monks at Tassajara managed to save their monastery. But the Tassajara after the fire was not the same Tassajara as before the fire. What was lost? It’s not so much that something was lost, but there was a Tassajara before the fire and a Tassajara after the fire. Several buildings burned down. The mountains were stripped bare. Some animals—like raccoons, formerly ubiquitous—haven’t really returned. But within a few weeks, new shoots sprouted up at the bases of burned trees and chaparral. Wildflowers appeared that spring that only bloom after fires. Structures that burned were rebuilt. In the community, as in the landscape, there were burned areas and patches of vivid new growth. Some were inspired by the way they had pulled together; others felt a lingering pain of separation from the evacuation. Gain and loss are always happening together, always flowing simultaneously, like life and death.

Tell me about their decision to stay. Actually, they intended to stay from the very beginning, but how they renewed that decision on Tassajara Road during the final evacuation is the question that led me to want to write Fire Monks. I’ve stood at that spot and know that road. I wondered, What would I have done? How did they know what to do?

Intuition is a complicated, mysterious process. It’s hard to unpack or analyze. There’s no recipe. I tried to illuminate it instead, to show how their decision didn’t discount thinking but didn’t entirely originate from a thinking place either. They made the choice to stay with their whole bodies, with their hearts and with their intelligence about Tassajara and the preparations they’d made—nothing left out of the equation. They made it as individuals with unique histories and also as a community with shared experience.

I do believe that zazen practice helped, by fostering a willingness to be with the unknown, a dropping off of the concerns of the self, an opening of the gates of perception. The five who stayed at Tassajara describe their choice to stay not so much as a decision but as a response to the total circumstances of the moment.

Why save the monastery? That is, what would have happened had Tassajara burned down? They would have mourned, and then they would have rebuilt.

I’m often asked: Isn’t it hypocritical for Buddhists, who practice nonattachment, to expend so much effort saving something material? Nonattachment doesn’t mean detachment. It isn’t indifference. Part of Zen practice is taking care of what’s in front of you, whether it’s a pot of rice or a monastery threatened by wildfire. There is nothing that is not deserving of respect or attention. To put the kind of effort the residents put into protecting Tassajara without any guarantee that their efforts would indeed save it—to me, that’s true nonattachment.

The monks lacked training in firefighting. How did their Zen training prepare them for the wildfire? Meditation cultivates composure, the ability to meet whatever comes and not panic. A wildland fire investigator named Ted Putnam is teaching meditation to firefighters because, after years of studying fatalities and practicing meditation himself, he believes meditation will enhance firefighter safety.

Their tools may differ, but there are actually quite a few similarities between monks and firefighters. They live together in close quarters, in intimate contact with life and death. They put others before self—or at least they vow to. They endure discomfort and deprivation. Daily, they take up the difficult practice of paying attention, staying open to new information, recognizing impermanence. When firefighters get into trouble, it’s often due to a lapse in what’s known as “situational awareness.” You could say the same of Zen monks!

Fire Monks is a book about real-world spiritual practice and a real wildfire. However, fire is also an important symbol in the Buddhist tradition. And readers can draw spiritual nourishment from this story by using the wildfire as a symbol for the unexpected and dangerous. What’s the difference between the real thing and the symbol? What’s the relationship between them? Because I trained as a poet, the real and the symbolic aren’t so much different to me as complementary, a reflection of how we experience the world.

A “real” fire can burn, so it’s important to treat it with respect, have the right tools, do the work that needs to be done to stay safe, have adequate water on hand. You can’t sweet talk a wildfire.

If the “fire” is a life-threatening illness, the above still applies. You need to treat it with respect, equip yourself to meet it, and sometimes you need powerful chemicals to tamp it down. You can’t sweet talk cancer, either. But instead of fixating on the fire or the illness as an enemy, you can meet it with a calm, flexible mind and open heart, as part of you, not something separate from you that has lodged into your life like a thorn.

Did the Buddhist teaching of right speech influence your telling of the tale? Yes. I wanted to tell the story as accurately and completely and engagingly as possible, and also to do it with respect and compassion. I cared about my relationships with the people and the place I was writing about. I put a lot of effort into building trust. For me, these various intentions weren’t at odds with each other. They kept each other in balance.

From the beginning, some members of the community were less than enthusiastic about this story being made into a book, though their reasons varied, and the intensity of their hesitation. I tried to find ways to both obtain the story and honor people’s wishes. There were members of the community who I wanted to include who declined to be interviewed. In one case, I felt very strongly that the individual’s story—he was one person who chose not to return to meet the fire—had to be included because it would resonate with readers as an understandable choice, demonstrate another kind of courage. I just kept going back to this individual, telling him that I was going to include his story and saying, Wouldn’t you prefer that it be in your own words?

I was aware from the very beginning of the limits of language—that I would trip and fall, anger people or hurt them despite my best intentions and effort, because words are open to interpretation and shaped by subjective views. But that didn’t stop me. As a writer, I hoped that there would also be people for whom Fire Monks would create connection and understanding. And I’m deeply grateful that that has mostly been the case since the book’s publication.

There is a famous photograph of a Vietnamese Zen monk on fire in the middle of an intersection. Even though this isn’t a subject you address in Fire Monks, I’m curious, what are your thoughts on self-immolation? That photo is astonishing. It captures a presence of mind and firmness of intention that is remarkable. I think of how I’ve squirmed in sesshin when my knees are on fire with pain, and this monk is sitting still as a stone, engulfed in actual flames. He is beyond pain, beyond self, beyond body and mind.

In Zen, there’s a well-known phrase: Practice as if your head were on fire. That teaching is often understood to point to a quality captured in the famous photo of the burning monk—a great imperturbability. But the head-on-fire phrase also reminds us that in life, there is no time to waste. It’s a call to wake-up, right now, before life passes you by. That particular monk’s practice was to burn up his life to make a political statement. That was his choice, just as it was the choice of several residents at Tassajara to stay when they were told to leave. As for the karmic consequences of these choices, I don’t know. None of us can know when we make a choice what the result will be. And we can never fully know another’s path.

But we can have empathy. In Fire Monks, there are political fires, the fires of thoughts, emotions, and opinions, the fires of human relationships, the fires of personal histories, the wildfire in the forest. I tried to include all of these fires, to show how they all burned together at once.

Read more about Fire Monks here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.