Jeongkwan Seunim’s everyday life looks somewhat different from life in other temples. That’s because the Netflix documentary about her brought her to worldwide fame overnight. And it had some consequences. In Korean temples, all seunims (Korean: 스님, Buddhist monks and nuns) lead strictly regulated lives apart from when they’re ill. Their days are divided up and times are scheduled in accordance with a daily rhythm: get up, participate in yebul or rituals, eat, study, work, meditate, receive visitors, and go to bed.

Jeongkwan Seunim, however, must organize her day quite differently if she wants to complete all of the tasks she wishes to complete and those that are expected of her. She accepts many additional tasks and meets with people who seek spiritual or life advice from her, and she also meditates with others. If all of that weren’t enough, she has become an ambassador for temple food, a role that often takes her on the road. She receives numerous invitations from other countries, and the government sends her abroad; she gives cooking classes and holds lectures in many different places. But her primary duty is being responsible for her temple and for the guests who come to visit her. There’s a lot to do, even on days when there are no visitors! Her hands are seldom idle.

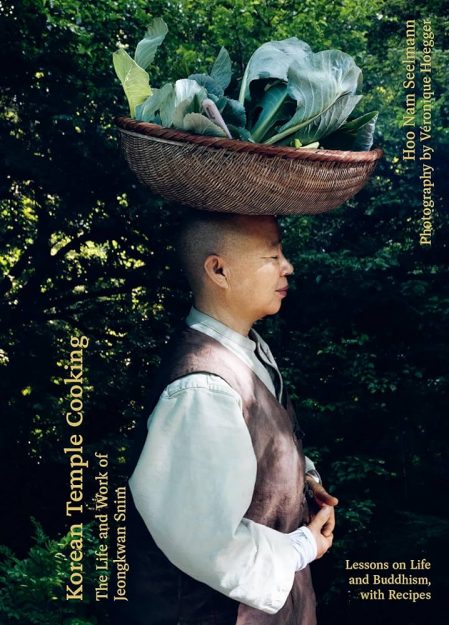

Snim speaks often of the significance of hands. They possess power, skill, and beauty, and they enable us to live life by creating a connection to the world. Hands can deliver hard blows and even kill, but they also carry a lot of warmth and are ready to reach out at any time to help others or offer someone support. A touch of the hand appeals to the humanity in us, and in fact babies cannot develop into emotional beings if they are deprived of touch.

The most important thing that hands do, however, is provide us with food. Snim says that they transfer our life energy into the ingredients. We are one with nature because our energy penetrates natural ingredients and forms them into dishes. In an interview with the New York Times, she said that “I become the cucumber, and the cucumber becomes me” when she prepares and eats something from the cucumbers she has grown in the garden.

When it comes to food, our own energy meets with the energy of nature, and together they form a single unit. Therein lies the magic that hands work: we incorporate nature into ourselves, and nature then becomes part of us. Our view of things is also important, as Snim says: “When you think of napa cabbage, don’t just see it as a vegetable, but consider as well that it will become a part of your body and your self. So, the cabbage becomes the self. This means that it should be handled with the same care and delicacy as if it were your own body. If you make kimchi with this mindset, it will be good.”

Therein lies the magic that hands work: we incorporate nature into ourselves, and nature then becomes part of us.

Snim’s hands are slightly plump and not especially large, but her hands are nonetheless powerful. Her palms have lost some of their suppleness because objects, water, heat, and steam have taken the softness from her hands and somewhat faded the enigmatic lines that adorn all hands. Snim has prepared countless dishes for many people all over the world; it’s as if you can see the traces of every one of those dishes in her hands.

Snim tells how she handles vegetables when she’s in the garden or the kitchen. “You have to be familiar with the individual plants in order to be able to prepare them well,” she says. “When they grow, when they bloom, how they taste at what stage, when is the best moment to harvest them. That depends on whether something is tender, tough, or bitter, on whether it tastes sweet or sour.”

When she cuts ingredients like squash, bamboo shoot, or lotus root, she shows the cross section and remarks on how diverse and incomparably beautiful it is. If she has a basket full of various kinds of greens, she’ll pick up this or that and take a bite to test its flavor. One wonders just how much knowledge she has to share!

“Many plants contain substances that are toxic for us humans and other animals,” she explains. “This is because all living things want to stay alive and protect themselves from others. This is completely natural and is a basic principle of life. It is not only animals that defend themselves—so do plants. They produce substances or chemicals that can be toxic. You also have to know that these substances can vary in strength through each stage of growth. When a plant is blossoming and when fruits form and ripen, the effect is the strongest, which means that the toxicity for others is the greatest.

“The goal of plant life is to leave fruits to ensure the plant’s own survival. When you want to prepare vegetables, it’s important to be aware of these circumstances so that you can neutralize the harmful effects and prepare healthy food from the ingredients. Much has to be controlled in the method of food preparation. You can cook, blanch, or steam the vegetables, but you can also season them with certain fermented flavorings.”

In Snim’s view, not only do soy sauce and soybean paste make vegetables tastier, they help neutralize unwholesome elements and aid digestion. They also stimulate gut flora. Listening to her, you realize how complex the process of living and surviving in nature is.

Snim loves vegetables and knows all about them. Korean temple cooking plays to her strengths, because temple food in Korean is called chaesik, which basically means “plant-based food.” The Western word “vegan” is close in meaning. Because temples are located in the mountains, inhabitants there have collected wild vegetables, mushrooms, roots, nuts, and fruits on the mountain slopes since ancient times. There’s such a great variety! And the flavors are incomparable.

Snim likes to talk about vegetables when she has free time. She says that every type of vegetable has its own special characteristics. The varieties differ from one another not only in form and color, but also in their fibrousness. That means it’s not always a good idea to cut everything with a knife—for some kinds of vegetables, whether you start with it raw or after it’s been blanched or steamed, it’s better to rip or pull it apart with your fingers. Only vegetables that you can’t handle with your fingers should be cut with a knife.

Fingers are essential to cooking because of their agility, sensitivity, tactile sense, and subtle ability to feel. Fingers do the work and conjure up good food, she says. Although because the palms usually contain too much warmth, it’s advisable not to handle ingredients for too long.

The Korean view of food as medicine is best preserved in temple cooking. Because they’re secluded in the mountains, seunims must acquire a lot of medical knowledge to maintain their health and to heal themselves when they become ill. For this reason, most seunims have historically had a good understanding of the curative effects of everything people eat. Since the foods differ in their ingredients, each of them has a different effect on us. It’s a wonder that we can obtain such diverse nutrients and elements from the soil! And that we can integrate them into our own growth and transform them into other substances and nourish ourselves with them…

…The food that Snim prepares is based on the long-standing traditions of Korean temple cooking, which have from the beginning been guided by Buddhism. If you see Snim cooking and talking, you can sense the presence of this inherited spirit of Buddhism. When she announces a meal, she says “Be healthy” (Korean: 건강하세요, geonganghaseyo). In other, larger temples where many seunims live, the wooden percussion instrument (Korean: 목탁, moktak) calls everyone to eat. You also hear the word gongyang three times a day when you live in a temple—it’s an old Buddhist word that’s uncommon outside of temple grounds. Gongyang represents respectfully offering the meal that has been prepared with care and devotion. It also resonates with a certain celebratory spirit and with an appreciation for the food that gives us life.

It’s no coincidence that according to Buddhism, the entire universe is contained within a single grain of rice. This concept is more than just symbolic: the grain of rice contains the power of the soil, the sunlight, the rain, the wind, the moonlight, the fog, and the dew. The final step is the energy that humans infuse the grain with through their work. We must sense the mysterious power concealed therein, and we must view the grain as being something valuable, and we must handle it with respect. This attitude applies not only to the rice but to all of the ingredients we use to prepare food.

The temple regulates who is responsible for the food. It’s usually the haengjas, or those who are completing a probationary period and the novices who begin their temple lives in this way. Each one must perform work in the temple kitchen for a specified period of time. On one hand, kitchen work is a lesson in service and humility, and on the other hand, it teaches that all work is of equal value. Cooking for others sharpens an awareness of what it means to be there for others and for the community.

◆

Excerpt from Korean Temple Cooking: Lessons on Life and Buddhism, with Recipes, the Life and Work of Jeongkwan Snim by Hoo Nam Seelman with photography by Véronique Hoegger. Published by Hardie Grant North America – September 2025.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.