Between-States: Conversations About Bardo and Life

In Tibetan Buddhism, “bardo” is a between-state. The passage from death to rebirth is a bardo, as well as the journey from birth to death. The conversations in “Between-States” explore bardo concepts like acceptance, interconnectedness, and impermanence in relation to children and parents, marriage and friendship, and work and creativity, illuminating the possibilities for discovering new ways of seeing and finding lasting happiness as we travel through life.

***

“Typically, I spend ninety percent of my writing time doing nothing but making tea and watching the hour-hand move,” John McPhee says. Toward the end of his writing day, he transitions into what he calls “the zone,” a period he compares to when basketball players are “hitting one shot after another” (versus not being able to “hit the broad side of a barn”). When he emerges from the zone, McPhee says, “It’s like waking up from a dream. You suddenly find out you’re there in your own room, and you thought you were wandering around a trout stream somewhere.”

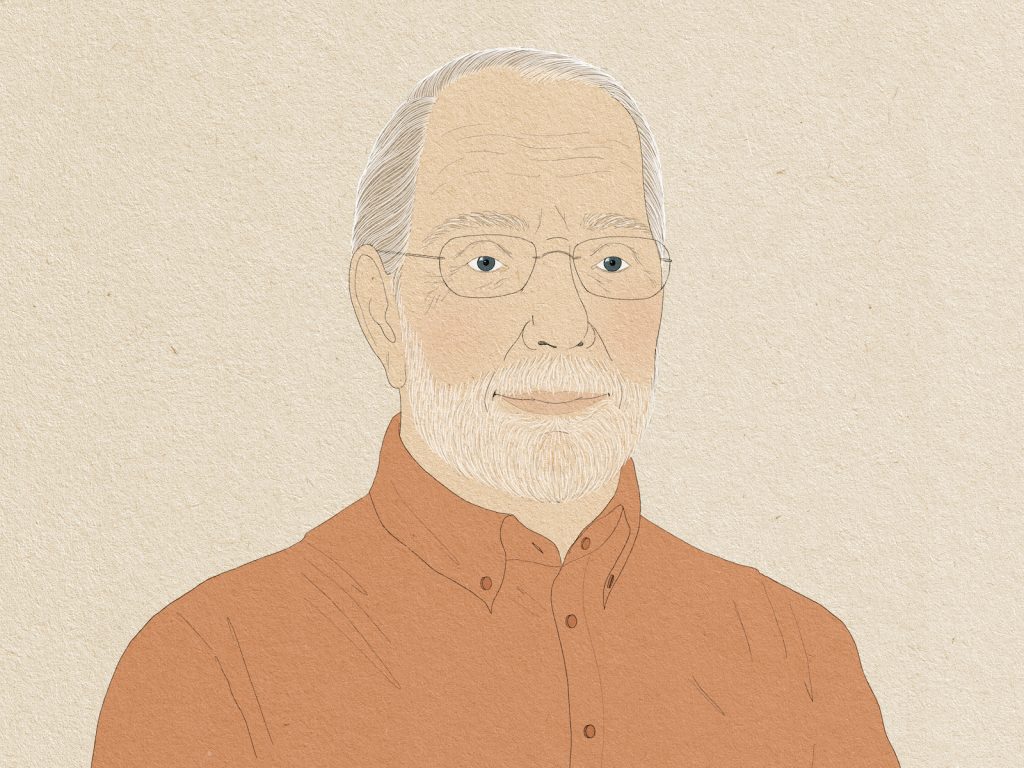

A New Yorker staff writer since 1965, McPhee won the Pulitzer Prize for General Nonfiction in 1999 for his nearly 700-page book on geology, Annals of the Former World. Other honors include a Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Book Critics Circle and an Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. McPhee has written thirty-three books, on topics ranging from Hall of Fame basketball legend Bill Bradley to orange farming to birch-bark canoes to Russian art.

He has lived in Princeton, New Jersey, where he was born, for most of his life. In 1975, he began teaching a creative nonfiction class at Princeton University, and many of his former students have become well-known writers. Now 91, McPhee no longer teaches, but he still writes and enjoys long-distance bike rides and fishing. These days, he’s working on a series called Tabula Rasa, memoir-type vignettes for the New Yorker about writing projects he intended to do but never did; the first volume of the collected pieces will be published next summer. Tabula Rasa is an “old-man project,” McPhee says, meant to keep him going.

On a morning in early fall, McPhee spoke with me over Zoom about writer’s block, entering the zone, and how coming to understand “deep time” (a term for geologic time that he coined in Annals of the Former World) gave him a new perspective on impermanence.

*

Bardo between-states include intervals when our ordinary reality is suspended, like when we go into the zone while doing creative work. What are your writing sessions like? I have a terrible time getting started. I might be at my desk from nine o’clock in the morning until three or four in the afternoon, getting nothing done and pacing around and making up excuses for not writing, sharpening pencils and so forth.

In Draft No. 4, your 2017 book about the writing process, you talk about the “animal sense of being hunted” that you experience. Every day I get up and brush my teeth, and then I go to write, and I overcome writer’s block. For me, it functions daily. There’s that membrane, as I call it, something I’m trying to break through each time a writing session comes up.

It can be hard to stay focused even after you get started writing. Does your mind wander? That’s a good point and question. My mind wanders all over the place all the time. But not that much. And once I go across the boundary and into the zone, there’s a great deal less distraction.

How would you describe the zone? When I finally get going, I go into a different world. One of the things that gets me there is panic. I think I’m going to lose the whole day, and that helps. But at all events, I go across a borderline—it seems like a barricade each day—and once the writing starts to happen, and I’m concentrating on it, and not worrying about whether I’m going to do it or not, I go into a different zone of mentality in which I lose complete track of time. I have to be pulled out of the writing, as opposed to initiating the escape.

Over the years, you’ve developed ways of getting into the zone. In the precomputer era, you used a typewriter to copy notes from your notebooks, coded the notes, photocopied them, cut them into slivers, sorted them into piles, and so on. In Draft No. 4, you explain that this laborious process painted you into a corner but freed you to write. What I’m saying has to do with the elaborate business of typing and retyping and studying notes and building structures, all before actual writing. I said that every year to my classes, about outlining and all. I said, “Look, this sounds very mechanical. It sounds like rote. However, if you go through your notes and so forth, when you’re done, you know where you want to go, and how and with what.” You know where you’re going to go, and therefore you’re not fettered by any thought about organizational stuff. You’re free to write.

Of course, you use a computer now. But it’s still all about establishing the structure. Yes. Another thing I always do, and always suggested to my classes, is that I write a lead. That really primes the pump. Just out of nowhere, without referring to notes or anything else, back toward the beginning of the process, I write the first…page? Two pages? Three? It depends. I wrote a lead once that was three thousand words, but it was the beginning of a book that was fifty thousand words. And the point is that when you look at something you’ve written that you intend as the beginning of your piece, and you decide that you like it, that it’s a good beginning and you want to keep it, you’ve got one foot on the beach. Then, when you go to look at all the notes and do all the structuring and the rest of it, it’s much easier. It’s all hanging like a Calder from that beginning.

So you write the lead before you figure out the structure. Every time.

Are there any projects you’ve abandoned midstream? How do you know when to let go and when to keep going? I’ve always been extremely reluctant to give something up, because of the sense that I might just give everything up after that. You might get out of the struggles with piece A, thinking, “Oh well, the hell with it! I’m not going to do it anymore.” And then you’re on piece B and you get to the same kind of crisis, and you give it up. That’s a very dreary glance into the future, and that thought has kept me at it. By the time I’m actually writing after collecting notes and everything else, I know if there’s a piece. It would be really a bad idea to quit. Pieces that I have quit, which are numerous—Tabula Rasa shows that—are quit at very early stages. I realized that for one reason or another they weren’t going to work, or I lost interest, and it wasn’t too late. Once you get into it and have your notes and everything else, and see there’s a story there, that’s when it would be dangerous.

What’s the most challenging project you’ve worked on? The geology book, Annals of the Former World. I didn’t realize what I was getting into, and it took twenty years. I’m awfully glad that happened, for all kinds of reasons, personal reasons about understanding the planet and so on. I’d taken a course in geology in my high school days, and it was all about geomorphology, and I thought I would write a “Talk of the Town” piece for the New Yorker about some rock outcrop outside New York City and be done with it, over in a day. But that idea grew from right there, changing to another related idea. The upshot was that I was going all the way across the United States on many occasions in the next twenty years, and Annals of the Former World is the result. It’s unique in my experience of projects. Only one took that long.

Twenty years is a long time. Did you ever feel lost along the way? I did other things. I started in 1978 and ended in 1998, but during that time, I wrote probably four or five books on different subjects, like the Deltoid Pumpkin Seed.

According to legend, the bardo teachings were hidden in a cave in Tibet, as well as in trees and lakes and the sky, in dreams and the mind. Their wisdom—for example, awareness of impermanence—is accessible if you have the right perspective. You might find it, say, in the geography of the mind. This idea often strikes me when I’m writing, because you’re in your mind as you’re working, exploring its geography. When you’re at your desk, in the zone, do you feel like you’re penetrating layers of your mind, venturing into uncharted areas and discovering new perspectives? I think I do. I’d have to think a long time about this, but the first thing that occurs to me is geologic time. And this kind of time wasn’t just something I gradually got a sense of in the field. I think the writing has done it, too. I remember [American geologist] Eldridge Moores saying that it took a long while with students, grad students, and everyone else in geology to get to the point of comprehending what a million years is versus our lifetime. In geology, a million years is nothing much. And I’ve developed that sense of time, what I call “deep time” in Book 1 of Annals of the Former World, “Basin and Range.” By writing about it and living with it for years, I’ve gotten a very different sense of time, of human time versus geologic time. I’ve received quite a few letters from cancer patients, about how it changed their perspective on death to read that section and find out about deep time—it’s that kind of effect that it has. But it hasn’t made me any less fearful of dying!

In the bardo of writing, and of life, we determine the nature of our experience with our choices. Looking back over the years at your trajectory as a writer, how do you feel about the choices you’ve made that have determined your path? When I was in college, they didn’t teach anything about nonfiction writing per se, let alone have factual writing in the creative writing program. I decided to write a creative thesis—which was fiction, because there was no nonfiction—and it was the second creative thesis in the history of Princeton. [Former New Yorker editor] William Shawn used to say, “It’s taking longer now for writers to figure out what kinds of writers they are.” In any case, I think young writers should try everything and then get into the niche where they are most comfortable. I’ve known writers who belonged in one niche and were trying to function in another—some writers think they ought to be poets, and they really should be novelists, or whatever. I got interested ever less in writing fiction, and ever more in writing nonfiction, as we call it, and I feel it’s where I belong. I’m completely comfortable in having chosen that niche.

Is there anything you would do differently? No. I feel really, really lucky. And nowadays, with the Tabula Rasa pieces, I’m experiencing a sort of counterpoint to the struggles of the writing process. I enter the zone as soon as I sit down. It’s like when a basketball player is in the zone—he’s spaced-out confident that he’s playing at his best, and he’s not half thinking about it, it’s just happening. Everything is going to go right, and you just know it’s going to go right. And that’s what practice is all about. The more you do something, the better you should become at it. Somebody who shoots a thousand shots at the basket per day in practice is probably going to have better muscle memory than other people. And that muscle memory produces the semiconscious effect of being in the zone, hitting one shot after another.

You’ve had years and years of practice as a writer, so the writing muscle memory takes over and everything just flows. Yes, time has made the difference. Years of being a writer is writing the Tabula Rasa pieces, and I’m happily surprised by some things that go on in there. They wouldn’t be going on if I hadn’t been practicing for a long time. Now Farrar, Straus is going to publish Tabula Rasa, Volume I, in July 2023. The “Volume I” idea is that there be no end, that these books keep me unendingly alive!

I love that. It’s like A Thousand and One Nights. Exactly. What happened is, I’d been writing these things, and I was on a bike ride with a friend and I said, “You know there’s a paradox here. The whole goal of this project is that it never end, that I do one piece after another after another, with no end in sight. Yet, after you’ve written a certain number, you’re eager to publish them. So there’s a tension.” And my friend said, “There’s no problem at all. Just call it Volume I.”

Volume I of many to come! That’s the idea.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.