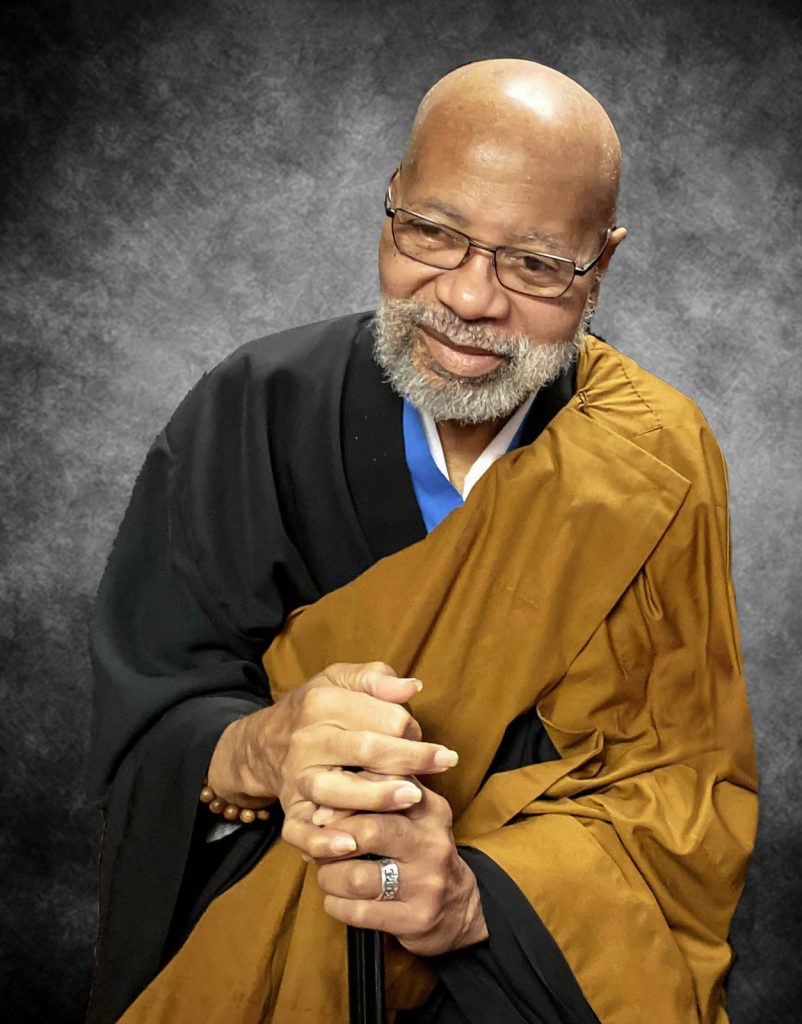

Jules Shuzen Harris Roshi, a Soto Zen priest who founded the Soji Zen Center in Lansdowne, Pennsylvania, died on May 8 at his home in Lansdowne, near Philadelphia. He was 83 and had suffered from “a prolonged period of complicated health issues,” according to a statement by John Ango Gruber Sensei, his dharma heir. A dharma successor of Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara, abbot of the Village Zendo in New York City, Shuzen Roshi was a member of the White Plum Asanga established by Taizan Maezumi Roshi and part of the Zen Peacemakers sangha founded by Bernie Tetsugen Glassman Roshi, as well as a member of the Soto Zen Buddhist Association and American Zen Teachers Association. He had been a Zen Buddhist practitioner for more than 40 years.

A dedicated and much-loved dharma teacher, Shuzen Roshi had, despite ill health, continued “showing up, week after week, to sit with us, chant with us, see students in interviews, and offer the teachings of the Dharma in both his words and his example,” Ango Sensei said.

“How did he do it?” Roshi Enkyo mused. In a message to Tricycle, she wrote:

Shuzen Roshi embodied the intimate teachings of Zen practice. He just naturally expressed the spirit and wisdom of Zen. We sat together, laughed together, and always, the Dharma emerged from his being. He manifested the joy of forms in Zen practice, as well as a longtime devotion to the disciplines of Japanese fencing and sword.

As a longtime psychotherapist and educator, Shuzen Roshi brought contemporary skills to his many years of Zen study. He dedicated his life to teaching Zen, to serving those who practiced with him, using all the tools he had honed in his many years of a life that truly expressed the compassion and wisdom of contemporary Zen practice. We will miss his intelligence and compassion—and his great heart!

Shuzen Roshi was born Jules Harris on December 6, 1939 in Chester, Pennsylvania. In a piece on gratitude posted on Tricycle’s website, he reflected on his family:

I am ever grateful to my paternal grandmother who taught me discipline and the meaning of hard work. I am filled with deep admiration for my father who became wiser as I grew older. I still hear his voice saying, “Watch what people do, not what they say.” His homily informs me daily that Zen is a verb.

Harris earned a doctorate in education from Columbia University, with a concentration in applied human development. As a psychotherapist, he “found creative ways to synthesize Western psychology and Zen to achieve dramatic results with his patients,” a biography on the Soji Center website states. As a black belt in Kendo (Japanese fencing) and a fourth-degree black belt in Iaido (drawing and cutting with a Samurai sword), he focused on the relationship between Zen and the martial arts, and founded swordsmanship schools in Albany, New York and Salt Lake City, Utah.

Shuzen Roshi had circled around Buddhism until he met Maezumi Roshi at a retreat in Vermont. Maezumi sent him to Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York, where he practiced under John Daido Loori Roshi. In 1998, he moved to Salt Lake City to study with Dennis Genpo Merzel Roshi, abbot of the Kanzeon Zen Center, receiving denkai (transmission of the precepts) from Genpo Roshi in May 2002.

After moving back East in 2004, Shuzen Roshi founded the Soji Zen Center in 2005 as a place, he said, “where people can go to slow down, meditate, and learn about the healing qualities of the mind. We all agree that training the body through exercise and diet is beneficial, but rarely in Western society do we focus on awakening the healing energies in our brain.” In the White Plum tradition, Soji combines elements of both Soto and Rinzai Zen, incorporating Soto meditation and Rinzai koan study.

In August 2006, Shuzen Roshi received hoshi—the rank of dharma holder—from Roshi Enkyo in a ceremony at the Grail, the Village Zendo’s summer retreat center in Cornwall-on-Hudson, New York. In 2007, he received shiho—full ordination as a sensei—from Roshi Enkyo. Then, in December 2019, he received inka (dharma transmission) from her, becoming a roshi and Roshi Enkyo’s second dharma heir.

In his book Zen Beyond Mindfulness: Using Buddhist and Modern Psychology for Transformational Practice, published in 2019, Shuzen Roshi outlined what he saw as the two main challenges facing American Buddhists today. One is “‘spiritual bypassing”—using what he called “pretend enlightenment”—to avoid dealing with psychological issues. The other is “settling for secularized forms of Buddhism or mindfulness that have lost touch with the deeper philosophical and ethical underpinnings” of the tradition. The solution he proposed blends rigorous meditation practice, intense study of Buddhist psychology, and a psychotherapeutic technique called “Mind-Body Bridging.” In an article for Tricycle, Shuzen Roshi explained why meditation practice alone could not resolve anger and psychological insight also was needed: “Meditation enables us to see the transparency of our anger, and this is a good start, but we can still remain blinded to the mechanics of our anger.”

Shuzen Roshi’s syncretic approach drew praise from Buddhists and mental health experts alike. “Dr. Harris clearly has a love affair with truth and the potentiality of human individual evolution,” observed Conrad Fischer, MD, program director of the Brookdale Hospital Medical Center. Gerry Shishin Wick Roshi, abbot of Great Mountain Zen Center in Berthoud, Colorado, called Zen Beyond Mindfulness “a significant contribution” to the dialogue between Buddhism and Western psychology that could help Zen students “dissolve emotional and psychological barriers to deepening their meditation practice.” Roshi Enkyo, in her foreword to the book, wrote, “I can’t think of a more qualified and appropriate person to take on the task of developing a contemporary technique for using mindfulness as a path of self-discovery and peace.” Publishers Weekly, an authoritative voice in the book world, called Zen Beyond Mindfulness “a refreshing alternative to the profusion of mindfulness literature.”

Roshi Shuzen was among the small group of Black Zen teachers in America today and one of the only roshis—a responsibility he took very seriously. He was a tireless worker and even as his health waned, he insisted on maintaining a full schedule. The day before he died, he held private meetings with thirteen students. “He never gave up,” Brenda Jinshin Waters, a member of the Soji board of directors, recalled. “He wanted to make the dharma available to everyone, regardless of race, color of skin, or socio-economic status.”

♦

For a look at Jules Shuzen Harris’s daily routine, see “A Day in the Dharma” in the Spring 2019 issue of Tricycle.

Correction: This article originally said that Jules Shuzen Harris moved to Salt Lake City in 1999, but he actually moved in 1998.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.