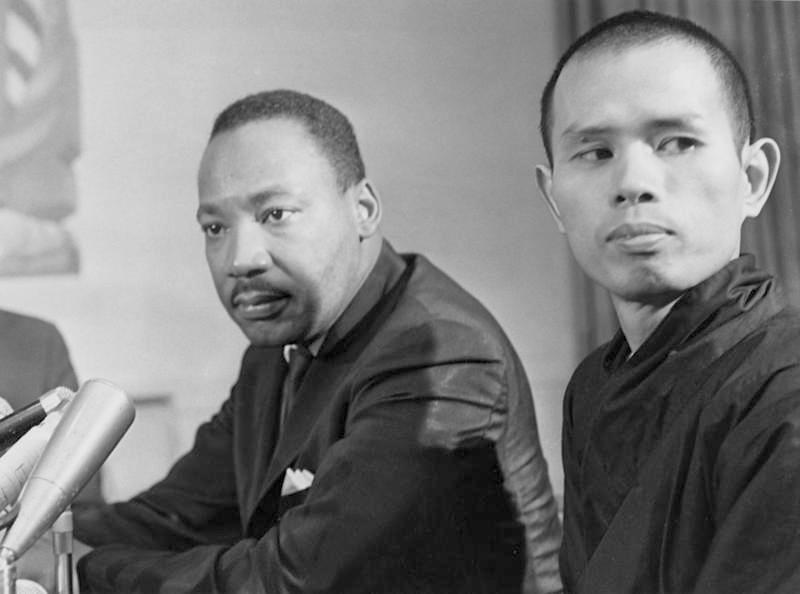

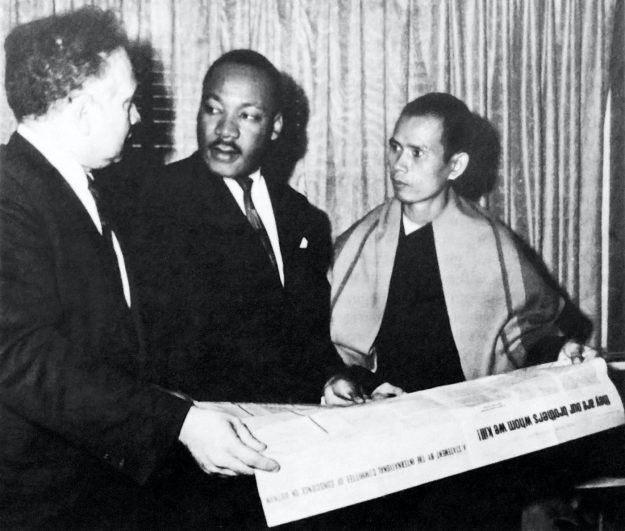

From “In Search of the Enemy of Man (addressed to (the Rev. Dr.) Martin Luther King” by Thich Nhat Hanh. In Nhat Hanh, Ho Huu Tuong, Tam Ich, Bui Giang, Pham Cong Thien. Dialogue. Saigon: La Boi, 1965. P. 11-20. Last month, the global Plum Village Community honored Nhat Hanh’s life and legacy as he became the 5th Patriarch of Từ Hiếu Temple and the founder of the Plum Village Sangha. Visit their website to learn more about this momentous occasion.

The following excerpt has been edited and adapted for grammar and clarity.

The self-burning of Vietnamese Buddhist monks in 1963 is somehow difficult for the Western Christian conscience to understand. The Press spoke then of [it as] suicide, but in essence, it is not [that]. It is not even a protest. What the monks said in the letters they left before burning themselves aimed only at alarming, at moving the hearts of the oppressors, and at calling the attention of the world to the suffering endured then by the Vietnamese. To burn oneself by fire is to prove that what one is saying is of the utmost importance. There is nothing more painful than burning oneself. To say something while experiencing this kind of pain is to say it with the utmost of courage, frankness, determination, and sincerity. During the ceremony of ordination, as practiced in the Mahayana tradition, the monk-candidate is required to burn one, or more, small spots on his body in taking the vow to observe the 250 rules of a bhikshu, to live the life of a monk, to attain enlightenment, and to devote his life to the salvation of all beings. One can, of course, say these things while sitting in a comfortable armchair; but when the words are uttered while kneeling before the community of sangha and experiencing this kind of pain, they will express all the seriousness of one’s heart and mind, and carry a much greater weight.

The Vietnamese monk, by burning himself, says with all his strength and determination that he can endure the greatest of sufferings to protect his people. But why does he have to burn himself to death? The difference between burning oneself and burning oneself to death is only a difference in degree, not in nature. A man who burns himself too much must die. The importance is not to take one’s life, but to burn. What he really aims at is the expression of his will and determination, not [his] death. In the Buddhist belief, life is not confined to a period of 60 or 80 or 100 years: life is eternal. Life is not confined to this body: life is universal. To express will by burning oneself, therefore, is not to commit an act of destruction but to perform an act of construction, i.e., to suffer and to die for the sake of one’s people. This is not suicide. Suicide is an act of self-destruction, having as [its] causes the following:

- lack of courage to live and to cope with difficulties

- defeat by life and loss of all hope

- desire for non-existence (abhava)

This self-destruction is considered by Buddhism as one of the most serious crimes. The monk who burns himself has lost neither courage nor hope; nor does he desire non-existence. On the contrary, he is very courageous and hopeful and aspires for something good in the future. He does not think that he is destroying himself; he believes in the good fruition of his act of self-sacrifice for the sake of others. Like the Buddha in one of his former lives—as told in a story of Jataka—who gave himself to a hungry lion which was about to devour her own cubs, the monk believes he is practicing the doctrine of highest compassion by sacrificing himself in order to call the attention of, and to seek help from, the people of the world.

I believe with all my heart that the monks who burned themselves did not aim at the death of the oppressors but only at a change in their policy. Their enemies are not man. They are intolerance, fanaticism, dictatorship, cupidity, hatred, and discrimination which lie within the heart of man. I also believe with all my being that the struggle for equality and freedom you lead in Birmingham, Alabama… is not aimed at the whites but only at intolerance, hatred, and discrimination. These are real enemies of man—not man himself. In our unfortunate father land, we are trying to yield desperately: do not kill man, even in man’s name. Please kill the real enemies of man which are present everywhere, in our very hearts and minds.

Now in the confrontation of the big powers occurring in our country, hundreds and perhaps thousands of Vietnamese peasants and children lose their lives every day, and our land is unmercifully and tragically torn by a war which is already twenty years old. I am sure that since you have been engaged in one of the hardest struggles for equality and human rights, you are among those who understand fully, and who share with all their hearts, the indescribable suffering of the Vietnamese people. The world’s greatest humanists would not remain silent. You yourself can not remain silent. America is said to have a strong religious foundation and spiritual leaders would not allow American political and economic doctrines to be deprived of the spiritual element. You cannot be silent since you have already been in action and you are in action because, in you, God is in action, too — to use Karl Barth’s expression. And Albert Schweitzer, with his stress on the reverence for life and Paul Tillich with his courage to be, and thus, to love. And Niebuhr. And Mackay. And Fletcher. And Donald Harrington. All these religious humanists, and many more, are not going to favor the existence of a shame such as the one mankind has to endure in Vietnam. Recently a young Buddhist monk named Thich Giac Thanh burned himself [on April 20, 1965, in Saigon] to call the attention of the world to the suffering endured by the Vietnamese, the suffering caused by this unnecessary war—and you know that war is never necessary. Another young Buddhist, a nun named Hue Thien, was about to sacrifice herself in the same way and with the same intent, but her will was not fulfilled because she did not have the time to strike a match before people saw and interfered. Nobody here wants the war. What is the war for, then? And whose war is this?

Yesterday, in a class meeting, a student of mine prayed: “Lord Buddha, help us to be alert to realize that we are not victims of each other. We are victims of our own ignorance and the ignorance of others. Help us to avoid engaging ourselves more in mutual slaughter because of the will of others to power and to predominance.” In writing to you, as a Buddhist, I profess my faith in Love, in Communion, and in the World’s Humanists whose thoughts and attitude should be the guide for all humankind in finding who is the real enemy of Man.

June 1, 1965

Nhat Hanh

Republished with permission of the Thich Nhat Hanh Foundation.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.