In his recent Huffington Post article “How the Nones Are Coming of Age,” Tricycle contributing editor Clark Strand notes a growing disenchantment with the spirituality craze that emerged as Americans turned away from religion in the decades following World War II. “The trend has peaked and people are looking for something more,” Strand recounts a friend telling him. “They don’t want to go back to the religion of their parents or grandparents, but they’ve wised up to the fact that they need something real to replace it, whether you call it a religion or not.”

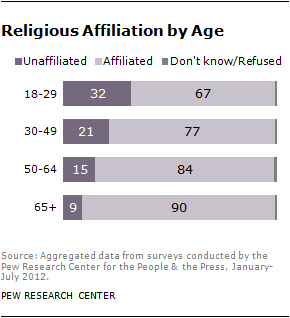

Academics refer to this religiously unaffiliated demographic as the “Nones”—those who responded to a Pew Poll about their current religion by choosing atheist, agnostic, or “nothing in particular.” The Nones inherited a suspicion of institutional religion from the countercultural generation of the 1960s, composed of freethinkers left to confront questions of death, divinity, and how to live a meaningful life often without the guidance of their parents’ religions. Taking notice of the hippies’ growing pains, spiritual hucksters rushed in to fill the void. “Religion had been deregulated by the culture,” Strand explains, “and newer, more generically spiritual models were rolling off the assembly line without being inspected by anyone but a marketing team.”

Such spiritual models endure, and they continue to treat the seeker like a retailer does his customer. Rather than freeing aspirants from self-occupation, spirituality often reinforces their yearning for a better version of themselves, as late Berkeley University sociologist Robert Bellah was wont to point out. When individual seekers come together, they do so on the basis of common beliefs or consumption patterns. Bellah used the term “lifestyle enclaves” to describe such informal groupings, and contrasted them with more deeply intertwined religious communities, which share history and tradition and foster relationships of mutually beneficial obligation. As an example, Strand invokes church communities’ “casserole ladies” who bring food to grieving members of the congregation. Loosely affiliated seekers are less likely to offer such support:

The person with whom you attend a yoga class and share an affinity for books by a particular Indian guru is a lot less likely to respond to distress in that homey casserole-cooking kind of way. Theoretically, of course, they could. But realistically they’re not organized to do it. It’s not automatic. You can’t count on it when times are tough. It’s the same people really, the ones who show up and the ones who don’t. But their spiritual communities are not the same.

Yet Strand does not necessarily call for a return to religion. What he welcomes, above all, is a renewed sense of commitment:

Those of us who’ve been redefining the American religious landscape for the past half-century are finally beginning to wake up a little and get…well, if not religious-not-spiritual, then at least real-not-flaky.

—Max Zahn, Editorial Assistant

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.