The Dalai Lama sent a letter to Sulak Sivaraksa last week to wish him a happy 80th birthday.

I remember our initial meeting during my first visit to Thailand more than 40 years ago when we were both younger men. Our paths have crossed many times since then. I continue to admire your work you have done to draw attention to the problems facing humanity and the courage with which you have offered suggestions for solving them…. I also appreciate the determination with which you have shown Buddhist teachings and practice to be relevant in the world today.

Relevance in the world today—this, above all else, has defined Sulak’s work for over half a century. While many Buddhist leaders understand this relevance in terms of integrating the Buddha’s teachings into day-to-day life, Sulak’s concern is how we might use the Buddha’s teachings to alleviate poverty, stem environmental devastation, and stop human rights abuses. For nearly half a century, this Siamese social philosopher, writer, and Buddhist activist has worked to solve these and other pressing dilemmas. He has traveled the world lecturing and publishing, mentored at home and abroad, participated in groundbreaking interreligious dialogues, and founded many organizations; one is the International Network of Engaged Buddhists, which has as its patrons the Dalai Lama, Thich Nhat Hanh, and the late Maha Gosananda. Sulak’s work is based largely upon a reinterpretation of the five Buddhist precepts and the Eightfold Path as not merely philosophical speculation, but as a blueprint for individuals and societies in the 21st century to cultivate more compassion, tolerance, and wisdom.

Sulak is not advocating a new understanding of Buddhism but rather an application of the Buddha’s teachings to modern socioeconomic and political dilemmas. To understand the teaching of the Buddha apart from its social dimension, Sulak will often say, is mistaken. He stresses the need for every individual to establish a strong foundation through the cultivation of mindfulness and awareness, but he does not let his students abide there for long. With an appreciation for interconnectedness born through meditative insight, Sulak wants spiritual practitioners to not only uproot their own suffering, but to realize how they may be participating in structures that perpetuate greed, anger, and ignorance within society. As much as it is the responsibility of the spiritual seeker to gain insight into his or her own path, it is also that person’s duty to dismantle structures of violence and suffering around them. Progress along one’s spiritual path and social reform, in Sulak’s vision, are inextricably linked.

Sulak is not advocating a new understanding of Buddhism but rather an application of the Buddha’s teachings to modern socioeconomic and political dilemmas. To understand the teaching of the Buddha apart from its social dimension, Sulak will often say, is mistaken. He stresses the need for every individual to establish a strong foundation through the cultivation of mindfulness and awareness, but he does not let his students abide there for long. With an appreciation for interconnectedness born through meditative insight, Sulak wants spiritual practitioners to not only uproot their own suffering, but to realize how they may be participating in structures that perpetuate greed, anger, and ignorance within society. As much as it is the responsibility of the spiritual seeker to gain insight into his or her own path, it is also that person’s duty to dismantle structures of violence and suffering around them. Progress along one’s spiritual path and social reform, in Sulak’s vision, are inextricably linked.

Sulak’s finger-wagging denunciations are not reserved for those people and governments advancing political and economic systems that perpetuate poverty, inequality, oppression, and violence. Sulak has also exposed the hypocrisy of Buddhist sanghas, groups, and organizations that waste time and precious resources on empty ritual, pompous ceremony, and indulging in materialism. And rarely does Sulak speak to Western dharma practitioners without giving the gentle reminder not to abuse retreat as escapism when there is social reform needed outside the meditation hut.

The razor-sharp critiques that Sulak makes use of in his over one hundred books in Thai and English and his firebrand speeches around the globe are a fundamental part of his Buddhist practice. Far from seeing such censure as ego-driven, Sulak feels he is being a true spiritual friend, kalyanamitta, to Buddhists and non-Buddhists alike. According to Sulak, critique and debate is one of the most expedient means to progress along the spiritual path, and using such methods to expose flaws and deviations from the path allows for their correction.

There is not a prominent “engaged Buddhist” who Sulak has not worked with, debated, or influenced. After seeing a photograph of the Dalai Lama holding a bottle of Coca-Cola, Sulak made sure upon their next meeting to inform the Tibetan leader how drinking Coke was sustaining structural violence inflicted by the soft-drink company. Last year, Sulak told his longtime friend and personal meditation teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, “A good friend tells you what you don’t want to hear,” and proceeded to encourage the Vietnamese teacher to have more dialogue with his students rather than just giving dharma talks.

There is not a prominent “engaged Buddhist” who Sulak has not worked with, debated, or influenced. After seeing a photograph of the Dalai Lama holding a bottle of Coca-Cola, Sulak made sure upon their next meeting to inform the Tibetan leader how drinking Coke was sustaining structural violence inflicted by the soft-drink company. Last year, Sulak told his longtime friend and personal meditation teacher Thich Nhat Hanh, “A good friend tells you what you don’t want to hear,” and proceeded to encourage the Vietnamese teacher to have more dialogue with his students rather than just giving dharma talks.

Sulak welcomes his own kalyanamitta calling him out whenever he is not walking his talk, though his sizeable ego often is the first to meet others’ pointed words. Still, Sulak will be first to say that being open to others’ criticisms is necessary for spiritual and social growth.

Kalyanamitta is woven through all of Sulak’s work, which has earned him two nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize (1993 and 1994). He was awarded the Right Livelihood Award in 1995 “for his vision, activism and spiritual commitment in the quest for a development process that is rooted in democracy, justice and cultural integrity,” and the Niwano Peace Prize in 2011.

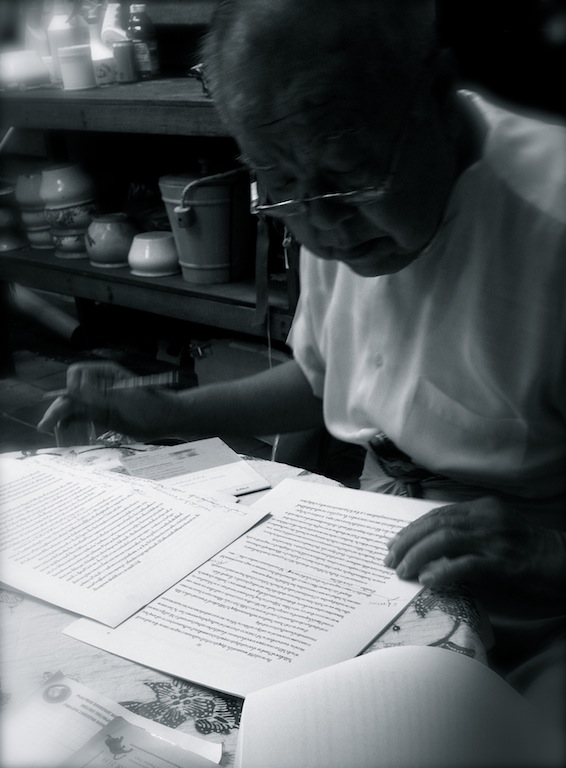

Sulak shows little signs of slowing down. When he is not hosting a steady stream of politicians, refugees, artists, and activists at his traditional home in the center of Bangkok, he is traveling abroad to attend conferences and give lectures. He writes daily and continues to publish.

Sulak’s penchant for exposing injustice, inequality, and systems of oppression, especially in his home country, has endangered his life, landed him in jail numerous times, and gotten him exiled from Thailand from 1976 to 1977 and again from 1991 to 1994. He has been repeatedly indicted for defaming the Thai monarchy, but has always won acquittals. Sulak maintains that he is being faithful to his brethren—even to the King—because, Sulak argues, “loyalty demands dissent.”

Photographs by Matteo Pistono.

Read Tricycle’s interview with Sulak from the summer 1992 issue.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.