In 2011, reporter Christine Toomey traveled to Dharamsala, India to cover the transfer of political power from the Dalai Lama to the newly elected prime minister of the Tibetan government-in-exile. There she met a former nun who had been imprisoned by Chinese authorities for five years. Their brief encounter haunted Toomey and sparked her interest in both Buddhism and the resilience and dedication of Buddhist nuns.

“In a world numbed by the amount of attention paid to violence, terrorism, and political and religious struggles, I find it personally refreshing to come across women whose lives are dedicated to nurturing the opposite,” Toomey writes in the introduction of In Search of Buddha’s Daughters: A Modern Journey Down Ancient Roads.

These initial experiences ultimately gave rise to Toomey’s ambitious and thoughtful book that explores both the solitude and the community of the monastic experience for women.

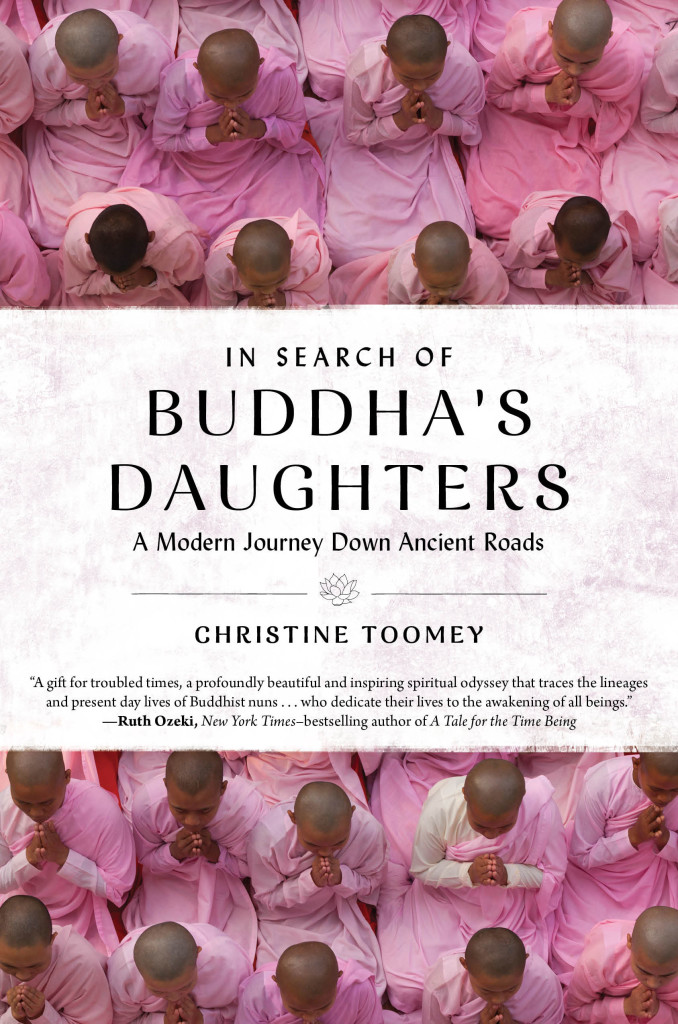

Traveling from Nepal and India to Burma and Japan and on to the U.S., the UK, and France, Toomey interviewed a wide range of women. Indeed, one of the most striking achievements of the book is the sheer number of voices contained within it. She profiles ethnic Buddhists and Western converts; nuns who had been married and raised children as well as women who took their vows at an early age. She speaks with “celebrities” such as Roshi Joan Halifax, as well as women who live more or less anonymously, all the while shedding light on the rich diversity of these nuns’ experiences. Toomey also meets with women who have for different reasons disrobed.

One of the most compelling stories in the book is that of Jakucho Setouchi, an energetic Zen nun now in her 90s. Setouchi first gained notoriety throughout Japan as the writer of several sexually explicit novels that won her both literary acclaim and exile from the male-dominated world of Japanese publishing in the 1960s. She has remained a public figure since ordaining in 1973, campaigning to end the death penalty and protesting the reactivation of the Fukushima nuclear plant—all while maintaining her vows.

Along with brief but valuable histories of Burma and Tibet, the book’s section on Japan is historically illuminating. Toomey explains that the first known ordained Buddhist in Japan was a young woman who founded the country’s first temple after returning from Korea in 590 C.E. This gave rise to a remarkable tradition of nuns and nunneries in Japan, though the numbers of both have dwindled more recently. At the same time, because the Japanese Zen tradition does not require celibacy of monastics (unlike Tibetan and Theravada Buddhism), many temples there were passed down from married male abbots to their sons, which also contributed to significant inequities between the sexes.

Not surprisingly, the different treatment of monks and nuns is a pervasive commonality across traditions. Toomey presents a careful consideration of the largest —whether “full ordination” should be available to women. The Buddha himself ordained Maha Pajapati, the aunt and stepmother who raised him and who would become the first woman renunciant. This original order of nuns in South and Southeast Asia, however, eventually died out. Women have been barred from full ordination since, due to a canonical rule that a nun can only be ordained by another nun. Although full ordination has now been restored in a few schools in countries such as Sri Lanka, the notion remains highly contentious in many of the places Toomey visited. Toomey writes that the Tibetan word for woman is lümen or kyemen—the literal meaning of which is “inferior being”—and reminds readers that the reality of sexism will persist even if full ordination of women in every Buddhist tradition becomes accepted.

Toomey paints vivid portraits of women who are emboldened in the face of gender discrimination, from the Jang Gonchoe festival at the Gelugpa nunnery Dolma Ling, where nuns have been engaging in the (previously male) art of debate since the mid-1990s, to the Redwoods of Aranya Bodhi, a Theravada hermitage in California where the American nun Ayya Tathaaloka is working with her fellow nuns to revive the tradition of bhikkhunis.

Toomey is a patient listener, aware from the start of the challenge of her role as reporter. “From a Buddhist perspective, the constant self-dramas in which most people wrap their lives are considered so ephemeral they have little inherent meaning,” she writes. “Everything I ask is inevitably informed by a Western perspective.” Notably, near the end of her travels and after hundreds of interviews, Toomey observes that her “way of asking questions . . . is changing,” as she becomes more of a student of Buddhism than a journalist on her beat.

While a triumph of the book is the vast array of individual stories it offers, the mass of material does present a challenge to the narrative structure, which at times reads more like a list than a deeper synthesis of either the tradition or the contemporary world by which these women are still bound. Toomey’s personal journey also remains alluded to more than explored, perhaps crystallizing the tension between her work as a journalist and her willingness to share the ways in which these exchanges have impacted her.

“A nun is someone who understands and is not understood,” a Venezuelan Zen nun living in Japan remembers her own teacher saying—which could likely be said of Toomey’s undertaking as well. Ultimately, this book reflects the enormous importance of listening to the lives, choices, and the courageous selflessness of Buddhist nuns. In this way, Toomey does provide readers with a deeper understanding of the international sangha of nuns, even if the influence of this work on her self is less clearly understood.

In Search of Buddha’s Daughters is available from The Experiment Publishing on March 22.

Related: Gender revisited: Are we there yet?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.