Buddhism’s history is often told through the grand monuments of great capitals and the famous pilgrimage sites that shaped its development across Asia. Yet some of the most intriguing chapters unfold far from these urban and much traversed centers. Such is the case in rural northeast Thailand’s Khorat Plateau, where winding rivers carve through the landscape, carrying with them not only water but also currents of faith, art, and community. This vivid world is described by Stephen A. Murphy in Buddhist Landscapes: Art and Archaeology of the Khorat Plateau, 7th to 11th Centuries (NUS, 2024). Drawing on nearly two decades of meticulous fieldwork, analysis, and interpretation, Murphy challenges conventional narratives that confine Buddhism’s vitality to imperial centers or established hubs of devotion. Instead, he reveals a richly textured monastic culture that flourished in the late first millennium across the river valleys and upland settlements of the Khorat Plateau—regions long overlooked by scholars and the public alike.

Buddhist Landscapes: Art and Archaeology of the Khorat Plateau, 7th to 11th Centuries

By Stephen A. Murphy

The University of Chicago © 2024, 288 pages, 95 color plates, 15 maps, 11 tables, $56.00, hardcover

The author’s focus on the Khorat Plateau stems from a deep interest in the interplay of art, archaeology, and religion in shaping lived Buddhist experience. Rather than viewing sacred sites and artworks as isolated relics, he situates them within the environmental and social contexts that gave rise to and sustained them. At the core of this approach is a recognition that Buddhism in the Khorat Plateau was not a static, uniform tradition but a dynamic tapestry woven from multiple Buddhist streams, local innovation, and shifting political realities.

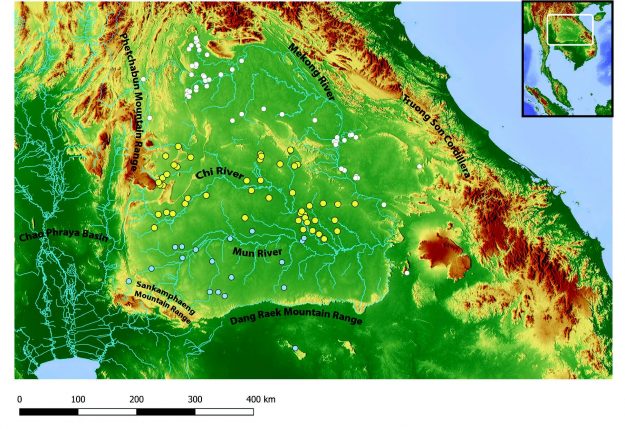

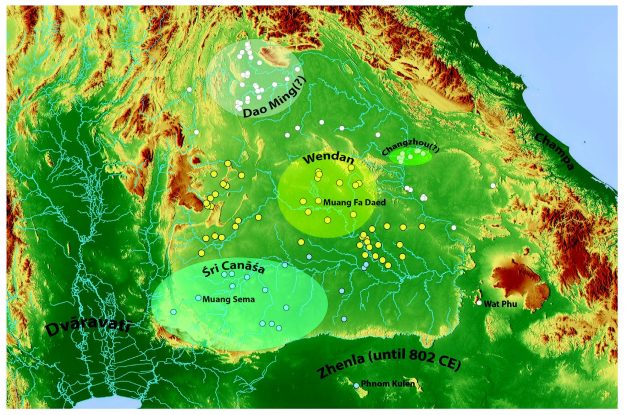

The Khorat Plateau occupies much of present-day northeast Thailand, bounded by the Mekong River to the north and east and the Dong Phaya Yen and Phetchabun mountain ranges to the west. Often perceived as peripheral to Thailand’s political and cultural centers, the region nonetheless played a pivotal role in the transmission and localization of Buddhism between the 7th and 11th centuries. Its river systems linked distant communities, facilitating the movement of people, goods, and ideas across the broader Mekong world. The Plateau emerges in Murphy’s study as a vital crossroads where diverse Buddhist traditions took root and evolved within distinct ecological and social settings.

Rivers as Waterways and Buddhist Pathways

One of the book’s most incisive frameworks is its organization around the three principal river systems of the region—the Chi, the Mun, and the Middle Mekong. These rivers are not mere geographic features but central actors in the story. They functioned as arteries of movement, exchange, and communication, linking disparate communities and facilitating the flow of religious ideas, artistic styles, and political influences.

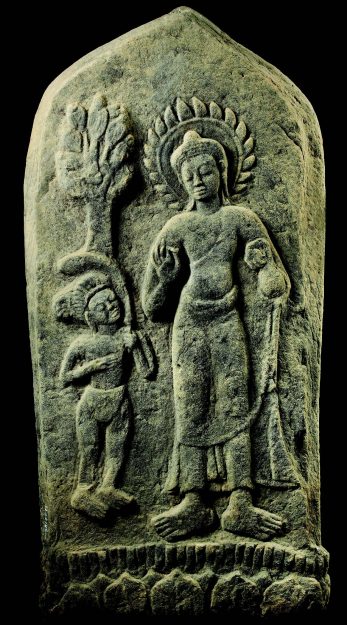

The Chi River system, for example, is home to the remarkable Mueang Fa Daet site, in Kalasin province, which Murphy interprets through the lens of the mandala—a concept often understood as a symbolic cosmogram but here used to illuminate the lived sacred geography of a Buddhist community. Mueang Fa Daet emerges as a vibrant religious center with workshops producing intricate and large boundary sema stones. These stones—carved markers for monastic sacred precincts often illustrated with scenes from the Buddha’s life or his previous births—embody a distinctive local Mon style that simultaneously reflects and diverges from better-known pre-Angkorian and Dvaravati models from neighboring Cambodia and central Thailand. This site exemplifies how local communities actively shaped Buddhist practice and artistic expression, embedding religious meaning in their environment and daily life.

Expanding outward, Murphy traces the wider upper and lower Chi basin. Here, the narrative complicates simple stories of cultural imposition or dominance. Instead, Murphy shows a nuanced exchange: Local artisans and patrons absorbed external influences selectively, adapting motifs and iconographies to fit indigenous tastes and devotional needs. This blending creates a distinctive regional style that challenges hierarchical views of cultural history and underscores the nature of Southeast Asia’s religious past.

Moving south and farther east, the Mun River basin and the Middle Mekong basin reflect the growing visibility of Khmer political power in the late first millennium CE. Yet this increasing influence did not erase local identities. Buddhist communities incorporated Khmer architectural and sculptural forms while maintaining continuity in ritual practice and belief. This highlights Buddhism’s adaptability and its capacity to mediate shifting power relations while preserving spiritual meaning.

The region also reveals a rich range of religious diversity and cultural connectivity. Murphy’s study of temple ruins and inscriptions uncovers multicultural communities where Avalokiteshvara, a bodhisattva associated with Mahayana Buddhism, appears alongside Buddha images. Artifacts attest to wide-ranging connections reaching west to the Bay of Bengal and beyond, firmly situating the Khorat Plateau within an expansive cosmopolitan Buddhist world. This regional integration invites readers to rethink the plateau not as a peripheral backwater but as an active participant in broader networks of faith and exchange.

A Pluralistic Buddhist Landscape

Central to Murphy’s analysis is the theme of religious pluralism. The Khorat Plateau was probably not a monolithic Theravada stronghold but a place where multiple Buddhist streams coexisted and intersected. This pluralism emerges clearly through the study of sema stones, sculptures, and inscriptions. The boundary stones are especially telling. They do more than mark monastic limits; they function as canvases of devotional expression and iconographic innovation, incorporating diverse Buddhist themes. Their unique forms and carvings attest to local creativity and the negotiation of identity in a region at the crossroads of cultural currents.

The concept of the mandala offers a powerful example of how Buddhist spatial and ritual organization articulated broader cosmological and social orders. The artistic and architectural developments at the sites provide a window into how religious meaning was embedded in community life and landscape.

Negotiation continues in the broader regional interactions across the plateau. Rather than one culture imposing its norms on another, Murphy documents a complex dialogue between the Zhenla and later Angkor civilizations of ancient Cambodia, the Dvaravati culture of central Thailand, and local traditions. In the upper and lower Chi basin, artisans adapted external styles creatively, resulting in a vibrant regional aesthetic. Similarly, in the Mun River region, Khmer political dominance influenced religious art and architecture, but local Buddhist communities maintained their own ritual identities. The Middle Mekong basin adds linguistic and religious diversity to this picture, with Mon inscriptions revealing a multilingual society deeply enmeshed in transregional Buddhist networks.

The book’s final chapter emphasizes this dialogic process as a defining feature of the Khorat Plateau’s Buddhist landscapes. The author argues that cultural exchange was never simply one-sided or coercive but involved negotiation, adaptation, and blending. Even the rise of important regional centers should be understood as reconfigurations rather than replacements of earlier local traditions.

Bringing the Past to Life through Visual Evidence

Beyond text, Murphy’s rich visual documentation plays an indispensable role in his argument. With more than one hundred illustrations—including many intricately carved sema stones, detailed images of Buddhist sculptures, tables, and maps—he invites readers into a direct encounter with the material traces of Buddhism on the Khorat Plateau. These images do more than support the narrative; they serve as evidence of a vibrant religious culture shaped by artisans, patrons, and communities. The maps, in particular, orient readers who may be unfamiliar with the geography of northeast Thailand, allowing them to trace the paths of rivers and the distribution of sacred sites that defined the spiritual landscape.

This visual dimension is crucial to understanding the materiality of faith—the way Buddhist ideas were made tangible in stone and metal, how sacred space was demarcated and experienced, and how communities inscribed their identities on the land.

Future Directions and Remaining Questions

While Murphy’s work breaks important new ground, it also highlights areas ripe for further exploration. His focus is primarily on monastic and elite material culture, leaving the experiences of lay practitioners less visible. The everyday devotional lives of ordinary people—how they engaged with temples, icons, and rituals—remain a fertile field for future research.

Another area for future inquiry is the relationship between Buddhist and non-Buddhist traditions in the region. The author acknowledges the presence of Brahmanical imagery and rituals and one can even note instances of religious syncretism, but these themes are only lightly sketched. Given the close intertwining of Hindu and Buddhist iconography in many Southeast Asian contexts, a deeper exploration of these interconnections would further enrich our understanding of religious life on the Khorat Plateau.

Additionally, while Murphy’s use of the mandala model to explain political and religious organization is helpful, his application occasionally risks oversimplifying the diversity of local polities. The mandala framework—adapted from Indic cosmological and political ideas—has often been used in Southeast Asian studies to characterize fluid and overlapping spheres of influence rather than fixed territorial boundaries. Yet, in its original Buddhist and royal contexts, the mandala was anything but decentralized: It emphasized the central authority of the king or the Buddha at its core. A more critical engagement with these tensions might have opened space for alternative ways of understanding sovereignty and sacred space in the Khorat Plateau.

Despite these avenues for future inquiry, Buddhist Landscapes stands as a landmark achievement. It expands our understanding of early Southeast Asian Buddhism’s geographic spread and internal diversity, revealing a world where faith was inseparable from landscape and local culture. This book invites readers to see Buddhism not as a fixed tradition rooted only in famous temples and capitals but as a dynamic, evolving religion shaped by communities living in complex environments.

For readers seeking a deeper, more textured understanding of Buddhism’s past beyond familiar narratives, Murphy’s book offers a compelling journey into a lesser-known Buddhist world. Here, the rivers of the Khorat Plateau carry stories of devotion, artistic innovation, and cultural exchange—reminding us that the dharma flows as surely as the waters that nourish the land.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.