At a new exhibit inside the Japanese American Museum in Los Angeles, a beautiful wooden altar dedicated to Shinto deity of war Hachiman Daimyojin sits next to two hand-carved wood panels, one engraved with psalms and the other with a Buddhist devotional phrase. Built from scrap material, the altar originally occupied the Judo dojo at Tule Lake Segregation Center, an internment camp in Newell, California, just south of the Oregon border. Written on the dojo, and showcased in the exhibit, are the words “ju yoku go o seisu,” or “softness subdues hardness.”

The altar is just one of many moving artifacts on display at Sutra and Bible: Faith and the Japanese American World War II Incarceration, an exhibit curated by Duncan Ryuken Williams and Emily Anderson. On view until November 27, 2022, the show carefully guides visitors through the experience of Japanese Americans before, during, and after the forced removal and mass incarceration that occured at the issuance of President Roosevelt’s 1942 Executive order 9066. Showcasing altars, statues, prayer books, and more, the exhibit reminds us of the power that religion, faith, ritual, and community carry in all circumstances, but especially in the most trying of times. At this heartbreaking moment that we must keep remembering, religion—both Buddhism and Christianity—provided what was needed above all else: resilience.

After Pearl Harbor, Japanese Americans were forced to hide or destroy any personal items that were made in Japan or contained Japanese script for fear of being seen as a threat or as disloyal. When the over 120,000 people were incarcerated in internment camps, they weren’t allowed to bring any religious artifacts with them. Buddhist and Christian laypeople and priests had to rely on memories of scripture and formed study groups in barracks to practice ritual and create community. Some made their own religious relics by hand, taking materials like wood from mess hall crates to create objects of worship, or even rocks from the ground, as evidenced by the ink-inscribed Heart Mountain Sutra Stones.

In 1956, a man named Bill Higgins, who was an employee of the Bureau of Reclamation, unearthed a metal drum that had been buried beneath the cemetery at the Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming. It contained two thousand ink–inscribed stones. The meaning of these stones remained unknown until 2001, when scholars revealed that the characters together formed the first six volumes of the Lotus Sutra. Since the Nichiren lineage of Buddhism is most closely associated with the Lotus Sutra, scholars suspect that Reverend Nichikan Murakita, who was the only ordained Nichiren priest incarcerated at Heart Mountain and also a master calligrapher, was the person responsible for the stones. Hundreds of the Heart Mountain Sutra stones went missing in the years since they were discovered, but the Japanese American National Museum now holds the largest collection, and they’re on display in this exhibit.

Copying sutras is a form of meditation and a devotional Buddhist practice dating back to late seventh century Japan. The Lotus Sutra itself explains the importance of copying down words of sacred text as a form of practice. The Heart Mountain Sutra Stones represent the enduring power of this practice, which endowed thousands with resilience when they needed it most.

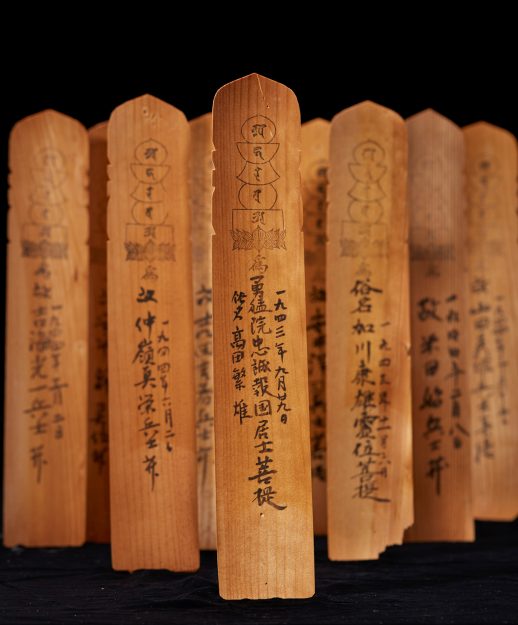

Elsewhere in the exhibit stand tall wood toba, or Buddhist memorial tablets, with names of Nisei soldiers who died at war. Reverend Mitsumyo Tottori of the Hale’iwa Shingon Mission in Hawaii, who was one of the only Issei Buddhist priests not arrested and interned, handwrote around 420 toba and placed them within his temple to make sure that each soldier who died in battle was properly honored. Just nearby are photographs of memorial services conducted in concentration camps by Christian clergy to mourn and provide religious ceremony for lives lost both in combat and at the internment camps.

Beneath a plexiglass display, surrounded by well-worn rosaries, a prayer for soldiers at war:

O God, I beseech Thee, watch over the souls of those who are exposed to the horrors of the war, and to the spiritual dangers peculiar to the soldier’s life. Give them such strong faith that no human respect may ever lead them to deny it, or fear to practice it. Do Thou, by Thy grace, fortify them against the contagion of bad example, that, being preserved from vice, and serving Thee faithfully , they may be ready to mee death whenever it may happen. Through Christ Our Lord. Amen.

The exhibit also features scenes where ritual bestowed a sense of normalcy for prisoners: rhythm in a time of chaos and purpose in the face of senseless imprisonment and dehumanizing conditions. One large, colorful photograph captures a gathering of women and children dressed in beautiful kimonos. Next to it is a drum framed in a plexiglas case. The photograph and drum were used for the Obon ceremony held at Honouliuli Internment Camp in Hawaii on August 15, 1942. As curator Duncan Ryuken Williams said in his virtual exhibit opening remarks, “Resilience is the practice of skillfully adapting to a changeable and sometimes distressing world grounding oneself in enduring truths.”

Or, “softness subdues hardness.” At a time when the world is still at war, Sutra and Bible reminds us how religion and faith—Buddhist, Christian, or otherwise—connect people and fortify them to endure turmoil, pain, and uncertainty. It shows us there is compassion in community, and resilience in yearning for something beyond. At the same time, it shows us the freedom in being present and awake to the world as it stands. In faith and religion, the path is no longer separate from our footsteps, and we can tap into the wisdom of presence—even in our darkest hours.

♦

Join the August 13 event, “For Every Generation: Recovering and Sharing Family Histories,” virtually or in-person to hear Dr. Gail Y. Okawa, Mitch Homma, Elizabeth Nishiura, and Laura Dominguez-Yo talk about the efforts they made to preserve their own family histories, including artifacts that are part of Sutra and Bible. Learn more here.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.