Organizing an art show around a geographic region or ethnic group is treacherous: it can easily result in a grouping of works that otherwise have nothing in common or, worse, reinforce unwanted stereotypes. Transcending Tibet—presented by the Trace Foundation in partnership with Arthub Asia—is alert to these dangers and does a good job of avoiding most of them.

Transcending Tibet

Through April 12, 2015

Rogue Space, New York

Curators David Quadrio and Paola Vanzo accomplished this by commissioning all new pieces for the show. They asked 26 Tibetan artists—living both in and outside Tibet—and four non-Tibetan artists influenced by Tibetan culture to respond to the question “What does it mean to be Tibetan today?” On view at Rogue Space in Chelsea are 30 different answers.

For both the curators and the artists, “Transcending Tibet” means transcending the image of Tibet as both a mysterious Shangri-La (an image embedded in the Western imagination since the time of Marco Polo and energetically promoted by Chinese tourist boards) and as a political cause (for groups promoting human rights and democratic freedoms in the Tibetan region, since 1951 a part of the People’s Republic of China [PRC]).

Transcending Tibet also means, in many cases, transcending tradition. Most of the artists included in the exhibition struggle to find a balance between preserving Tibetan culture (which is also primarily a Buddhist culture) and addressing the contemporary realities—such as modernization, urbanization, and the secularization of Tibetan culture—of those living in Tibet and its diaspora.

Many of these artists, including Rabkar Wangchuk and Tulku Jamyang, update the forms of traditional Tibetan Buddhist thangka paintings, prayer scrolls, and folio scriptures. Others adopt the tropes of Western Pop Art, as in the case of TseKal, or Communist Socialist Realism, as does Pempa (who, like many Tibetans, uses only one name). Although some Tibetan contemporary artists produce abstract paintings, and while much Tibetan traditional art, from sand mandalas to textiles, features reductive images or geometric designs, the show does not include any nonobjective art. Even Pema Rinzin, an artist known for abstraction, is represented here by a painting of stylized, but recognizable antelopes. The omission constitutes one of the show’s few missteps—some examples of non-illustrational art would have helped balance its occasionally didactic tone.

Of the artists employing traditional Buddhist imagery, some retain its original meaning in works meant to express their faith, while others repurpose it to convey a social or political message. In the former category is Livia Liverani, an Italian who has studied classic Tibetan sacred art. Isolating visual elements from traditional thangka paintings, she presents them as delicate appliqued and painted images. Her work for this exhibition depicts the blue, three-faced, six-armed Vajrayana deity Guyasmaja engaging in sexual intercourse with his consort. Representing the union of wisdom and compassion necessary for full enlightenment, the couple—flanked by flowering plants cut from Japanese textiles—floats on a pure orange ground.

Other devotional artworks include Puntsok Tsering’s calligraphy spelling out the words for “butter lamp”—a ritual object used to make the traditional offering of light—and Chinese artist Lu Yang’s digital animation Wrathful King Kong Core, which advances the practice of analytical meditation by explaining scientifically how the brain can become wired for anger (and rewired through mindfulness). More ambiguous is Jhamsang’s depiction of the Buddha of long life, Ushnishavijaya. Trained as a thangka painter, Jhamsang here employs a traditional technique of fine black lines on a gold ground but presents the deity as a robot, invoking the language of anime to indicate the goddess’s superhuman powers—or perhaps comment on contemporary society’s devotion to technology.

Tashi Norbu’s Circle of Khataks suggests the performance of “Tibetanness.”

Tashi Norbu’s Circle of Khataks suggests the performance of “Tibetanness.”

Buddhist imagery is also used to address political, environmental, and social issues. Nyima Dhondup’s Tibetan Map includes a calligraphic passage extolling the Dalai Lama’s Middle Way political philosophy. Part of the text reads, “The Middle Way policy is a mutually beneficial policy based on the principles of justice, compassion, nonviolence, friendship, and in the spirit of reconciliation for the well-being of entire humanity. It does not envisage victory for one self and defeat for others.” The Middle Way policy is itself an example of how Buddhism permeates every aspect of Tibetan life, including politics.

Individual and collective trauma haunt Sonam Dolma Brauen’s mandala made from a stack of folded Tibetan monks’ robes, which shelters in its center nine tsa tsa—offerings made from clay and the ashes of the dead—in the shape of stupas. The tsa tsa mold used to make them was carried out of Tibet by Brauen’s family in a journey that took the life of her sister. Trauma is also addressed in Nortse’s Fragments, which combines an ink-jet print of a damaged antique bronze Buddha with real broken glass, and in Rigdol’s Wrathful Dance, a brocade and paper collage of a Buddha in flames that brings to mind the Tibetans who have self-immolated in protest of Chinese Communist Party rule.

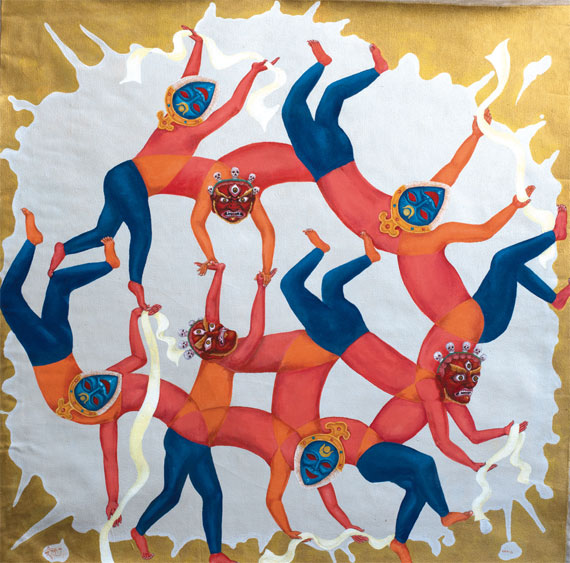

Other works address the complexities of daily life for Tibetans both in the PRC and in diaspora. Tashi Phuntsok’s quiltlike painting of rows of houses surrounded by protective prayer flags suggests the simultaneous claustrophobia and reassurance of community. Tserang Dhundrup’s photoreal painting of a Khampa wearing traditional hair ornaments but also a Nike puffer and holding an iPhone sums up the contradictions of modern urban existence in Lhasa. That this life is attended by rigid controls on religious and political activities on the one hand and the promotion of Tibetan culture as tourist attraction on the other is suggested by Tashi Norbu’s wonderful composition in which Matisse-like acrobats perform a complicated gymnastic routine. Each wears a traditional mask, suggesting that the performance of “Tibetanness” comes at the expense of individual expression.

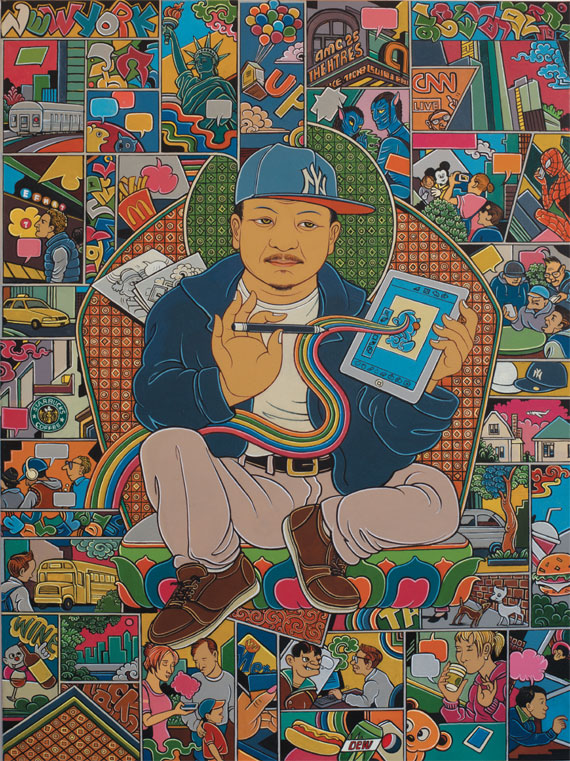

Sodhon captures the immigrant experience in New Life.

Sodhon captures the immigrant experience in New Life.

Censorship and self-censorship also lie at the heart of Meditator Beware, a self-portrait by Benchung, a Lhasa native. The painting depicts the artist as a yogi who dons a meditation belt and mala, but also, oddly, a camouflage pattern t-shirt and a diaper. A swarm of words—including the name of Chinese dissident Ai Wei Wei and of websites like Google and Facebook, which are blocked in the PRC—forms a golden halo around his head. According to a statement by the artist, the Band-Aid on the figure’s arm symbolizes the covering up of injury, and the diaper the loss of autonomy under a parental Communist state.

Sodhon captures the immigrant experience in New Life, a wonderful, comic strip–like painting reminiscent of the work of Chris Ware and Adrian Tomine. Shown drawing on an iPad, the artist occupies the center of the canvas and is surrounded by beautifully observed vignettes of New York City life. In each vignette, the word bubbles are left blank, perhaps because the work’s protagonist still finds English a confusing babble.

Not to be missed are two extraordinary paintings by Tseren Dolma. The first, titled Desire, depicts a tiny woman with a big head engaged in eating a globe while holding on to the three poisons—ignorance, attachment, and hatred embodied as a pig, a rooster, and a snake. In the second painting, Underworld, a dark opening in a green landscape reveals a pair of cheerful dancing skeletons and a flock of vultures feasting on bones. Rendered in an exuberant, naïve style, Dolma’s canvases are powerful, original, and, while nodding to traditional iconography, deeply personal. They exemplify the individualism that marks all of the works here, and they walk away with the show.

Images courtesy Trace Foundation

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.