Motivated by the unknown, Tibetan-Swiss multidisciplinary artist YESH speaks to the current moment through lyrical incantations of the past, drawing on Buddhist teachings, rituals, and practices of devotion in a refreshing and ever-evolving storytelling modality.

Known for her genre-defying sound and wide vocal range, YESH glides effortlessly between low and high pop-electronic frequencies. YESH’s uncanny ability to flip downtrodden and cutting lines into vibrant, reimagined futures is testament to her uniquely fluid manner of artistic expression as influenced by her diasporic identity and her time spent between New York City and Switzerland, where she was born and raised. Personally and professionally, YESH holds trust and intuition as the bedrock of her practice. Drawing across generations of knowledge systems and landscapes of personal and collective histories, her work concerns, but is not beholden to, the topics of identity, belonging, grief, memory, and the reclamation that follows.

Thus far, YESH has released several singles independently as well as a debut EP, hour 2147, which was released with Pique Project in 2020. Inspired by the esoteric tradition of Tantra, YESH collaborated with multidisciplinary artist, painter, and composer Alex Asher Daniel on the single Dakini off Daniel’s 2021 album Book of Spells. Earlier this year, for the April 2023 Issue of The Brooklyn Rail, YESH dropped her single Lhamo, produced by Yanling, with lyrics based on a Tibetan song her mom used to sing to her. “I threw a stone at the nut tree, 20 nuts fell on the ground, I only ate one, 19 I offered to the deities.”

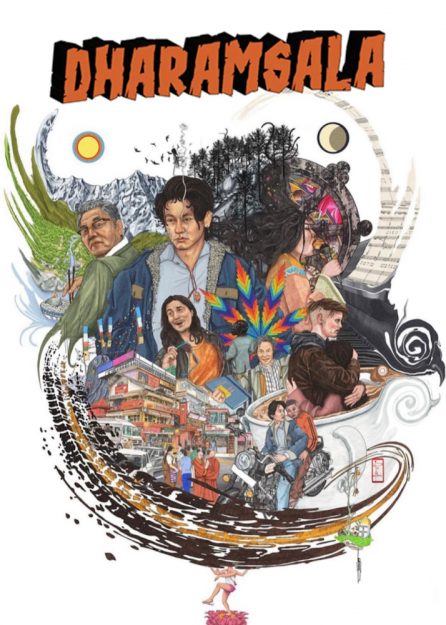

And as 2023 winds towards its end, YESH’s transformative and uniquely narrative art practice only continues to expand. Recently, YESH sat down with Tricycle to discuss her childhood introduction to music, her work with the collective XENOMETOK on their bardo-inspired 49 days project, and her recent casting in the upcoming Tibetan indie film Dharamsala.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you tell us about your early life? My parents were one of the first Tibetan refugees to find exile in Switzerland. They settled down in the Pestalozzi Children’s Village, a nonprofit organization that provides a home for war-affected families from all over the world. It was founded in 1945 in Trogen in Appenzell Ausserrhoden. I grew up in this children’s village in a house with 15 other kids and with many others from all over the world. The village is surrounded by hills, cows, and sheep.

How did you first become interested in music? The strong presence of cultural exchange throughout my early childhood significantly shaped my voice and my artistic work. Music and dance were a part of my daily life.

My comrades and I created our own dance group and we would perform at local gatherings. We also had a choir, where we learned songs in different languages. The mother of the Cambodian house taught us how to dance to Cambodian music, the mother of the Ethiopian house taught us to dance Ethiopian. Through that I learned their customs and traditions as well. Since it was a refugee village, living in the diaspora is what connected us and what allowed us to feel the solidarity of belonging, having a home and a community. And music was just a huge part of our everyday communication.

Later, as an adult, I lost the connection to singing for a while until I started longing for a place where I could create freely, where I could express myself and set my own beat. About ten years ago, I suddenly knew I needed to set my focus on music and singing.

Are there any teachers or moments in your life that have molded you into who you are today as an artist and how you approach your creative practice? I can’t really think of one particular teacher or moment. I like to think of life as a teacher in general. Some moments are like mini classes and the people you meet are your classmates. In the best case the whole world is a classroom and everything and everyone is interconnected and in constant motion. Just like music! That’s why I love collaborating with producers, instrumentalists and other artists. Creating together, flowing together–listening and observing what occurs when you create music in a certain time and space makes me feel present and alive.

And then I also think, in contrast to life, death and losing loved ones is kind of a teacher. Letting go and coping with grief has shaped me as a person and also my creative practice. During a period of grief I came to understand that the breath of life and emotion held in every voice and in every moment is impermanent. The life philosophy of Buddhism of course helped me a lot to understand this lesson.

“During a period of grief I came to understand that the breath of life and emotion held in every voice and in every moment is impermanent.”

Could you tell me a bit about your collective XENOMETOK and the inspiration behind your performance piece, 49 days? XENOMETOK is a transdisciplinary collective and collaboration between artist Valentina Demicheli, Tibetan activist Paelden Tamnyen, and myself. Our first theater piece was 49 days. It’s a one-hour multimedia performance, orchestrated by electronic and experimental music, singing, traditional Tibetan drums, the Repa Dance, and moving images. We work thematically in the field of tension between reappropriation, Asian foreign perception, and self-perception. 49 days has to do with the period following death. The bardo is a between-state (marking the passage from death to rebirth, as well as the journey from birth to death).

49 days bridges the individual and collective paths of three deceased sisters. The three sisters are caught in the tension between longing for a new world and an apparent afterlife. In this in-between, they experience memories of heritage and Tibetan rituals. Through this performance, we are creating a space outside of time, like the in-between of the bardo. Our next performance with this piece is in Brussels at the Kaaitheater in April 2024.

How do you engage with these centuries-old rituals using contemporary performance styles? With old rituals, it is a bit like when you dismantle old clothes and playfully put together the patterns again in a different way. A learning by doing situation. For example, the Repa dance: we were able to borrow the drums from the Tibetan dance group in Switzerland and a friend introduced us to a Tibetan woman who studied at the Tibetan Institute of Performing Arts and taught us the dance. The engagement with the drums was physically exhausting because the drums are so heavy. And that led to the fact that we danced with the drums in the hourly performance for only about twelve minutes.

Creating 49 days was a long process. We started off with having long conversations over Zoom, imagining a tale-like narrative. In a second step, we brought in an amazingly talented crew and cast of a choreographer, a light technician, a set designer, visual artists, and dancers that made the piece at the end what it is. We were reacting organically to a situation. On one hand, our fluid improvisational approach welcomed uncertainty and allowed the piece to adapt in different situations, and on the other hand, our everyday collaborative practice became like a repetitive ritual that we could always return to. This happened very naturally, just like how we grew up with Tibetan rituals when we were kids.

How did you find a balance when combining traditional Tibetan musical techniques and digital, audio-engineered sounds? It comes very naturally to me. It’s like reinventing and enhancing an ancient culture. I’m interested in storytelling and the use of music and performance for self-expression, for identity formation. It’s also part of a cultural interaction. I feel my role as a Tibetan-Swiss woman, who was raised by a Tibetan-born mother and is now living in diaspora, is to keep Tibet relevant. And I’m using music and performance in a liberating way. I like to see my artistry or my voice as an extension of my maternal lineage.

If I were to just do traditional Tibetan music I think I couldn’t add anything that I’m interested in. I think I would like to learn more from the traditional Tibetan music/musicians and create my own voice/language that speaks to me and the next generation.

“I feel my role as a Tibetan-Swiss woman, who was raised by a Tibetan-born mother and is now living in diaspora, is to keep Tibet relevant.”

I think whether it’s in making movies, creating art or music, “our” own narrative needs to be told in order to change the perception of Tibet. There’s so much power in storytelling. But the challenging part about it is relaying that what I have to say is enough. Like, my voice is enough. Getting to this point has a lot to do with confidence.

How has performing and creating 49 days deepened your own spiritual practice? My spiritual practice influences my creative practice and vice versa. I realize this especially when I’m singing—it feels like I’m dissolving with the surroundings and becoming lost in my voice and the space. When you dissolve with the room, your ego goes, the I is gone, and it becomes more like we or us.

How do you get yourself into the present moment before you perform? What does this process look like for you? I close my eyes, I focus on the center of my body, breathe in and breathe out, and I envision the ocean in slow motion and how the water takes over myself.

In addition to being a singer, songwriter, dancer, and performer, you were recently cast in the indie film Dharamsala. Can you tell me more about the film and how you navigate these various art forms? I think they don’t contradict each other. More so I feel like they elevate each other. You learn from each situation and from working with different people. I’m not a singer alone—I would not be a singer if I did not have an audience. I love creating and collaborating with people. All these experiences and art forms are becoming part of the storytelling. I would like to amplify the voices and turn up the volume for Tibetan women. I hope that we can continue building a strong creative foundation for the next generation to tell their stories through various forms of media.

I have a minor part in Tenzin Dazel’s Dharamsala, which is her first feature film and focuses on Dharamsala, a small town on the edge of the Indian Himalayas that has been the heart of the Tibetan exile world for six decades. It is the residence of the Dalai Lama, the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile, and home to many other important Tibetan cultural and religious institutions. But along its narrow shop-lined lanes and in the houses clinging to the hillsides, it is also where the hopes, aspirations, and pain of Tibetans living far from their homeland are lived, and where the drama of ordinary human lives unfolds.

Since it was my first appearance in a movie it was an honor to work with such a talented Tibetan and Indian cast and crew, and to slip into a role, a character that is different from my stage persona and myself, was very inspiring and liberating.

Are there any other projects you’re working on? Is there anything else you would like to add? I’m currently working on my debut album with Asma Maroof as the executive producer. I’m very excited about it because it’s about everything that matters to me and it feels like a stepping stone towards change.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.