The Buddha is the meditator par excellence. When people think of meditation, they often picture the Buddha, his hands in what is called the dhyanamudra, the “meditation pose,” right palm resting on the left palm, thumbs touching to form a circle. And yet more common is a different pose, left hand turned upward and resting in his lap, right hand extended over his knee. It is called bhumisparsha in Sanskrit, literally “touching the earth.”

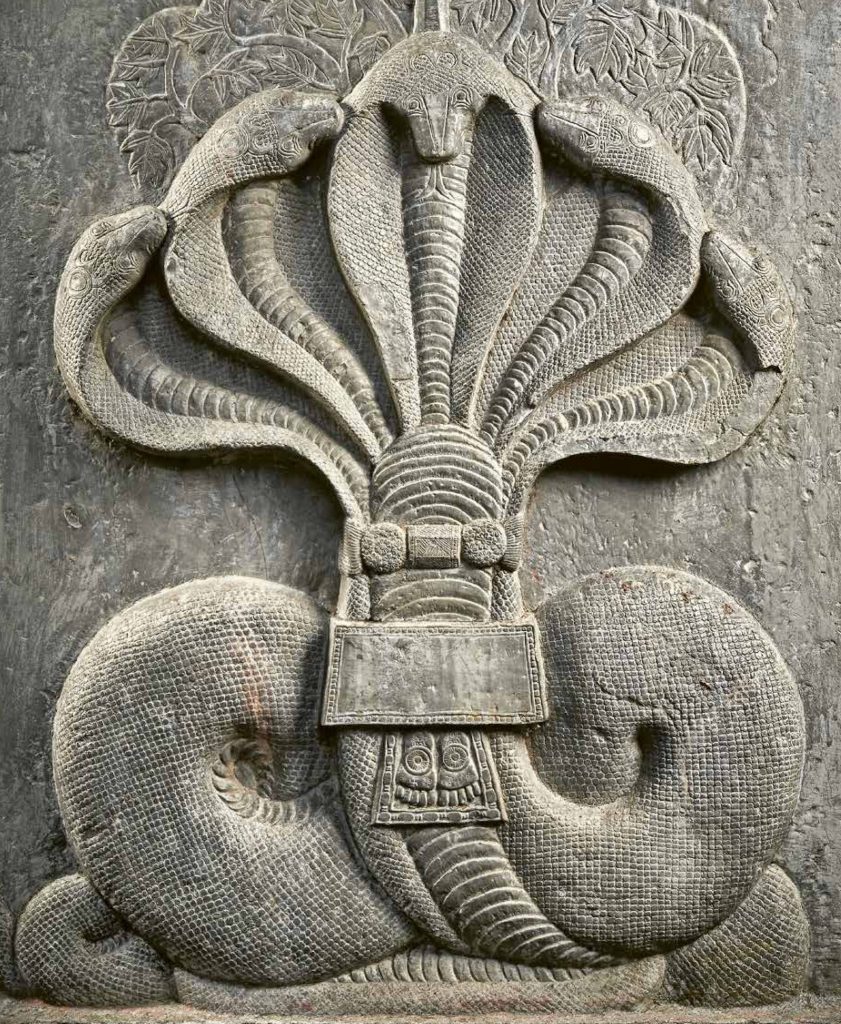

A fabulous exhibition of early Indian Buddhist art opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York on July 21, continuing until November 13, featuring masterpieces from 200 BCE to 400 CE, a golden age of Buddhist art. It is called “Tree & Serpent. Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE – 400 CE.” The signature piece shows, as one might expect, a tree and a serpent, indeed a magnificent serpent, with five hooded heads. The Buddha, however, is nowhere to be seen. Unless, that is, one knows how to look. Unless one knows the story. Because if you look closely, you see a small rectangle on the coils of the giant snake, and below the rectangle, you see what appear to be a pair of footprints. The footprints are the footprints of the Buddha; the seat is where he is seated in meditation. The Buddha, however, is not there.

This is one of many representations of the Buddha in early Indian Buddhist art in which the Buddha himself is not represented. Instead, there is a seat, a wheel, a stupa, or a pair of footprints. Art historians call these works “aniconic.” It is not that other humans, gods, and animals are not depicted in these works. Only the Buddha is absent. Art historians have been arguing for more than a century about why this is the case. No prohibitions of drawing, painting, or sculpting the Buddha have been found in the Buddhist canon. And in later centuries, as we know, statues of the Buddha began to appear in both northwest India and in central India. Striking examples of both aniconic and iconic works are found throughout the exhibition.

The exhibition makes clear that we cannot understand the Buddha until we see what surrounds him.

And so the Buddha is absent in this piece, at least in the form that is familiar to us; this piece is clearly aniconic. But why the giant serpent? For this, you must know the story. After he achieved enlightenment, the Buddha spent seven weeks—forty-nine days, the same period as that between death and rebirth—in the vicinity of the Bodhi tree. Not eating, not sleeping, not speaking, reliving the experience of enlightenment, trying to decide whether he should teach. Each of those seven weeks is marked by a particular event at a particular place; those places are now shrines at Bodhgaya. During the third week, there was a horrific rainstorm. A huge serpent, the guardian of a nearby tree, emerged from a lake, wrapped himself around the Buddha, and spread his hood, providing shelter from the storm. This is the event depicted in the sculpture.

Such stories abound in the works on display in “Tree and Serpent,” suggesting that early in the history of Buddhism in India, scenes from the life of the Buddha could be carved in stone, without textual description, and often without the Buddha himself, and be still recognized by the faithful. Ordinary people knew these stories, and if they didn’t, there was likely a monk around, especially at a stupa, who was happy to tell the tale.

“Tree and Serpent” is the result of the imagination, the expertise, and the remarkable labor of John Guy, the Met’s senior curator of South and Southeast Asian Art. He has brought together many stunning pieces, many displayed outside of India for the first time. And he has moved beyond the usual Buddhist sites in the north that we associate with the life of the Buddha to include extraordinary works from South India, where Buddhism thrived for so long. The importance of the show, however, goes beyond its individual pieces.

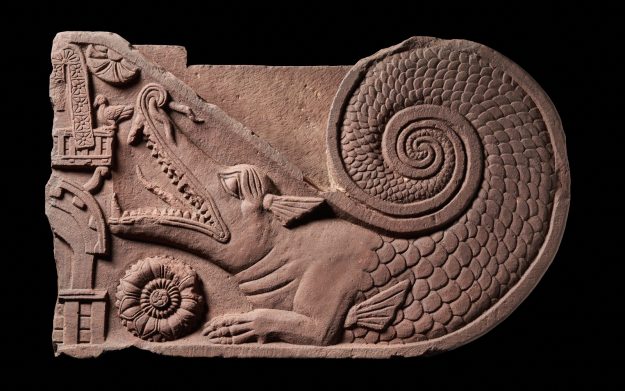

The Buddha obviously lived and died in India; we still go on pilgrimage to the four places that he is said to have recommended on his deathbed: the place of his birth, his enlightenment, his first teaching, and his passage into nirvana. But it sometimes seems that during his eighty years in India, the Buddha’s feet never really touched the ground. Some texts actually say that they didn’t. “Tree and Serpent” corrects our mistake. Ancient India, like so many traditional cultures, had an animated landscape, with all manner of spirits and sprites. Buddhist texts list eight types of nonhumans, none of which are animals. The most common of these were yakshas and nagas, two names that are difficult to translate. A yaksha is often the spirit that inhabits a tree, easily offended and able to both cause harm and bestow benefit. Tibetans had such difficulty translating the term that they rendered it simply as “harm-generosity.” Nagas are serpentine creatures, not quite snakes, often depicted in Buddhist art with the head and torso of a human and the tail of a snake. The Sanskrit term was translated into Chinese as “dragon.” Nagas live beneath the waters in bejeweled palaces. They have magical powers, and their breath is poisonous to humans. Much of ancient Indian religion was concerned with pleasing, or at least not offending, these spirits. “Tree and Serpent” makes clear that Buddhism was deeply grounded in this natural and supernatural land.

The Buddha and his monks lived in a world of spirits who needed to be appeased; many texts are devoted to this. But just as the Buddha commanded the respect of the visible powers—kings and merchants—he also commanded the respect of the invisible: the yakshas and nagas who control the natural world. When the Buddha delivered a sutra, they were often in attendance. Their reverence for him is depicted throughout the exhibition; one of the Buddha’s epithets is devatideva, the “god above the gods.” Thus, “nature worship” is not something that we should consign to the category of the primitive. It has been with Buddhism from the beginning. It is with Buddhism now. The exhibition makes clear that we cannot understand the Buddha until we see what surrounds him. In “Tree and Serpent,” the Buddha comes back home. The beautiful exhibition catalogue, Tree & Serpent. Early Buddhist Art in India by John Guy and published by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, is a major work of scholarship and is not to be missed.

Tree & Serpent. Early Buddhist Art in India, 200 BCE – 400 CE

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, until November 13, 2023

John Guy, Tree & Serpent. Early Buddhist Art in India. New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.