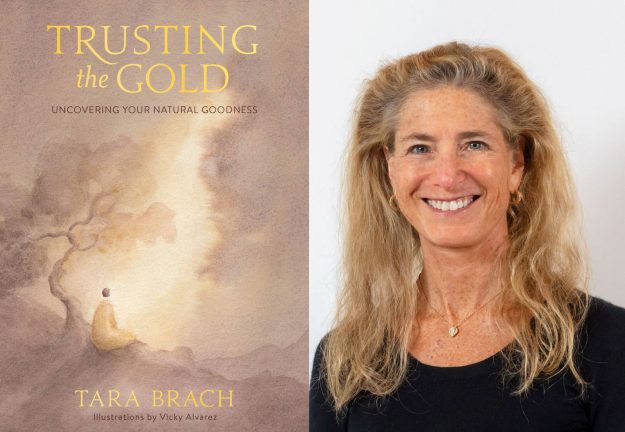

In her latest book, Trusting the Gold, meditation teacher Tara Brach tells the story of a huge Buddha statue from Bangkok that was made of plaster and clay—or so everyone thought. “It wasn’t particularly beautiful, but it was loved by local people for its staying power through the centuries,” Brach explains. But in 1957, a dry climate caused cracks in the statue, and when one monk peered inside, he saw something metallic shining through. Eventually the monks caring for the statue discovered that underneath the clay and plaster laid the largest solid gold statue in all of Southeast Asia.

“Historians and monks believe it was covered over to get through invasions and to protect it from being stolen or destroyed,” Brach says. ”Much in the same way, we cover up our own innate purity to protect ourselves through difficult times.” If we learn to shed these coverings and connect with the inherent goodness in each of us—if we learn to “trust the gold”—we can overcome divisions and treat ourselves and others with compassion.

Given the heightened polarization that defines our current social and political climate, Trusting the Gold is a book for our times. Drawing upon the teachings of the Buddha, it is also timeless. Tricycle caught up with Brach to learn more about the central themes of the book, how she conveys them, and why they’re so important today.

Trusting the Gold focuses on our innate goodness. Why did you choose this subject for a book right now? We’re living in times when there’s a spike in what I call “bad othering.” It’s one of the effects of global trauma, when there’s such a fearful, PTSD society. There’s a hijacking of our survival brain. What happens is that we’re scanning for difference and danger. And that includes the badness, and “others.” A sad example is when groups of people hold different political views and that translates to a deep mistrust and the perception that the other side is morally depraved. And that, of course, fuels violence, and any collaboration—in facing the climate emergency, the pandemic, racism, the growing gap between rich and the poor—becomes impossible.

We’re suffering because we forget our belonging to each other, and we also are cut off from our inner life. When fear is in high gear, we need a way to heal, and one of the ways is to remember goodness—the love and the awareness that lives through ourselves and all beings. In our personal healing, it’s essential to see our goodness and to hold this life with care. That’s the essence of metta [lovingkindness]. As for healing in relationships, I think the greatest gift we give each other is that we become a mirror of goodness. When we see the goodness in others, we call it forward, so it feels like an essential part of healing our world.

It’s true that this “bad othering” feels like one of the defining qualities of society today. For people who aren’t already practicing metta or trying to see the goodness and call it forward, as you say, where can they start? Is there one practice or concept that could help bridge divides if more people followed it? Seeing goodness on purpose—intending to see the human and the heart there—is really powerful. The other piece that is critical is learning to see the vulnerability in others. When we’re angry and blaming, there’s something we’re not seeing: how a person might be suffering. I think of Ruby Sales, a civil rights icon and a deeply wise woman. Her practice is to ask, “Where does it hurt?” She’ll ask that out loud, but she’s also saying, just in her mind, “What’s it like being you?” It helps her to see that under the anger and racial hostility of many poor white people is a feeling of being threatened with becoming meaningless in the society, a kind of growing irrelevance. So that’s her tool: when there’s a sense of difference, to get under that and say, “Where does it hurt?”

If you’re walking in the woods, you see a dog under a tree, and you go to pet it, but it lurches at you with its fangs bared, you shift from feeling friendly to being angry and scared. But then you see that the dog has its leg in a trap, and you shift to, “Oh, you poor thing.” You might not get close to it, because it’s still dangerous, but you’re no longer blaming. It’s no longer a “bad other.” You want to help. So it becomes really important that we learn to see how those we might think are evil in some way are actually suffering.

Can you talk about what the color gold means in the title of the book? Suffering happens when we cover ourselves with our egoic strategies, defenses, aggressions, greed, or insecurities, and when we take ourselves to be the coverings—when we forget the gold. We forget our essence, which is love, awareness, creativity, aliveness, and compassion. “Trusting the gold” means seeing past the covering and remembering that essence so that when we’re together, we see our roles and sense our personalities, but we also sense our basic goodness behind that. Thomas Merton calls that our “secret beauty.”

How can we start to shed these coverings that we come to identify with? There are two related ways that we wake up from being identified with our coverings. One is through meditation practice, where we’re internally attending to what’s coming up, and the other is with other people. In our inner practice, with meditation, I often use the RAIN meditation—recognize, allow, investigate, and nurture—as a way to undo the identification with coverings. For instance, if somebody has been critical and my covering is to be defensive, the art of RAIN is to recognize the defensiveness. The “A” of rain is to allow it. The “I” to investigate and feel that clenching in my body. Then I need to nurture and hold that vulnerability with some compassion. When I do that, the whole defensiveness loosens because there’s this sense of a larger presence, and I’m no longer so identified with the defensive self. That’s just an example.

The second way to undo coverings is with other people. We create safe space with each other and are able to share what’s going on and give each other feedback so we have a clear view of the ways that we’re defending ourselves or grasping. When we do it with others, we realize it’s not so personal, that we all have [coverings]. As soon as you realize it’s not so personal, you’re less identified.

You also write that “if we’re part of a nondominant group in our culture, we take on additional layers of protection to help us face the violence of social injustice and oppression.” Can you talk about that? How can coverings be beneficial? Coverings are most solid when there’s trauma, but even when there’s not trauma, all of us have some basic insecurity that we cover over. One of the places that there’s so much suffering is in racism, where there’s been so much violation, and whenever there’s that kind of violation or violence, the coverings have to be more protective.

What helps people connect is the recognition of their shared coverings, and creating a safe space to hold the coverings with wisdom and compassion. Let’s say the covering is insecurity and a sense of getting judgmental out of that insecurity. If we’re able to acknowledge that, instead of it being my insecurity, it becomes the insecurity. We see that it is just a part of being human. There’s more freedom that way. Another example is Twelve Step groups. People identify patterns of addictive behavior and see how they’ve made themselves small and gotten identified as an addict. But when you’re in a Twelve Step group, it’s no longer “I’m an addict.” It’s a human behavior and there’s more freedom around that.

In the book you talk about the phrase, “real but not true.” Can you explain what it means? It’s a really valuable teaching that I heard first from Tsoknyi Rinpoche, one of my teachers. If you have the thought, let’s say, that you’ll never get the job you want or that other people don’t want to spend time with you, the thoughts are real. They’re happening. They’re electrical events in the brain, and they affect our mood and behavior. But they’re not true. They’re not the reality itself. They’re representations that have been conditioned by our caregivers and culture. This is one of the most profound realizations on the path of awakening: that I don’t have to believe my thoughts. They’re just thoughts. I am not my thoughts. They’re real, but not true. That recognition opens the door to freedom.

The book is a collection of stories from your life, where you often put yourself in the student seat. Why did you choose to structure it this way? My life, like most people’s, has had its share of insecurities and losses, dealing with addiction and challenges in intimacy, the whole thing. So it feels important to name and be real with those places of suffering, and also how those places of suffering can be portals to awakening, compassion, understanding, and trusting goodness and freedom. So I’ve always included personal stories in my writing and teaching. When I do, it creates a relationship. It creates a kind of intimacy and sense that we share our predicament—we’re in it together. It’s important in these times to recognize that—to feel our togetherness. So I decided to draw on my own stories to shine light on that: our shared humaneness, how vulnerability can be a portal, and the potential in each of us to live from an awake heart.

♦

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.