One of my early memories related to books is that of my mother reading me a book about wizardry—young wizards from Long Island, to be precise—before sleep. At one point, she stops and struggles to pronounce an extremely long, multisyllabic name of a cosmic force that temporarily arrives in our dimension to help the main characters. “I don’t know how to read this,” she admits. “Is that phrase in the book?” I ask doubtfully.

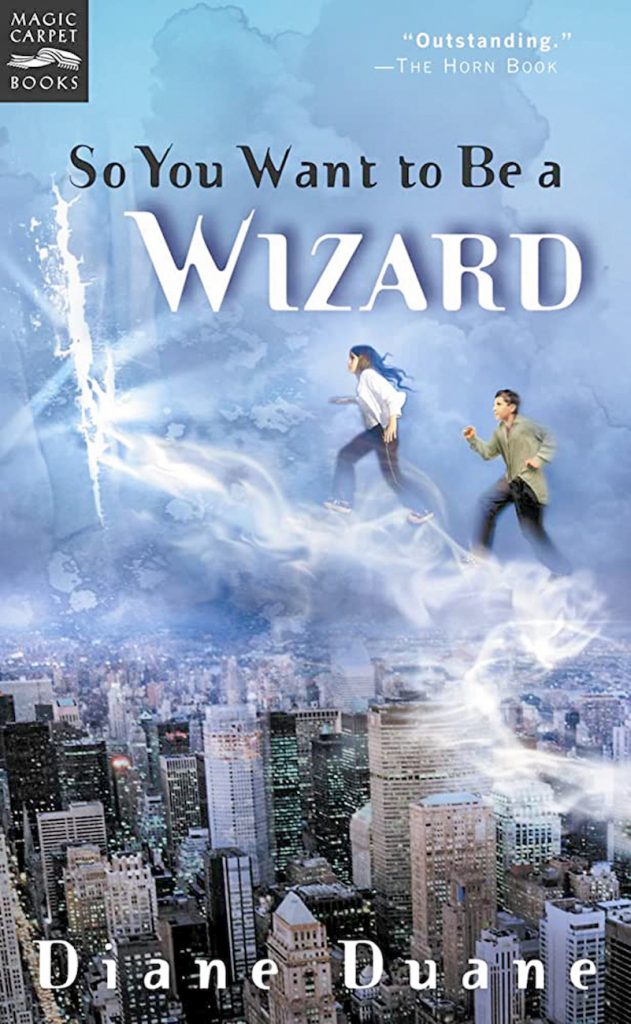

The book charms me so much that I quickly start reading it myself—I’m too impatient to wait for it to be read aloud by someone else in sessions (same reason I’m still not particularly good with audiobooks). Eventually, I reread the book—So You Want to Be a Wizard, by Diane Duane—more than a hundred times before losing my first copy (extremely well-worn by then) during a big family move from the Urals to Moscow.

Although it was years before I could find another copy of the same novel (now always traveling with me as a digital book), I continued reading other parts of the same young adult series. More importantly, the book’s key ideas deeply impacted me, brewing and normalizing the outline of my life and work—things that stemmed from my inner predispositions.

So You Want to Be a Wizard begins with a 13-year-old girl named Nita finding a wizardry manual while trying to escape a beating from a school bully. The manual she picks up is not merely a collection of spells—rather, it’s a self-updating guide that gives one access to the cosmic database of wizardry. The price to pay for that access (and the energy of wizardry itself) is taking an oath to use magic only to protect life and ease the pain of beings: essentially, to slow down entropy and to protect all who live.

Nita does not hesitate to take the oath, and neither did I in those days—reading it out loud numerous times in the hopes of obtaining similar access to special powers beyond the ordinary. While my ability to control natural elements, travel across universes, or manipulate the laws of physics never arrived, the underlying ethic of protecting life stayed deep within me as an aspirational wish until, some years later, at the age of 18, I took the bodhisattva precepts from a visiting Tibetan lama. The wizard’s oath turned into an oath of bodhicitta, now reviewed and contemplated daily: the vow to fully uncover the amazing potential within, to fully wake up for the benefit of all beings, and, on the road toward that, to practice and perfect the six amazing qualities of a bodhisattva: generosity, ethical discipline, and so on, culminating with the wisdom that sees emptiness and interdependence in union. The bodhisattva precepts guide one in applying those qualities to daily life to protect and nurture beings, while the “cosmic bodhisattvas” (like Kuan Yin or Kshitigarbha) provide a steady inflow of inspiration, and, for some people, miracles on the path.

Unsurprisingly, I remember Duane’s formulation of the wizard’s oath almost as well as the words used in the actual bodhisattva precepts. Just like the precepts expressed in slightly different words across the different traditions, the wizardly oath to protect the world can also be shared in different ways. In one of the later books in the series, Duane offers an alternative recension of the same oath, formulated in this alternate way for a young autistic prodigy:

Life

more than just being alive

(and worth the pain)

but hurts:

fix it

grows:

keep it growing

wants to stop:

remind

check / don’t hurt

be sure

One’s watching:

get it right!

later it all works out,

honest

meantime,

make it work

now

(because now

is all you ever get:

now is)

Nita’s journey as a wizard quickly puts her at odds with the one force representing the origin of all problems in the universe–the Lone Power–which represents and embodies the wish to isolate, to exclude oneself from the interdependence and interpenetration of things. Encounters with this force, which sometimes manifests in its menacing avatars and sometimes simply acts through our in-dwelling afflictions, are never fully unsympathetic: even the original troublemaker is shown to be worthy of eventually being reintegrated into the boundless web of life.

Since this process of protecting and rebuilding is all about supporting and strengthening the interconnectedness of life, Nita is inevitably supported by numerous companions, including a fellow teenage wizard Kit (who is himself bullied for being an immigrant), family members, and numerous other wizards from across the universe—human, animal, alien, straight, cisgender, transgender, and multigender from numerous species and numerous corners of the world. That was a powerful lesson for me in finding allies—who might be nothing like you and yet full of love—anywhere and everywhere.

Like everyone striving to master an art, Nita and Kit rely on the support of senior wizards, who, although not showing up as teachers per se (since the wizardly manual provides all the relevant information), still act as guides and advisors. The art of wizardry is embodied in these experienced practitioners; what seems novel and somewhat confusing to a beginner permeates the life of an adept with effortless ease. Showing by personal example is, inescapably, a huge part of Buddhist practice. My trajectory in the dharma would certainly not be as long or joyful if, as an interpreter, I didn’t get a chance to accompany senior practitioners and observe their very way of being, so richly imbued with dharmic qualities and insights.

Interestingly enough—for my young queer mind—the primary advisors of the young wizards turn out to be two men in their 30s, cohabitating in a Long Island house with a few dogs and other wizardly pets (including a talking parrot). Tom and Carl, as they are called, are described as handsome and broad-shouldered, and no particular explanation is given for their shared living situation—except that they work and live together and enjoy the respect of their neighbors and fellow wizards alike.

What’s up with that, the readers later asked? Was this a revolutionary literary step for a children’s book originally published in 1986? In retrospect, I believe so. When asked about the romantic implications of Tom and Carl’s situation, Duane politely declined to elaborate, explaining that the two are based on two specific friends and citing the need to respect their privacy (and their actual familial arrangement, which might be completely different). Over time, she instead introduced a wide range of openly queer characters that joined the series’ cast or were always present in her novels aimed at adult audiences. However, for me personally, a basic level of representation was already right there from the very first book: two men can cohabitate, do wizardry together, help others, and adopt pets. As someone who’s relatively private about his personal life, I find that level of detail quite sufficient—and extremely relatable.

Quite importantly, in Duane’s universe, Tom and Carl’s situation is simply not an issue of anyone’s concern. She creates an alternate reality, similar to the one in the sitcom Schitt’s Creek in which homophobia is not given a place. This equally pertains to the issue of being trans: gender-affirming magical transformations are described as absolutely permissible in the eyes of the Powers that preside over magic, because why not? An author of YA books who honors trans people in her work? I bow to that.

I keep revisiting Duane’s novels to this day. My other favorite in the series, A Wizard Abroad, unpacks Irish mythology and introduces the concept of a land haunted by old energetic traumas (something not unheard of in the chöd lineage of Buddhist practice), all against the backdrop of Nita developing her first crush. This book and a few others remain part of my lunch table collection, and I still find their moral lessons personally pertinent.

I’m forever grateful for how much one book can do in offering both representation and ethical guidance.

What’s more, I’m forever grateful for how much one book can do in offering both representation and ethical guidance. The wizard’s oath and its ethos did not make me a Buddhist, and Tom and Carl certainly did not make me queer. They just helped me normalize what I already knew about myself and ethics, offering a ray of hope and a glimpse into something bigger. One thoughtfully written book about kindness and interdependence was enough for that (though we need hundreds and thousands more). In much the same way, when fellow queer people ask me whether there’s anything in Buddhism to support the validity of our existence, I usually just need to quote one powerful ally—such as Garchen Rinpoche, with his simple and powerful words on queerness—to give them hope. Yes, the more representation and support, the better. But even one person performing the truest wizardry of kindness, the wizardry of living and letting live, is sometimes enough to keep us going.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.