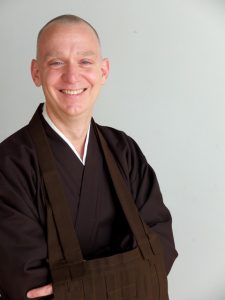

Brooklyn Zen Center’s Undoing Patriarchy and Unveiling the Sacred Masculine group is a response to the unacknowledged forms of patriarchy that exist within Buddhist communities as well as society at large. Co-facilitated by Greg Snyder, co-founder and president of BZC and senior director of Buddhist Studies at Union Theological Seminary, and Lama Rod Owens, guiding teacher for Radical Dharma Boston Collective, the group meets monthly and had its second annual weekend retreat in January.

Here, Snyder speaks about how Buddhists can use their practice to confront patriarchy rather than conform to it.

Why did you start this group?

Our first retreat, which Lama Rod Owens and I co-led in January 2017, was an attempt to address the fact that patriarchy is still thriving in the Buddhist tradition despite the tools for self-examination that Buddhism presents us with. During that retreat, we tried to examine internalized patriarchal masculinity the same way we’d examine greed, hate, and delusion. The participants came out with a desire to meet regularly, so we started the monthly group.

The purpose is similar to that of BZC’s monthly Undoing Whiteness and Oppression group. Undoing Patriarchy is just a group of men who are trying to take responsibility for how they represent their gender identity.

Has the group changed over time?

It became evident right away that we should understand masculinity as an energy rather than something tied to a particular body. From there we’ve been trying to find a nonviolent, loving expression of that energy.

As the group continued, it became more obvious that supporting one another is extremely important. These are cisgender and transgender men with many different racial identities, but there is a feeling of love in the room despite all the violence expressed historically between the various groups. This loving connection is one of the most critical pieces of undoing the typical male relationship, which usually involves hierarchy, competition, and apathy toward each other.

Take me into the room. How is it supposed to work?

It’s important to say that I don’t know how it’s supposed to work. We have to give up on knowing, because we can’t know. No one has ever undone patriarchy.

It’s also important to realize that masculinity is not synonymous with patriarchy. So during the retreats, the first day starts with defining patriarchal masculinity, which is the historical form where all things masculine are considered superior to to all things feminine. The dichotomy is held strictly, reinforced socially and employed as a means of domination over women’s bodies and lives. This domination of the feminine is internalized by men in such a way that all attributes associated with the feminine are violently repressed, the most obvious being a whole range of experiences and emotions necessary for intimate relationships. The repression expresses itself as misogyny.

The next step is to explore how patriarchal masculinity has harmed us. If we don’t see how patriarchy harms us, we don’t start releasing ourselves from it.

We explore this harm by asking ourselves a lot of questions: How do we express need? How do we meet our own needs? How do we meet the needs of other men? How do we have intimate experiences with other men?

Sometimes we do an activity where men sit facing each other with their knees touching. They can choose if they want to hold hands or not. Then they express to one another how masculinity failed to meet their needs. During this activity, the body is moving past the ways men, especially heterosexual men, often feel they are allowed to interact. They’re touching and facing each other while expressing their feelings rather than talking into space.

Patriarchy’s message is that men should provide but shouldn’t need support. This creates extremely fragile men who won’t communicate their needs. As a result, women have to do the hard and often unrecognized labor of dealing with men’s fragility. If men came out of the workshop understanding just this, I’d be happy. Once you realize this, you can’t look at your relationships with women the same way.

Is anti-patriarchy work doable as an individual, or is community necessary?

I think community is a necessity for anything that’s “against the stream.” Systems like patriarchy and white supremacy are power relationships. When somebody gives power up, they’re often met by social exile, which can be quiet but is very painful. For instance, if you don’t express yourself in a patriarchal way at work, you might be passed over for a promotion because other men don’t trust you. So we need a community that encourages and strengthens us.

The community also acts as a mirror. Without a mirror, you don’t know when you’re manifesting patriarchy. It’s like a Twelve Step group. We’re addicted to particular identities, and we need a group of other addicts to say, “You’re not seeing how you’re behaving.”

In dharma talks you’ve given, you have mentioned that this kind of work isn’t about self-condemnation, but upright resolve. What’s the difference?

Many men try to carry everything on their back, and when they fail they feel self-hatred. In this sense, self-condemnation is just the flipside of patriarchal heroism. It’s a way of not taking responsibility. It’s easier to hate ourselves than to take responsibility for our interactions.

We need upright resolve, because patriarchy manifests itself in all our interactions. We have to recommit ourselves to taking responsibility moment after moment. No moment of realization allows you to say you are done. If that were the case, you could just claim expertise and become the patriarchal expert on undoing patriarchy.

You mentioned that there’s a need to address patriarchy within Buddhist communities specifically.

[Laughs.] The tradition is incredibly patriarchal. Women have been put second for 2,500 years. To this day we are following the so-called law that requires a certain number of women and men be present to ordain women, which prevents the full ordination of Theravada and Tibetan nuns.

Further, many of the tradition’s stories about women were created by men for a male audience and frame women’s bodies as objects of male practice. Negative images of women’s bodies were often used as objects of meditation in order to cultivate detachment from sexual appetite in male monastics. While these practices should be understood within their context and not generalized as an overall Buddhist attitude toward women, they still risk framing women’s bodies as the source of the problem, rather than making men take responsibility for their appetites.

The good news is that in American Buddhism, we have started absorbing the lessons of feminist movements. This has made a difference. For example, in the American Zen tradition women are transmitted in the same lineage as men.

Still, many of the characteristics of Zen are patriarchal. For example, in dokusan [a private interview between a Zen teacher and student], it’s traditional for a student to prostrate up to three times to their teacher. In a monastery where 20-year-old boys bow to 60-year-old men of the same culture and ethnicity, this may make sense. However, when you bring the same practice to urban dharma centers where a black woman might be prostrating to a white man, it’s impossible to ignore our nation’s history of social and interpersonal violence. Such patriarchal forms should be dropped when they might cause violence or entrench relationships of domination. We should drop them carefully, however, as these traditions do hold centuries of wisdom.

Where should Buddhist communities that want to begin doing anti-patriarchy work start?

Start by learning what patriarchal masculinity is. Read bell hooks and Audre Lorde. bell hooks is particularly great because she identifies as Buddhist.

Then bring together the people in your community who want to have a conversation. To start it off you can invite somebody like Lama Rod Owens to do a workshop. After that just keep meeting.

You’re not going to get it right. The shame men are trained to feel when they don’t have the right answer is one of the first things we have to give up. If you have no idea what you’re doing, good. Start.

Meditation teacher Sebene Selassie and your wife, Laura Laughlin, who is a dharma teacher at BZC, are facilitating a two-weekend undoing patriarchy retreat for women this February. Why keep the men’s retreat and women’s retreat separate?

Safety. Having men talk about these things in front of women could be re-traumatizing for the women. Also, men may feel safe saying things they don’t feel safe saying in front of women. It’s important to remember that some men had patriarchy quite literally beaten into them until their emotions and vulnerability were gone.

Once the groups have matured enough, it might be very helpful to bring them together. It’s really important for men to hear about women’s experiences. It’s also helpful for women to hear men speak from vulnerable places.

Any final thoughts?

I believe that for Buddhism to be relevant in this society it has to turn toward social identity.

When Buddhism went to China it had to adapt to ideas that the Chinese would not give up. For example, the Chinese believed everyone has access to the fruits of a spiritual path. So tathagatagarbha, one’s inherent potential for enlightenment, became central to all schools of Chinese Buddhist thought.

Similarly, Buddhism in the United States cannot ignore the Abrahamic notion of justice. It will not be taken seriously if it does. A sense of justice is rooted too deeply in us. Even when we ignore it, we know we’re ignoring it. As Buddhists we will have to reinterpret justice to make it consistent with a nondual and compassionate understanding of the world. I don’t see any other way for Buddhism to flower into its full potential.

Finally, the benefit of doing this work is not just decreasing the harm we cause ourselves and others, but the emergence of a truly whole being. We get to be who we are instead being our history of social violence. That is worth everything.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.