The first piece of wisdom I gathered as a 21-year-old going to India in 1971 was: Don’t do it in mid-June. That’s when the pre-monsoon season hits its hot, dry peak. Oddly, there were bizarre ways—mostly the visual and sensory overload—in which India resembled Las Vegas, but universal air-conditioning was not one of them. Into this stifling heat arrived thousands of baby boomers who had come overland. Ground transportation cost roughly $40 from Istanbul. Buses, trains, and shuttles would take you in relative comfort—really, the transportation itself wasn’t that bad—through Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and into India. The French called the route Le Grand Boulevard. At that time, the dollar got about 11 rupees on the black market (7 in banks, though I never met a foreigner who had ever entered one), and a frugal person could live fairly well on $1 or so per day. I don’t remember paying more than 60 cents for a place to stay. An Indian thali meal cost around a rupee or two. A cup of chai was pennies. On the downside, there was no such thing as bottled water, and stomach problems were endemic—and you don’t want to hear about Indian bathrooms.

If the first problems were the heat and the gastrointestinal distress, the next was figuring India out. A few years later, Lonely Planet published an almost overachieving guidebook that decoded travel in the subcontinent. But in 1971, a lot was left to luck. Mostly you learned by bumping into people who knew their way around.

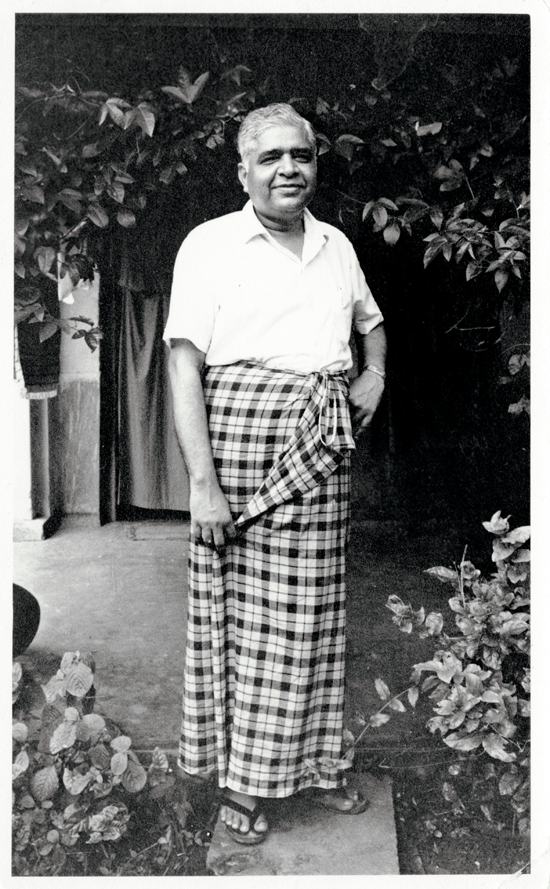

My luck improved when I stayed at a “rest house” near New Delhi’s Connaught Place, where an Anglo-Indian woman rented space in her crowded second-floor apartment to foreigners. She also had a thing about letting stray dogs wander around. Whatever your mind conjures up about the wretched condition of Indian stray dogs is right. It was the kind of place where you would lie on a decrepit Raj-era couch in a muggy room thinking, “This is not the reason I came 8,000 miles to India,” while a mangy dog licked your hand. What got me out of there was a guy named Alan Abrams, who would later go on to a successful career as a film sound editor. He told me he’d heard of a Buddhist meditation teacher named Golunka-ji, and if we left on the 15-hour train trip that night, we could travel the 650 miles to Bodh Gaya in time for a 10-day course. What was there to lose? The trip itself was the standard overcrowded third-class Indian train ride. I think we had tickets, but it didn’t seem to matter. We found the ashram where the meditation course would be held easily enough and learned the teacher was not “Golunka-ji” but S. N. Goenka, who was then 47. An ethnically Indian student of Burma’s Sayagyi U Ba Khin, Goenka had begun teaching Vipassana in India two years earlier. Attending courses at the centers he later started would be by donation only, but back then we had to contribute to the expenses, around $5 each. There were about 50 students, almost equally split between male and female, Indian and foreign. What we had in common is that most of us were truly terrible meditation students.

The retreat was supposed to be held in silence, but people spoke incessantly, the Indians probably even more than the foreigners. What you discovered right away is that if you weren’t keeping silent, a meditation course was a great place to meet people. The Indians were curious about the hippies who had descended on their country, and before this trip I hadn’t met anyone from India. So we would hang out in the garden and talk. There were some nice times.

For his part, Goenka really only insisted on us coming to the three-times-daily group meditations. In fact, we were supposed to be meditating most of the day—“maintaining the continuity of practice,” in his words—beginning at four a.m. and ending at nine p.m., but that wasn’t enforced. For most of us, those three sessions were hard enough. The foreigners had no experience sitting cross-legged on a hard floor, and we were crammed knee-to-knee in a room with little ventilation. (Sweating profusely was just one of the sensations we were told to watch with equanimity.)

I think the biggest revelation, at least for the foreigners, was how completely out of control our minds were. Meditation held a mirror up to our laissez-faire mental chaos. No one had told us, in my case certainly not in Catholic school, that there was something wrong with a mental state where internal dialogue yammered away 24/7. Goenka would use the analogy of sprinkling water on a hot metal plate to describe the way Vipassana would slowly quiet our minds. It was going to take something like a Niagara Falls of meditation to quiet this mind.

Over the next year, I took more courses with Goenka-ji in India. A notable one was in December 1971 in an old residential section of Bombay. A few days after the course began, so did the Indo-Pakistani War. One night the sky lit up with hundreds of anti-aircraft bursts when the Indians thought a Pakistani jet was approaching the city. (I never heard a confirmed reason for the shooting, although rumor had it that the military had mistakenly targeted an Air France flight.) You could hear the shrapnel from the shells landing like hard rain on the metal roofs.

None of this seemed to bother Goenka. On top of his less-than-perfect students and a location in a Bombay neighborhood whose population density made New York’s East Village seem like Wyoming, now he had anti-aircraft shells exploding over his meditation course. But he just kept at it. Maybe that was as much a part of his teaching as the Vipassana. His gentle persistence and an amicable tolerance for his students’ limitations led to his having 120 permanent meditation centers around the world. And while I was certainly not one of his better students, I keep at the Vipassana myself. When I heard of his death on September 29 at 89, I realized that he had been a spiritual father figure to me. Those meditation courses had changed my life. As chaotic as the whole process of traveling to India had been, there was a reason to make the trip: those kinds of teachings, that kind of wisdom, and a meditation practice that would integrate into your life simply weren’t available then except in India and Southeast Asia. I’d like to think that the hundreds who studied with S. N. Goenka in those early days repaid him, in part, by becoming the ants who carried the dharma to the West.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.