Tell me, are you Western yogis really interested in nibbana?

The Burmese interpreter’s piercing brown eyes looked into mine as he waited for an answer. U Mya Thaung was a dignified, precise man of seventy-three, with a mischievous smile. He would interpret for the retreat I would be attending. In the sweltering waiting room of the Rangoon airport, Burmese men wearing sarongs looked at me curiously. I, too, was wearing a traditional longyi, but my Voit high-top sneakers stuck out conspicuously beneath the blue-checked material. We waited for the dilapidated 1950s prop plane to refuel for our flight to Mandalay. In response to U Thaung’s question, I mumbled something like “Some of us are and some are not”—but it continued to haunt me throughout my three-week retreat at the fourteenth-century monastery called Kyaswa.

I was one of thirty-three yogis (meditator/practitioners) who would meditate in the vipassana tradition at Kyaswa, ten kilometers downriver from Mandalay, at the third annual Foreign Yogis’ Retreat. Vipassana had been practiced continuously at Kyaswa for the past six centuries, but it had only recently opened to Westerners for three weeks each year. It was here, in the hills of Sagaing, that the Burmese Satipatthana method of insight meditation had its origins. At Kyaswa, perched high atop the limestone cliffs overlooking the Irrawaddy River, I would hear the dhamma spoken by Sayadaw U Lakkhana—a renowned meditation master and disciple of Mahasi Sayadaw, and by Michelle McDonald-Smith, an accomplished vipassana teacher associated with the Insight Meditation Society in Barre, Massachusetts.

Our plane chugged noisily through the clouds of upper Burma, when someone called out—“There’s Mandalay.” I looked through the airplane window and saw hundreds of bleached-white pagodas with chedis (steeples) pointing up at us like benign missiles.

At last I was in a culture that was brimming with Buddhism: Seven thousand monks and nuns live in the Sagaing region; Burmese calendars number the year 2543, the years since the Buddha’s birth; and on New Year’s Day, instead of fireworks and liquor, caged birds are set free. Even much of written Burmese comes from Pali, the language of Theravada Buddhism. This was why I had temporarily left my wife and Santa Fe law practice and traveled halfway around the world to practice meditation in a land where the teachings of the Buddha were vibrantly alive—but was I, indeed, truly interested in nibbana?

We rode through the outskirts of Mandalay in the monastery’s open truck, just as the dinner fires were being kindled along the roadside. Billows of wood smoke mixed with vehicle exhaust filled the evening air as we careened between goats, dogs, pigs, children, chickens, and monkeys, potholes and produce carts. We arrived at the monastery after dark, and the interpreter took me directly to meet the Sayadaw. U Lakkhana, with his kindly, round face and spectacles slightly askew, was the spitting image of my “Uncle” Abe from the Bronx—my Dad’s World War II army buddy. He welcomed us and I greeted him in my rudimentary Burmese—“Min-gala-ba” (“It’s a blessing”). The Sayadaw chuckled, then commented on my longyi, “So you’re Burmese already!” He even spoke like Uncle Abe and I felt at home—that is, until I saw my living accommodations. When I entered my room, I was greeted by the din of hundreds of baby mosquitoes. My room was in the “barracks,” the designated breeding ground for the mosquitoes of the Irrawaddy Valley. One of my windows faced a limestone wall one foot away, and the other window opened onto an open drain. My coconut-husk mattress had the resiliency of a New York sidewalk—my mind recoiled. Then, I remembered the response Jack Kornfield gave to an overzealous yogi when he asked about practice in Burma and Thailand: “The practice of Asia is Asia.” That evening I counted my blessings as I prepared for bed, taking refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and my mosquito netting.

Tabodwei, first day of the waning moon—February 1

I awoke at three a.m. with the morning bell accompanied by a howling pack of wild dogs. I rolled out from under my mosquito netting and made a cup of tea. Another bell rang, and I was off to the meditation hall for the four a.m. sit. I approached the hall in the darkness and illuminated, golden chedis suddenly appeared, shining from across the Irrawaddy. I was mesmerized by the ethereal spires floating in the night sky as barge horns sounded in the distance. This was Burma!

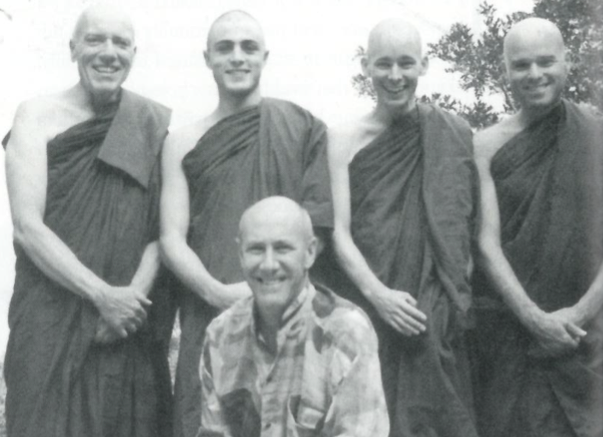

After our first sitting I began my walking meditation in the limestone courtyard, with the yellow light of dawn. Then a grinning monk approached me. He had sat next to me nine years ago at a retreat in New Mexico. He knew me by the Grateful Dead decal still affixed to my meditation bench. Now he wore the beautiful, ochre robes of Burma, having ordained several months ago. His Buddhist name was U Vappa, which means “sown seeds” or “teardrop.” He and four other Western monks and a nun traveled from Rangoon to sit at this retreat. I asked U Vappa what it was like practicing in Asia. He laughed, then quoted his teacher, Sayadaw U Pandita, who’d said that Western yogis were much better at observing Noble Silence than Burmese monks except in one place—their minds.

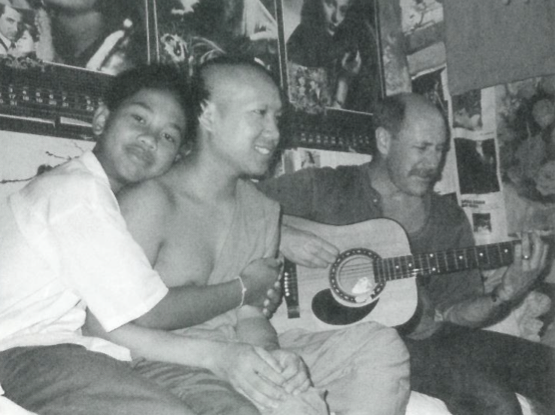

I suspected he was right. The other Kyaswa yogis in attendance represented the spectrum of Western lay practitioners: a scientist from Israel, a journalist from Florida, and a crew of “Dharma bums” living between the States and Burmese monasteries.

The bell rang at 5:30 and we assembled for our breakfast procession, which observed a specified order—monks, nuns, laymen, then laywomen; this made me uneasy. It soon became apparent that the women were the most diligent practitioners at the retreat. I wanted to show respect for our Burmese hosts, but not at the expense of the respect I felt for the women. I recalled the words of Zen Master Dogen—“Wanting to hear the Dharma, and wanting to get liberation, never depend on whether we are a man or woman.” Halfway through the retreat I quietly took my place at the back of the daily processional.

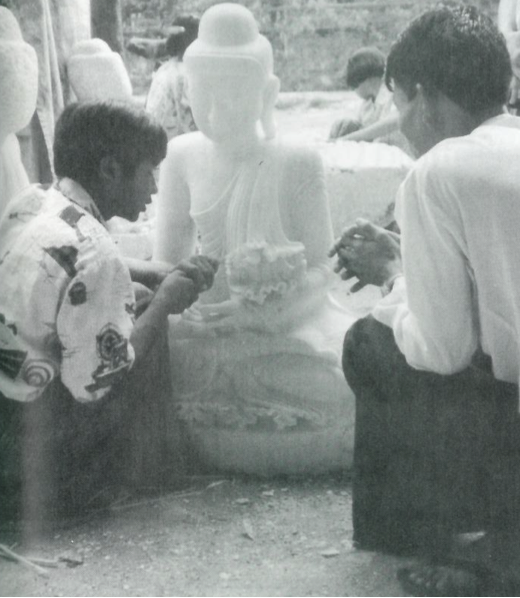

Sayadaw U Lakkhana was very progressive in most respects. Not only was he teaching alongside a Western teacher, but a female Western teacher, and he permitted men and women to sit together in the hall. I didn’t realize how radical this was until I visited the pagodas of Mandalay and Rangoon, where wooden barriers keep women at a safe distance from the Buddha statues. I was delighted when U Lakkhana repeated the words of the Buddha, spoken in the Kalama Sutta—“Don’t believe something just because I say it, only through practice will you discover the truth.”

Breakfast included rice porridge, fried bread cakes, pinto beans, Nescafe, and amazingly sweet tangerines. The Buddha wisely chose tangerines to teach eating meditation to children. Our food was donated by villagers of Sagaing and Mandalay and, at first, it was difficult accepting dana from the residents of a country where malnutrition is rampant and a good wage is 30 cents per day. However, most Burmese enjoy supporting monastic practice, even that of foreigners. We were allowed to pay for some of our meals, but not to the extent where we would interfere with the villagers’ practice of dana. We chanted blessings to our benefactors for their generosity before every meal, then they happily watched us eat. I further acknowledged these gifts by renewing my dedication to our practice—and it was, unquestionably, “our” practice.

Steven Smith, the founder of our retreat, and U Lakkhana had several public works programs underway. They were building a tuberculosis wing at a local hospital and relocating the one-room schoolhouse that flooded whenever the Irrawaddy rose. That evening, Steven’s wife, Michelle, gave a dhamma talk in which she asked us whether we could listen to the song of a bird and the suffering in this world with the same care and compassion.

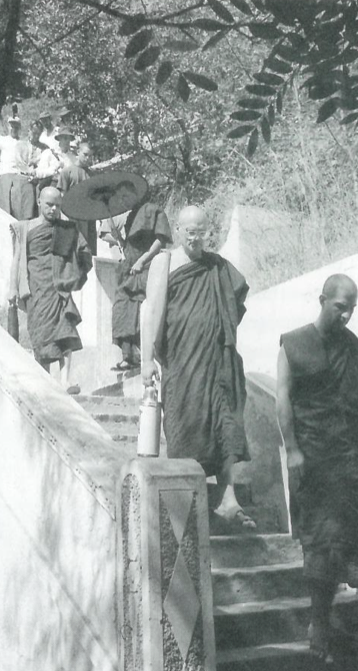

While discussing the meditative hindrance of slothfulness, the Sayadaw quoted a Burmese saying: “One hundred steps after each meal.” Inspired, I found a place for after-breakfast aerobics—the 440 stone steps leading up the cliff behind the monastery. I ran up the steps only to find another monastery perched high upon the hill. We would soon hear the monks at this monastery chanting the Patthana from the Abhidhamma continuously for seven days and nights, but for now I heard only the tiny chedi bells, tinkling in the breeze, sending their prayers in all directions. My only company on these forays was the occasional delinquent, novice monk sneaking a cheroot along the old stairway. Every morning, from atop the stairs, I watched the blood-red sun peak over the Irrawaddy as life on the river began. Fishermen crossed the delta, launching their rickety wooden boats through the reeds; morning barges appeared around the bend drifting downriver from Mandalay, bound for the bronze and lacquerware markets of Pagan; women carried baskets of corn harvested from riverbed gardens, while ox carts inched along rutted roads. Children carried water on their heads in burnt-sienna clay pots, just as they had done since ancient days. Village life flowed in rhythm with the Irawaddy in this valley where life seemed to honor life.

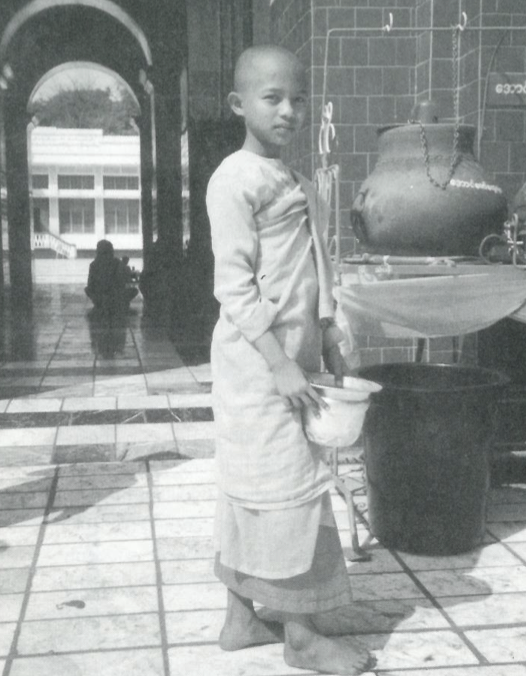

The Burmese call midday the time “when feet are silent”—“And not for nothing,” as Uncle Abe would say. The temperature broke 100 degrees in the shade. Nothing moved. Monastery dogs didn’t bother shaking off the flies. The meditation hall felt like a sauna and even the Irrawaddy looked parched. This was the time when we engaged in that sublime experience known as the “Kyaswa shower.” Most places in rural Burma are without hot water and our monastery was no exception. Nevertheless, we devised a solution. We were issued plastic laundry buckets, which we filled with water, then placed in the morning sun—by noon we had piping hot water for bathing.

We finished our lunch by noon to honor the Buddha’s sixth precept—not to eat after midday. Besides the customary lay precepts, the Sayadaw had us take a ninth precept—to stay with a tranquil mind infused withmetta (lovingkindness) toward all living creatures. As night fell, and the mourning doves sang, we ended the day by chanting in Pali, honoring all beings in all realms, wishing them well.

In U Lakkhana, I had expected the fierce manner for which Burmese Sayadaws are renowned, yet our Sayadaw was a man of strength and kindness and one (continued from p. 71) of the most beloved meditation masters of Burma. The Burmese have a saying: “Ten thousand birds can perch in one good tree.” Villagers came to take his photograph during his talks, yet he never seemed to notice. One day I held the door for the Sayadaw as he approached the meditation hall. There were several cameras poised and ready, as well as the entire complement of yogis awaiting his entrance. The Sayadaw came to the doorway and carefully wiped his feet. I had never seen anyone attend to a simple task with as much presence. At that moment there were no yogis waiting, no dhamma talk to give—just feet to be wiped. I learned more about mindfulness in that moment than at any other time during the retreat.

Tabodwei, 14th day of waning moon—Valentine’s Day

I devoted the day to metta practice, thinking of Sally, my wife of 17 years, who has always supported my practice wherever it has taken me. The metta flows smoothly as I realize that the most valuable “practice” of my life is our relationship.

Then came my interview with the Sayadaw. I entered his kuti (hut) and immediately began to crow about my rapturous forays into the states of absorption, when the Sayadaw cut me off. He said that only one thing mattered, and that was my understanding of suffering and its causes. Then, it was as if he looked through my eyes, sensing the pain I held within. An aura of sheer compassion emanated from him. He rang the bell signaling the end of our meeting—I bowed three times and left. I went back to the hall and tried to meditate, but I felt like I’d swallowed a coconut. I recalled the interpreter’s question: Was I here for liberation or for some sort of dhamma-chic to be gained by meditating in Burma? I returned to the image of U Lakkhana’s kind face. It was a face that reflected the immense suffering of the Burmese, their devastating poverty, the centuries of warfare they have endured. But, his face also reflected their constancy, their patience, their faith, and their heart. They seemed to understand the Buddha’s words from the Dhammapada, “Hatred never ceases by hatred but by love alone.” Then I recalled the anguish I’d seen in the eyes of my Uncle Abe, whose son, my friend, leapt to his death from the roof of a New York apartment building several weeks earlier. The dam burst and I cried and cried.

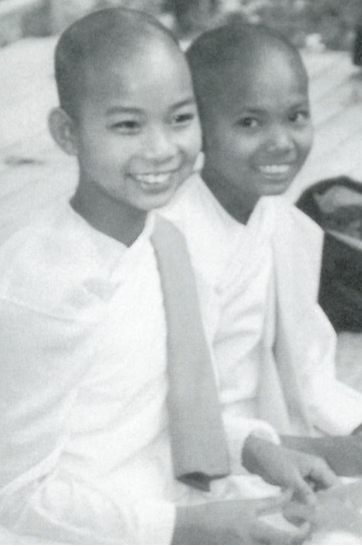

I continued to sob as I walked along the limestone paths on into the night. Through my sadness I felt at home on those paths—the paths walked upon by countless others in pursuit of truth and understanding in this mad world. Yet it seemed that finding “the truth” was not the point. Attaining the goal was in some way less important than the sincerity of one’s quest. As the tangerine-colored moon rose over the Irrawaddy, the dulcet voices of the young monks and nuns chanting the suttas rose in a dissonant harmony. It was the same harmony sung by children for more than two millennia—passing on the teachings of the Buddha from voice to voice, heart to heart, in an unbroken chain echoing across the Irrawaddy Valley—and into the recesses of my heart. The children’s songs mingled with the perfumed frangipani in the warm night air.

Tabaung, fifth day of the waxing moon—February 20

The Sayadaw surprised us by ending the retreat a day early and sending us on a dhammic field trip. With senses freshly cleansed and blasted wide open, we boarded a hired bus to visit the pagodas of Sagaing and Mingun. I sat next to the interpreter for the ride. As we bounced along the dusty roads he spoke of his boyhood, of wild leopards that roamed the hills, and crimson-blossomed lappen trees that frightened him at night with their eerie, gnarled branches. He pointed out the weathered, wooden monastery where he had lived as a young, novice monk. Our bus continued past castor plants and kapok trees, past children knocking ripe tamarinds from branches with bamboo poles. Then I asked U Thaung the same question he had asked me three weeks ago. He had translated all of our interviews with the Sayadaw—what did he think, were we really interested in nibbana? His mischievous smile reappeared, this time with palpable warmth, and he repeated my previous response—“Some are, some are not.” That was his generous way of leaving the door open to us. U Thaung would never say anything that would get between us and our liberation.

When the bus returned to the monastery, we said our good-byes and shook hands, then U Thaung said—“Let’s do it American style,” and gave me a big hug.

As I crammed myself into a coach-class seat headed for Los Angeles, the interpreter’s initial question resurfaced. In the midst of the confusion and chaos of the overfilled flight, it became apparent to me that all beings are interested in liberation, notwithstanding the artless manner in which some of us—certainly myself—tend to pursue it.

of the most beloved meditation masters of Burma. The Burmese have a saying: “Ten thousand birds can perch in one good tree.” Villagers came to take his photograph during his talks, yet he never seemed to notice. One day I held the door for the Sayadaw as he approached the meditation hall. There were several cameras poised and ready, as well as the entire complement of yogis awaiting his entrance. The Sayadaw came to the doorway and carefully wiped his feet. I had never seen anyone attend to a simple task with as much presence.

At that moment there were no yogis waiting, no dhamma talk to give—just feet to be wiped. I learned more about mindfulness in that moment than at any other time during the retreat.

Tabodwei, 14th day of waning moon—Valentine’s Day

I devoted the day to metta practice, thinking of Sally, my wife of 17 years, who has always supported my practice wherever it has taken me. The metta flows smoothly as I realize that the most valuable “practice” of my life is our relationship.

Then came my interview with the Sayadaw. I entered his kuti (hut) and immediately began to crow about my rapturous forays intothe states of absorption, when the Sayadaw cut me off. He said that only one thing mattered, and that was my understanding of suffering and its causes. Then, it was as if he looked through my eyes, sensing the pain I held within. An aura of sheer compassion emanated from him. He rang the bell signaling the end of our meeting—I bowed three times and left. I went back to the hall and tried to meditate, but I felt like I’d swallowed a coconut. I recalled the interpreter’s question: Was I here for liberation or for some sort of dhamma-chic to be gained by meditating in Burma? I returned to the image of U Lakkhana’s kind face. It was a face that reflected the immense suffering of the Burmese, their devastating poverty, the centuries of warfare they have endured. But, his face also reflected their constancy, their patience, their faith, and their heart. They seemed to understand the Buddha’s words from the Dhammapada, “Hatred never ceases by hatred but by love alone.” Then I recalled the anguish I’d seen in the eyes of my Uncle Abe, whose son, my friend, leapt to his death from the roof of a New York apartment building several weeks earlier. The dam burst and I cried and cried.

I continued to sob as I walked along the limestone paths on into the night. Through my sadness I felt at home on those paths—the paths walked upon by countless others in pursuit of truth and understanding in this mad world. Yet it seemed that finding “the truth” was not the point. Attaining the goal was in some way less important than the sincerity of one’s quest. As the tangerine-colored moon rose over the Irrawaddy, the dulcet voices of the young monks and nuns chanting the suttas rose in a dissonant harmony. It was the same harmony sung by children for more than two millennia—passing on the teachings of the Buddha from voice to voice, heart to heart, in an unbroken chain echoing across the Irrawaddy Valley—and into the recesses of my heart. The children’s songs mingled with the perfumed frangipani in the warm night air.

Tabaung, fifth day of the waxing moon—February 20

The Sayadaw surprised us by ending the retreat a day early and sending us on a dhammic field trip. With senses freshly cleansed and blasted wide open, we boarded a hired bus to visit the pagodas of Sagaing and Mingun. I sat next to the interpreter for the ride. As we bounced along the dusty roads he spoke of his boyhood, of wild leopards that roamed the hills, and crimson-blossomed lappen trees that frightened him at night with their eerie, gnarled branches. He pointed out the weathered, wooden monastery where he had lived as a young, novice monk. Our bus continued past castor plants and kapok trees, past children knocking ripe tamarinds from branches with bamboo poles. Then I asked U Thaung the same question he had asked me three weeks ago. He had translated all of our interviews with the Sayadaw—what did he think, were we really interested in nibbana? His mischievous smile reappeared, this time with palpable warmth, and he repeated my previous response—“Some are, some are not.” That was his generous way of leaving the door open to us. U Thaung would never say anything that would get between us and our liberation.

When the bus returned to the monastery, we said our good-byes and shook hands, then U Thaung said—“Let’s do it American style,” and gave me a big hug.

As I crammed myself into a coach-class seat headed for Los Angeles, the interpreter’s initial question resurfaced. In the midst of the confusion and chaos of the overfilled flight, it became apparent to me that allbeings are interested in liberation, notwithstanding the artless manner in which some of us—certainly myself—tend to pursue it.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.