At the meditation center where I used to practice, my teacher told a story about a time when he had lived in Korea and studied with a Zen monk. One of the nuns in the community had died, and at her funeral the monk wept uncontrollably and hysterically, in a way that was almost embarrassing. My teacher, relatively new to the practice, was surprised that the man hadn’t shown more equanimity, and brought the matter up at an interview. The monk burst into laughter. That nun had been a dear friend of his, he said. They had joined the community at the same time, and he was sad she was gone. He had expressed his grief when he felt it, and now could go on. Liberation wasn’t a matter of acting some particular way, but feeling how you felt, whatever the situation.

My teacher ended with a punchline. “I think I’d been reading too much Alan Watts.” The class roared with laughter.

That remark seemed to express a common view of Alan Watts, that he hadn’t been quite authentic, hadn’t known Zen from the inside. He had learned his Buddhism from books, and his view of liberation was facile, didn’t acknowledge the real work that was a part of it. He had been a sixties character, an alcoholic and a womanizer, one of the early experimenters with psychedelics. He had gotten people started on the path, but they soon moved beyond him.

Ah yes, that laughter seemed to say. I remember when I was young and foolish.

By some coincidence, I had happened across the following quotation that week in The Way of Zen.

The story is told of a Zen monk who wept upon hearing of the death of a close relative. When one of his fellow students objected that it was most unseemly to show such personal attachment he replied, “Don’t be stupid! I’m weeping because I want to weep.”

Watts knew more than his old fans remember.

I hadn’t read Alan Watts when I was young. I had come late to the practice—late to any interest in Buddhism at all—and Watts was an important writer of my maturity, not a forgotten figure from my wayward youth. I believe that he was not only a popularizer of Eastern religions, but a fascinating thinker in his own right, who gave a personal stamp to everything he wrote. He was important to Westerners coming to Buddhism because he had experienced the same struggle they were going through, the attempt to reconcile it with their own tradition. Watts had learned to think and write in the rigorous tradition of the British public school, where clarity and logic were at a premium, but in his heart he was a mystic, and he had a unique ability to render mystical experience in lucid prose. He wrote about timeless subjects, and to me his work is as alive today as when he wrote it.

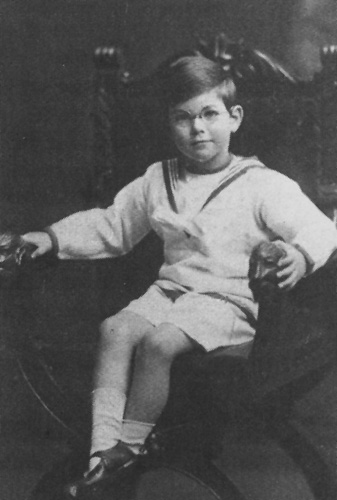

From early in his life, Alan Watts’ revulsion with things Western—with what he called the “boiled beef” culture of Great Britain—was as important as his attraction to the East. He was born in 1915 at Chislehurst in Kent, England, the much-awaited child of a middle-aged couple, and raised in the slightly unusual situation in which his father was the loving accepting parent and his mother the lawgiver. Almost nothing his son ever did seemed wrong to Laurence Watts, who—when Alan was 15 and declared himself a Buddhist—joined the Buddhist Lodge himself and became an active member. It was Emily Watts who was the difficult parent for Alan, who did not seem attractive and warm to him, who obviously loved him but was not physically affectionate. It was also she who practiced the dour form of fundamentalist Protestantism in which he was raised.

His parents wanted the best for their son, and at considerable sacrifice sent him to public (what for Americans would be private) school. He became a weekly boarder at the age of seven and a half, and he soon came to hate the school and its whole method of instruction, its ritual floggings, tasteless food and binding uniforms (he would still be railing against British food and clothing at the end of his life). He also missed the company of girls, who had been important companions for him. He longed for an authentic mentor rather than an authority figure who crammed learning into his head, and all his life he was drawn to a certain kind of cultured, sophisticated person with a light touch, a gaieté d’esprit. The renegade, playful Zen masters he was eventually drawn to—those on the fringes of the tradition—were such people. If he always distrusted a heavy, disciplined approach to life, it was because he’d had a large dose of it early on.

Watts was also alienated from his surroundings by his working class origins, and felt the stigma of being a scholarship student. He was a solitary, sensitive boy who read widely on his own and was disgusted with the narrowness of his religious instruction. He was particularly disappointed when he was unmoved by the ritual confirmation ceremony. When he was just a teenager he became interested in the writings of Lafcadio Hearn, who had travelled in the East. Watts, who had always enjoyed the lightness and space of Asian art, especially admired Hearn’s Gleanings in Buddha-Fields, and in the grand tradition of disaffected youth he abruptly declared his independence by writing off to London’s Buddhist Lodge and proclaiming himself a Buddhist.

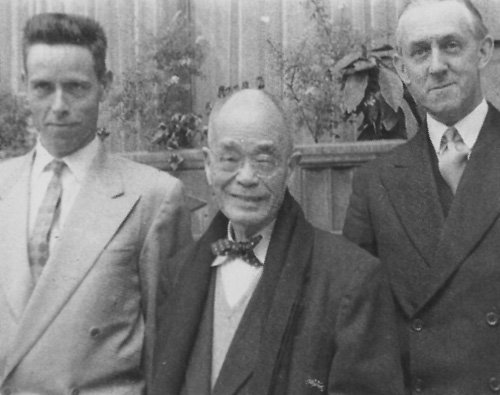

Christmas Humphreys, the head of the Lodge, was the kind of urbane, intelligent person the young Watts admired, and became an important mentor for him. It was through Humphreys that Watts met D.T. Suzuki, who would be his primary teacher of Zen (and who, like Watts, was also accused of being a popularizer and dilettante). Watts’ first book, The Spirit of Zen—composed when he was nineteen—was largely a summarizing of Suzuki’s work, though it also laid out themes that Watts would spend the rest of his life developing. By the time he wrote that book he was already working as a freelance writer; in his exam for a university scholarship he had written his answers “in the manner of Nietzsche” (whatever that might be) and failed to qualify. He would remain an autodidact and free spirit all his life.

It was shortly after the publication of The Spirit of Zen that Watts met the woman who was to be his first wife, a young American named Eleanor Everett, whose mother, Ruth, a serious Zen practitioner, later married the Japanese teacher Sokei-an Sasaki. In the repressive Britain of the early forties, Watts had yearned after sexual experience and finally he found it with Eleanor. She was just eighteen, and pregnant, when the twenty-three-year old Watts married her. There was a war on, and Watts—a lifelong pacifist—had no wish to fight. The young couple took off for the States. It was a fortuitous move in more ways than one, because Watts’ work would always be better received here than in his native Britain.

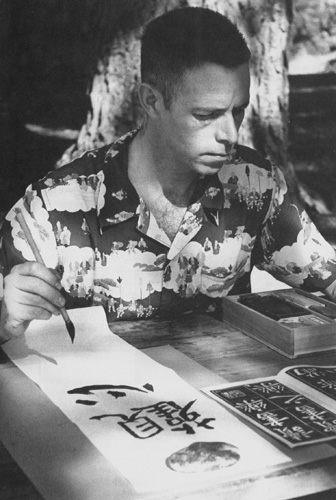

It is true that Watts never underwent—or particularly believed in—rigorous Zen training; his spiritual practice, as with that of D.T. Suzuki, was to some extent his vast scholarship and his writing (though Watts did practice calligraphy, archery, and other Zen activities). Rather than taking to the more rigorous and methodical Rinzai school, he inclined toward the Soto school, with its belief that we are already buddhas, and it is hard to read his writing without feeling that—despite his playful manner—he was a genuine mystic with a deep conviction in the ideas he expressed.

Two early experiences were vital, one when—in his studious way—he was sorting through various approaches to meditation and finally just threw them all out and sat; the other when he was struggling to stay in the present and Eleanor made the obvious but startling statement that we are always necessarily in the present, even when dreaming of the past or envisioning the future. Watts’ reaction on both occasions was the same:

Quite suddenly the weight of my own body disappeared. I felt that I owned nothing, not even a self, and that nothing owned me. The whole world became as transparent and unobstructed as my own mind; the “problem of life” simply ceased to exist, and for about eighteen hours I and everything around me felt like the wind blowing leaves across a field on an autumn day.

This experience of “cosmic consciousness” was the basis for all his work.

It was while he and Eleanor were living in New York that Watts made the somewhat bizarre decision to become an Episcopal priest. He had been studying and writing, leading an interesting life, but was essentially living off his well-to-do wife. Eleanor especially felt the strain of those circumstances, and during a period of depression, though she shared her husband’s Buddhist convictions, had wandered into St. Patrick’s Cathedral and experienced a vision of Christ. Watts never felt he was abandoning his Eastern convictions, but had come to believe that there might be a way to reconcile the two traditions, moved in part by the parallel between the Christian conflict between faith and works and a similar split in the Mahayana tradition between Pure Land practice and Zen meditation. He was also, quite simply, a man with deep spiritual convictions who was looking for a way to make a living in this country.

He had no university degree, but found a seminary that would admit him on the basis of his astonishingly wide reading. He became a chaplain at Northwestern University and for five years had what sounds like an extremely exciting and interesting—if not entirely orthodox—ministry. He introduced incense into Sunday services, for instance, along with Gregorian chant and Renaissance polyphony. He also wrote a book of theology, Behold the Spirit, that was widely hailed in Christian circles. One Episcopal reviewer said it would “prove to be one of the half dozen most significant books on religion published in the twentieth century.”

But by 1950 Watts’ marriage was in trouble. Both he and Eleanor had been sexually inexperienced when they met, and the times were also repressive. When Watts revealed a few facts about his sexuality—that he had masturbated frequently since his youth and sometimes stimulated himself with fantasies of flagellation—Eleanor was horrified, as she eventually stated in a somewhat bewildered letter to Watts’ bishop in Chicago. (Watts would write in a veiled way in his later books about erotic submission, a subject that he seemed to understand quite well. He believed it had less to do with guilt and punishment than with an uptight person’s wish to let go of his tensions. He also wrote about the way that pain could become a kind of ecstasy. Watts’ erotic life was not really at variance with his spiritual life, which also involved a gradual process of giving in and letting go.) Eleanor was also—perhaps more justifiably—concerned when he spoke of his attraction to coeds. The situation sounds all too familiar: an academic husband who was vital and alive in his work, surrounded by young women who found him attractive; a wife who did not have work of her own, who was not entirely happy staying at home with her two daughters, and who was often depressed.

When Eleanor grew enamored of a man ten years her junior, Watts, desiring freedom for himself, allowed her young lover to move in. That response might not have been so unusual fifteen or twenty years later, but in 1950 it must have been a shock—particularly since Watts was a man of the cloth. Their attempt at freedom didn’t save their marriage, however, and Eleanor had already given birth to her young lover’s son by the time she had the marriage annulled on the grounds that Watts was a “sexual pervert.” Knowing the scandal would drive him out anyway, Watts left his position at Northwestern and resigned from the priesthood.

Watts’ situation at that point seemed desperate. He had lost not only the wife who had often supported him but also his career. Shortly thereafter, however, he married a woman named Dorothy DeWitt and retained custody of his daughters. In these circumstances, he was lucky to meet Joseph Campbell, who not only became a lifelong friend but also helped him obtain a grant from the Bollingen Foundation.

Watts and his new wife traveled to San Francisco, where Frederic Spiegelberg was then founding the American Academy of Asian Studies. It was not really an academic institution, but as he describes it in his autobiography, it was:

concerned with the practical transformation of human consciousness, with the actual living out of the Hindu, Buddhist, and Taoist ways of life at the level of highest mysticism.

Among its students were poet Gary Snyder, the later Yoga guru Richard Hittleman, and the two founders of the Esalen Institute, Michael Murphy and Richard Price. Watts worked at the Academy for six years, four as its head. He was probably out of his element as an administrator, but there can be no doubt that his experience at the Academy had a strong influence on his later writing.

It was at the end of his stay there, in 1957, that Watts published his most famous and successful book, The Way of Zen. Much more compact an introduction than the voluminous work of D.T. Suzuki, Watts’ book moves through a history of Buddhism as well as the theory of Zen. It is surprising, looking back, that so scholarly a performance could have been so popular. Watts does perhaps emphasize the discipline of practice too little, almost makes it sound as if one can become a Buddhist simply by reading the book—which must have been its appeal to the hordes of hippies who carried it in their backpacks through the sixties—and it definitely inclines toward sudden illumination, reflecting Watts’ prejudice and Suzuki’s influence. But he is especially eloquent on Zen and the arts, and his understanding of the way the practice relates to everyday life is profound and inspiring.

Throughout his work Watts hammers away at one central idea, essentially the insight of his mystical moments, that all of creation is one. Man’s feeling that he is an isolated being in an alien environment is a basic illusion that leads to many others: that nature is somehow a threat to us and needs to be controlled, that human nature is similarly a dark and dangerous force. In Nature, Man, and Woman, published in 1958, Watts points out that women have always been associated with nature, and therefore seen as an unpredictable force which needs to be subdued. He insists instead that we are all one, and that sexual relations are an opportunity to celebrate this oneness, to understand that all dualities—man and woman, yin and yang, even what we think of as good and evil—are opposite sides of a coin and require each other to exist. He believes Westerners have sex “on the brain” because it is their only form of ecstasy, their only chance to escape the feeling of separateness, and that a true realization of their oneness with everything would make specifically sexual needs less urgent. Sex would become not “the repetition of a familiar ecstasy, prejudiced by the expectation of what we know” but “the exploration of our relationship with an ever-changing, ever unknown partner.”

Psychotherapy East and West is the third book in what I see as essentially a trilogy, a five-year flowering of Watts’ life as a writer (also assembled in that period was the excellent book of essays This Is It). Its premise is that the Eastern ways of liberation have more in common with psychotherapy than with Western religion, and that therapy and spiritual practice share a similar technique, which he calls the counter-game: they both allow the practitioner to act on his delusions until he backs himself into a corner and sees through them. Watts felt that the theory of psychotherapy fell short because it never saw through the existence of the ego (even Jung did not, despite his sympathy for the East), and also because the goal of therapy is to bring the patient into a healthy relationship with society, ignoring the possibility that society itself is sick (and the patient’s illness a form of sanity). Psychotherapy East and West transcends its subject with a lyrical final chapter which suggests that therapy should have “carried Freud’s thought to its full conclusion and learned to live without repression”; that Logos should be subordinated to Eros in our lives, not the other way around; and that liberation might ultimately lead to an adult form of what Freud pejoratively named the polymorphous perversity of the infant, an essentially erotic relationship with all creation.

By the early sixties, Watts was a major figure in the counterculture. He had left Dorothy, with whom he had had five children, and whom he claimed wanted to lead too conventional a life, and moved in with a woman named Mary Jane Yates, nicknamed Jano. They lived in a houseboat on the waterfront at Sausalito. Watts held seminars and gave lectures all over the country, and was much in demand. His writing took on a new free-flowing ease, but perhaps his most creative performances were the vast number of lectures he gave (available now from the Electronic University run by his son Mark). His talks naturally include repetition—he was constantly introducing himself to new audiences—but they are often brilliant, inspired and inspiring, and aid in an understanding of the writing. It is said Watts never prepared for them, but relied on his vast reading and innate abilities as a showman. This man who didn’t believe in the ego’s existence loved to have people pay attention to him—but perhaps that very belief was responsible for his ease.

Watts died in his sleep in 1973 at the age of fifty-seven. He had been a heavy smoker all his life, and an increasingly heavy drinker. Gary Snyder said that toward the end of his life Watts was putting away a bottle of vodka per day. The man obviously had huge flaws: he was never a faithful husband, and dismissed his child-rearing responsibilities with a few self-serving words. Yet in many ways his was a remarkable journey, from the young student who contacted the Buddhist Lodge to the independent scholar who helped introduce the East to a whole generation of Americans. If he is important to us—and he certainly has been to me—it is because he wrote about the shift in consciousness that many of us are undergoing, from a lonely isolated ego to an integral part of a vast ongoing creation. He didn’t—any more than we do—always live out of that realization, but he saw it clearly in his deepest moments, and spoke of it eloquently.

The people who adored Watts in the sixties and made him into a guru were astonished at his knowledge, which he had actually acquired through years of scholarship. Later they turned away, and sometimes spoke of him with disdain, because he hadn’t given them the “ultimate” answer that they were seeking. But Watts had never intended to be a guru, merely a philosopher with an endless sense of wonder at creation. If we don’t come to his work looking for something else, we can still sense that wonder. We won’t find an answer. Watts didn’t believe there was a question.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.