“You’re not who you think you are.”

The first time I heard Ram Dass say this, I felt something stir in me. It was the summer of 1974 and I was 20 years old. He was 43. It had never occurred to me that I was not my ego, but it seemed obvious once he said it. My obsessive thinking, according to his way of understanding things, was obscuring my soul. He had more to say on the subject, but the more theoretical he became the more my attention wandered. Nothing compared to the raw impact of that first proclamation: I was not who I thought I was. This seemed very true. Then who was I?

I am now 65 years old, and Ram Dass is almost 88. The comment he made, and the questions it provoked, have stayed with me over the past forty-odd years and guided me in my work with my patients. The ego takes refuge in the intellect, but as a famous psychoanalyst once said, “We are poor indeed if we are only sane.” Not knowing is better than pretending. As the ancient Buddhist text Dhammapada declared:

The fool who knows he is foolish is, let us say, wise.

The fool who thinks he is wise is hugely foolish.

In 1997, Ram Dass suffered a crippling stroke that left him paralyzed on his right side and challenged to find the words he needed to express himself. He was no longer who he had thought he was either. I visited him a year later, when I was well into my career. He greeted me with a chuckle.

“So are you a Buddhist psychiatrist now?” he teased me.

It took a long time to enunciate the entire sentence, but he did so with a twinkle in his eye. When I answered positively, he asked me another provocative question. He had trouble getting the words out, but I eventually understood what he was saying.

“Do you see them as already free?” he queried.

His question went right to the heart of what he had taught me all those years before. I did indeed try to see my patients as already free. My job was to help clear away the ego’s debris so that they could see it too.

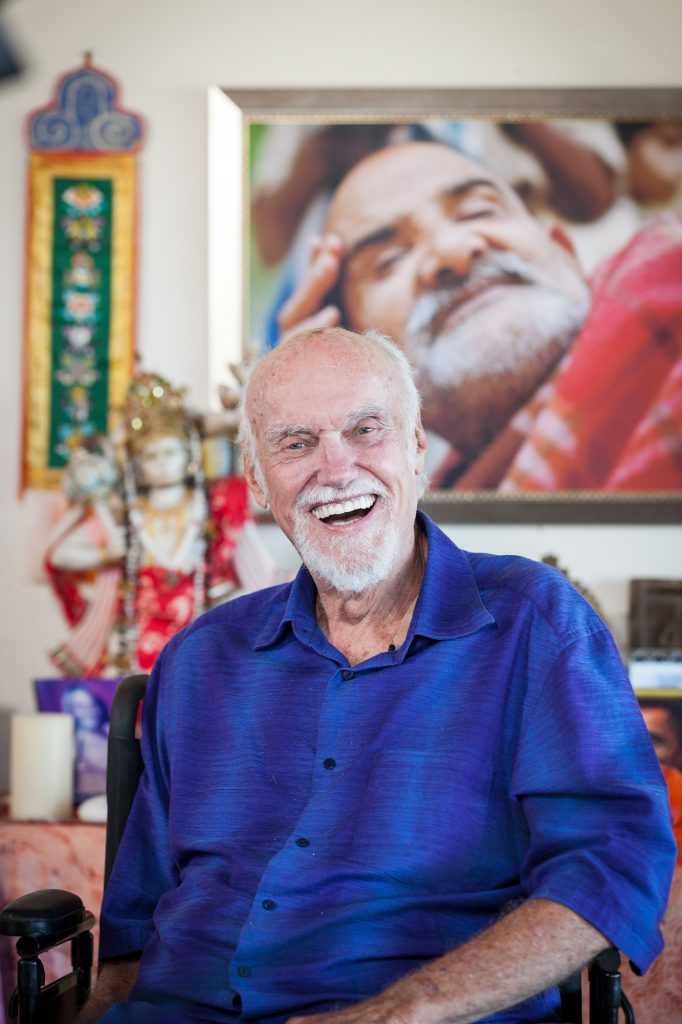

In April 2017, twenty years after our last encounter, I visited Ram Dass for several days at his home on the grounds of an old horse farm on the north shore of the island of Maui. On this occasion, Ram Dass did not question me about anything. I was waiting for him on the patio out behind his house at sunset, having just arrived from my New York flight. He came gliding down on a little elevator from his bedroom, the back door of the house flying open as he descended, and rolled out in his wheelchair onto the terrace in time for dinner. There was a smile on his face as he registered my surprise at his unanticipated entrance. Three white cranes had just swooped into the yard. His speech was much improved from the last time I had seen him, and he greeted me warmly.

“I’m spending much more time in here now,” he told me, pointing to his chest.

He was uncomplaining. He needed help from various attendants to move from his wheelchair to a garden chair, but his mood was chipper and he was clearly an inspiration to the people who were helping him. We had some good conversations about death over the next few days.

“Death is like taking off a tight shoe,” a spiritual friend had once told him.

“Soon I will be released from Central Jail!” his own guru had exclaimed after having a heart attack shortly before he died.

I told him how I had spoken to my father about the Buddhist view of death when he was 84 years old and newly diagnosed with a silent but malignant brain tumor. My father, a physician and professor of medicine with no interest in any of my spiritual pursuits, was a scientist who did not believe in an afterlife. I had always avoided talking to him about Buddhism, but I suddenly realized I had advice I had never given. He was surprisingly receptive.

“You know the feeling of yourself deep inside that hasn’t really changed since you were a boy?” I said. “The way you have felt the same to yourself as a young man, in middle age, and even now? It’s kind of transparent: you know what it is, but it’s hard to put your finger on it. You can just relax your mind into that feeling and ride out through it. The body comes apart, but you can rest in who you have always been.”

As we were sitting at the dinner table with the members of his household after this exchange, Ram Dass pointed at me and said to the others, “He’s . . . he’s . . . the real thing.” I had been somewhat nervous about visiting for such an extended time (I was there for three days in all), not wanting to impose on him, but his comment made me relax. I was very glad to feel his approval.

The next morning we took an expedition to the ocean for a swim. It was raining, but Mondays were beach days and the weather app promised that it would be sunny on the other side of the island. The weekly swim was a tradition I had heard about before I arrived, but I could not really envision how it was going to happen. Still, things unfolded smoothly. Six of us piled into two cars, Ram Dass sitting in the front of an SUV with his friend driving him. I sat in the back and listened as the driver played a recording of Ram Dass giving a lecture sometime in the 1970s when he still had his golden tongue. I remembered how enthralled I had been by his storytelling.

“Did you write that stuff out beforehand or just improvise?” I asked him. “The narrative is so well-constructed.”

“Improvised,” he responded with a hint of pride.

“How did you learn to do that?” I asked.

“I used to listen to my father giving speeches for Jewish charities,” he answered, and we laughed and laughed.

When we got to the beach, things moved quickly. The sun was shining and the ocean beckoned. Ram Dass was transferred from the SUV to a makeshift wooden wheelbarrow, a wet suit was maneuvered onto him, and he was wrapped in a life vest. He lay in the wheelbarrow grinning as he was wheeled into the ocean. I was already there, swimming into the oncoming waves, my first taste of the warm Hawai-ian waters. I turned just in time to see him being dumped out of the wheelbarrow. I had assumed he would just rest in the wagon and let the sea wash over him, but I was in for a surprise. Floating in the water, supported by his life vest, Ram Dass was able to use his good arm and leg to paddle at will. Lying on his back, he propelled himself around, bobbing and weaving like a jovial old prizefighter. Without my being aware of it, 15 people or so had joined him in the water. I swam toward them. They were an assortment of aging Maui folks, mostly ex-hippies from the mainland by the look and sound of them, familiar types to me but no one I had ever met before. It became clear very quickly that this was a regular thing for them: they came each week around this time to join Ram Dass in the water.

We were indeed a pod of souls, liberated, for an interlude, from the confines of our egos.

I was struck by their shining countenances. When I had spoken earlier with Ram Dass about death, he had used the phrase “a pod of souls” to talk about the way friendship and love bound people together life after life. The phrase came back to me in the ocean as I looked from one person to the next. We were like a pod of souls in that sea, jostling about as the waves lapped around us. Ram Dass was very happy to be freed from the encasement of his beleaguered body. The other people were glowing too, and I was caught up in the shared enthusiasm. One man (“He’s a retired dentist,” Ram Dass whispered to me as I swam alongside him) began to call out a Hawaiian chant. I had no idea what he was saying, but the sound rang true and everyone sang a gusty response. The beauty of each of the swimmers hit me deeply. I don’t really mean they were physically beautiful—they were not especially handsome—but each one of them was stunningly lovely. I suppose it was the communal happiness that gave me that impression. I was caught up in it: the buoyancy of the sea, the lightness of our bodies, the sun’s warmth, and Ram Dass’s evident pleasure.

The next thing I knew, everyone was singing:

Row, row, row your boat

Gently down the stream.

Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily . . .

The simplicity of the song made me happy. It was perfect. Soft waves were ushering us toward shore. The group was singing the verses in a round. Ram Dass was paddling himself; the rest of us were rowing alongside him. The waves were gentle as a stream. And the phrase “Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily” came spinning off everyone’s tongues like one of those hoop-rolling games European children played after the war. We were indeed a pod of souls, liberated, for an interlude, from the confines of our egos.

Back on shore, Ram Dass was quickly whisked out of his wet suit. He made it clear that he was taking everyone to lunch. An empty Thai restaurant in a nearby strip mall awaited us. The proprietors had clearly seen this group—or one like it—before. They were overjoyed and set a long table for 20. I sat across from Ram Dass, and the gathering stretched out on either side. Everyone was back in his or her personality, and I began to question my earlier impressions of their beauty. There was much commotion as a waitress began taking orders for Thai iced tea. A few people did not want ice; others could not drink condensed milk; many preferred theirs without sugar, and a few asked for Splenda instead. Some people wanted hot tea while others wanted decaf. One woman asked the group to turn off their cell phones since their electromagnetic radiation worsened her arthritis. My judgmental thoughts, refreshingly absent during my watery sojourn, began to flow freely, and I was once again back to who I thought I was. I shook my head wondering how long this was going to last. With the possible exception of Ram Dass, who was more interested in his lunch than in the kvetching around him, we were all swimming in our egos now, myself included.

In the back of my mind the nursery rhyme was running on. I had been so swept up in the rowing and the stream and the delightful sound of the word “merrily” (from the Old English myriglice, meaning “pleasantly,” “melodiously”) that I don’t think I had bothered to finish the song in my head. But now I did.

“Life is but a dream.”

Ordering the iced tea had been difficult enough for the group: imagine what happened when it came to the soup. Ram Dass ate heartily, though. I was full of disapproving thoughts, but he didn’t seem perturbed by any of what was flourishing around him. Later that evening, as we were watching a repeat of Saturday Night Live, he remarked on how happy he had been in the ocean. “Yep,” he repeated several times. “Yep . . . yep, that was great!” And he nodded his head in the affirmative. Throughout my entire visit he was consistently upbeat. Despite the constraint and discomfort of his long-suffering body, I had the distinct impression that he was already free.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.