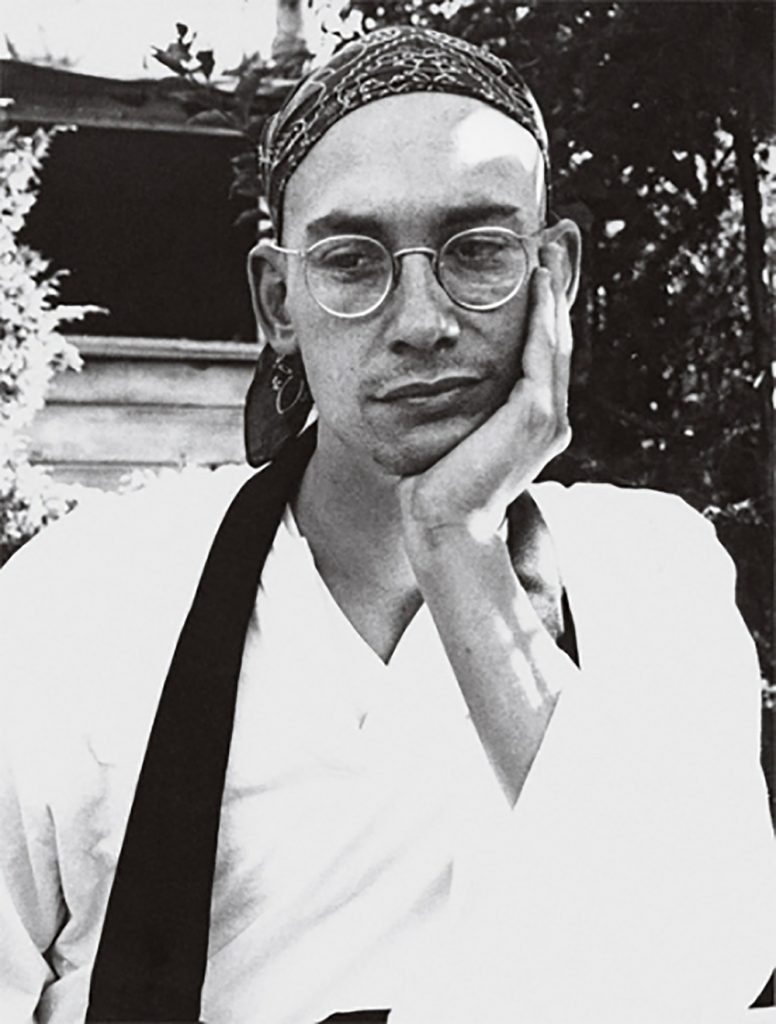

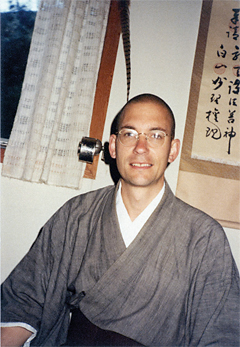

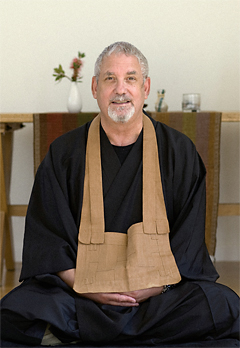

One thing that makes Lewis Richmond so interesting to speak with is that he is a person of so many interests. As a Buddhist teacher, an accomplished musician and composer, an author, a software engineer and entrepreneur, and someone whose curious and agile mind has garnered a great store of all manner of knowledge, he moves easily in conversation among diverse fields of culture and takes obvious enjoyment pursuing the unexpected turn toward wisdom.

Lewis is also interesting because he is genuinely fascinated by the experience of other people. This became abundantly clear to us at Tricycle when we invited him in March of last year to import to our community website a discussion that he began, and continues, on his blog Aging as a Spiritual Practice. Very quickly, the aging discussion became our most popular thread, thanks in no small part to the skill with which Lewis led it. His participation seemed not to be that of an authority figure, really, but of what in Buddhism is called a kalyana mitra, a spiritual friend. He guided the discussion gently—posing questions, sharing from his own experience, supporting what others had to say, contributing a timely quote, and so forth—and in that way, he helped the participants bring forth what is best in themselves.

Lewis is a Soto Zen priest and a dharma transmitted teacher in the lineage of Shunryu Suzuki Roshi (1904–1971), the founder of San Francisco Zen Center and Tassajara Zen Mountain Center, and the author of Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. Lewis is the founder and leader of the Vimala Sangha, in Mill Valley, California, and the Provost of Shogaku Zen Institute, a Buddhist training seminary. Recently he has also begun co-teaching, with Lama Palden Drolma, the founder of the Marin-based Sukhasiddhi Foundation, a series of workshops called Zen Heart Vajra Heart, which brings together the teachings of Zen and the Tibetan Mahamudra tradition. Lew’s book Aging as a Spiritual Practice: A Contemplative Guide to Growing Older and Wiser is scheduled to be published in Spring, 2012 by Gotham Books, a division of the Penguin Group.

—Andrew Cooper

You have had a long and varied life in Buddhist practice. What have been some of its key events, benchmark experiences, turning points, and the like? When I graduated from Harvard with a degree in music in 1967, my future was promising and clear: I was going to compose, perform, and perhaps teach music. But I walked away from my life. I didn’t really know what I wanted, but I knew that the course that was laid out for me wasn’t it. I returned to California, where I had grown up, and entered a seminary in the San Francisco Bay Area to prepare for a career as a Unitarian minister. One of my field assignments was to check out the Zen temple in San Francisco led by Shunryu Suzuki. Meeting Suzuki Roshi changed my life.

How so? Before encountering Suzuki Roshi, I didn’t know what I was searching for, but afterward, I knew that I had found it. It was authenticity. I would look at him and think, Okay, this is the real thing, and that touched me deeply. Later that year I dropped out of seminary to study with him, which I did until he died. During that time I was living, with my wife, Amy, in the rapidly growing community of the San Francisco Zen Center. Suzuki Roshi had ordained me as a priest. At his cremation I cried rivers of tears.

I continued my Zen training under Richard Baker Roshi, Suzuki Roshi’s successor. In 1974 I was installed as tanto [head of training] at Green Gulch Zen Temple, [in Marin County], one of our three practice centers. I was thirty years old at the time; I held that position for seven years.

Thirty was pretty young to take on the responsibilities and burdens of teaching Zen. We were all young in those days. Zen Center was an enormously exciting and innovative place to be at that time. We all felt we were creating something special and groundbreaking. I fully expected to live out my life there, serving Buddhism and fulfilling my vows as a Zen priest.

Why did you leave? The community went through a wrenching crisis in 1983, which culminated in Baker Roshi’s resignation as abbot. At its core were long-simmering questions and resentments about his leadership style, but I won’t go into any of the details here; it has been widely written about elsewhere. Shortly afterward, Amy and I left the Zen Center. We moved to Mill Valley, and I got a job (Amy already had one). I took off my robes, I let my hair grow, and we lived the life of ordinary folks, raising our nine-year-old son and going to work every day.

Most people thought that our departure from the community was due to the crisis of 1983. That was partly true, but it was also true that spiritually and developmentally I was ready to leave. I felt a need to take the carburetor of myself apart and reassemble it piece by piece, so I could figure out what had actually happened to me through those fifteen years of Zen practice and residential spiritual living.

Would you say that you once again walked away from the life that was laid out for you? Yes, I would. And as when I graduated from college, the change of direction had to do with a search for authenticity. After Baker Roshi left, I was one of the most senior priests in the Zen Center community, and I was close to completing my studies for dharma transmission, so there was a clear expectation shared by many people of the course my life would take. My leaving was confusing to some, upsetting to some, and I think generally controversial. But it was something I had to do. I walked away from my career in music because it didn’t feel authentic, and then I walked away from Zen Center because my life there had ceased to feel authentic.

I wanted to live an ordinary life as a householder, which I did. At the same time, I continued my study of Buddhism, especially in traditions other than Zen, such as Vipassana meditation and Vajrayana. I wanted to know what Buddhism looked like in other guises.

This “ordinary” life took an unexpected turn in 1985, when doctors found a cancerous tumor in my abdomen the size of a football. For the next year I lived the life of a cancer patient. The chemotherapy and radiation treatments made me sick as a dog, and even though I was able to return to work, my health was compromised for several years afterward.

For a while, I thought I was done with my priest vows, but over time I discovered that my vows weren’t done with me. Slowly, I edged my way back into teaching; I started a small sitting group in town and began to do some writing. I was especially interested in the contrasts between my life in Zen and my life as a business person. Over time I came up with a book idea that connected my years of Zen training with my experience in the corporate workplace. The book, Work as a Spiritual Practice, came out in 1999.

Just after the book came out, life handed me another rude shock. I fell ill and soon was in a deep coma that my doctors did not think I could survive, let alone recover from. I had viral encephalitis, a devastating and often fatal illness, and when I awoke after two weeks I had brain damage and a slew of other disabilities. It took me three or four years to fully heal. Out of that experience, I wrote my second book, Healing Lazarus, which described my coma visions, my illness, and my slow recovery.

It sounds like this time your life walked away from you. This illness totally changed my life. As a software developer, I had made my living with my brain. Being smart and capable was central to my identity, and suddenly that was all snatched away. When I awoke out of my coma, I was like a newborn baby. I could barely move; seeing, hearing, and thinking were all difficult. I had to learn to stand, walk, eat, and perform basic bodily functions all over again. For weeks I was unable to talk— that was especially hard!

Essentially, I had to reboot my whole life, including my life of Buddhist practice. During the early stages of recovery, I felt I had lost most of my practice resources; I couldn’t sit, meditate, or concentrate. So I chanted the nembutsu—the recitation of the name of the Buddha of the Pure Land, Namu Amida Butsu—asking Amida Buddha to help me. As time went on, I realized that not only had my practice been helping me all along but that something had happened while I was in the coma that had completely changed me. During the coma, I was totally unaware of the outside world. I had no body and no sense organs—just consciousness. I was fully conscious and awake the whole time. I went to the edge, and when I came back, I was different.

This reminds me of a question we asked a number of people to respond to several issues back: “How has a mistake, shortcoming, or misfortune enriched your Buddhist practice?” Without the misfortune of my illnesses I would not be able to teach in the way I do today, which includes advising and counseling people about illness and loss. So in a dharmic sense, my illnesses were also gifts. The encephalitis brought me to my knees; but in Buddhist practice, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. I got to find out what is really important, whether we’re talking about Buddhist practice or life in general.

When you take everything away, what have you got? That was the situation I had to work with. Having had everything stripped away, I understand that Buddha-mind does not depend on our capacities. The engine of practice is always there going. I unlearned a lot.

Sometimes when I’m asked to describe the Buddhist teachings, I say this: Everything is connected; nothing lasts; you are not alone. This is really just a restatement of the traditional Three Marks of Existence: non-self, impermanence, and suffering. I don’t think I would have expressed the truth of suffering as “you are not alone” before my illnesses, but now I find that talking about it that way gets at something important. The fact that we all suffer means we are all in the same boat, and that’s what allows us to feel compassion.

In addition to authenticity, do you discern any other themes that have provided continuity as your practice has assumed different forms? Yes, I can think of two. One has been a search for a universal and nonsectarian form of wisdom that can be made widely accessible and available to all people—priest and layperson, young and old, rich and poor, Asian and Western. I think this was Suzuki Roshi’s vision in coming to America. He saw Buddhism as an innate human treasure and as fundamental as breathing. He was curious, broad-minded, and willing to try new things in order to make Buddhism most approachable. But he only started a process that I believe he fully expected us, his disciples, to carry forward in ways he could not have foreseen.

The other theme begins with the recognition that we are in a time of planetary crisis. The core Buddhist teachings of interconnection, selflessness, and universal compassion are a most appropriate medicine for this crisis, I think. Buddhism is not just for inner transformation; it is for our common survival, and we Buddhists all need to do what we can to apply what is best in Buddhism to help heal our world.

Let’s take these two themes a little further, beginning with the idea of presenting Buddhism in a way that is approachable and widely accessible. This runs counter to how Zen has operated historically, where, like other meditation sects, its practice has generally been the province of a very small, often elite, monastic culture. In fact, making Buddhist practice universally available was specifically the intention of Honen [1133–1212] and Shinran [1173–1262], the founders of Japanese Pure Land Buddhism, and Nichiren [1222–1282], yet they are barely given attention by most meditation-oriented Buddhists in the West who might well support that very goal. That’s an interesting point. Suzuki Roshi used to say that Zen in the West would fit neither the traditional categories of priest nor lay practice, which is an idea that originated with Shinran. I think in coming to this country, Suzuki Roshi wanted to plant the seeds of dharma in fresh ground, so that something new could develop. Of course, it can’t all be about innovation; there has to be a real relationship to one’s tradition as well, which he also emphasized. You need a kind of dynamic tension between the traditional way and trying new things. I think that most of us who have been at this for a while are working with what that means. Neither priest nor layperson is simply where we are, and I’m just trying to express that in the particular flavor of the Suzuki Roshi lineage.

Regarding the second theme, while it is seems evident that interconnection, selflessness, and compassion are good medicine for our poisonous times, it is also true that Buddhism has historically had little to say—and usually nothing to say—about how these values are to be applied to social and political systems. In other words, Buddhism may indeed have much to say to our current crises, but doesn’t it also have much to learn about how to go about saying it? That’s right. In terms of relieving the material ills and injustices of society at large, Buddhism doesn’t have a particularly distinguished track record. Buddhism does have a lot to learn about addressing the social and political sources of suffering, and where is it going to learn it? Well, from us.

Look at some of the areas where Buddhism has had considerable success penetrating the mainstream of Western society—for example, pain management, mental health, death and dying, and neuroscience. In each case, Buddhism became a resource in a field that already existed and is making a substantial contribution to each of those areas. Similarly, Buddhism can be a resource for existing disciplines, groups, and movements confronting different aspects of our planetary crisis. Buddhism might not have a lot to offer in the way of political or economic analysis, and in fact may have a lot to learn. But it might have much to say about how ecological or social justice concerns are grounded in fundamental wisdom about the nature of how things are, and it might offer guidance in how to put that wisdom into ethical practice.

You came to Buddhist practice young. Over the decades, what in Buddhism have you changed your mind about?When I started practicing, I assumed, as many of us did, that the forms and methods of Asian Buddhism, just as they were, would lead us forthwith to enlightenment. All we had to do was practice them. Now my view is that wise and deep though these methods may be, the Western psyche also needs its own transformative approaches. I find the distinction in Tibetan Buddhism between absolute and relative practice useful here. The absolute practice of pure meditation is beyond culture, but the relative practices that develop compassion and transform ego may need to be more culture-specific.

The psychologist John Welwood, who has long been at the forefront of exploring the relationship of Buddhist practice and Western psychotherapy, identified this problem many years ago with his term “spiritual bypassing.” The superhighway of meditation practice alone can’t be a pretext for bypassing essential ego work; we also must traverse the local roads of personal and interpersonal transformation. This could be through psychotherapy, relationships and intimacy, group dynamics, learning about emotions, and so on.

In other words, buddhanature is the same for everyone, but ego-nature is not.

There is a subfield of anthropology, often called psychological anthropology, that examines the specific ways the ego, the personality, the sense of being a subject, are constructed in different cultural settings. When one reads some of the literature, what is fascinating is seeing the degree to which the very sense of subjectivity is culturally formed. It could be a long time before we grasp the implications of this for translating Buddhism across cultures. I think it may well be that many practices developed in Asia might not be psychologically beneficial for Westerners for just that reason. When I left Zen Center, I felt like I had a bad case of spiritual indigestion, as though I had taken in something that I couldn’t fully break down. This idea of the ego structure being significantly conditioned by culture probably has a lot to do with this. It might also speak to a common experience among many longtime practitioners I know, including myself: the discrepancy between what the tradition says should happen as a result of practice and the reality of what actually happens.

In exploring the topic “Aging as a Spiritual Practice” through online discussions, what have you been learning? How have you been surprised? My original intention in launching my “Aging as a Spiritual Practice” blog and online discussion was to use the aging process as a teaching tool about suffering and impermanence. Aging is a natural dharma gate; we experience the teaching whenever we look in the mirror.

What has surprised me is how rich the topic is. Impermanence and loss are just one part of it. Certainly people have eloquently shared their experience of the death of a spouse, illness and disability, depression, disappointment, and being disrespected or ignored in public. But there have also been great expressions of freedom and insight. People talk about how liberating it is not to care what other people think anymore, about the freedom to know what you want to do and just do it. Gratitude and appreciation are important themes, too—the joy of grandchildren, the peacefulness of a garden, the beauty of a sunset, the thrill of just waking up in the morning. The young don’t have these kinds of experiences, at least not in the same way. They seem to ripen with age.

I think maybe life is an acquired taste. Aging practitioners also describe the many ways their practice has had to change as they have grown older—not just physically, but also emotionally and energetically. None of us has the stamina we once did; some of us are losing our mental acuity, making it harder to concentrate or meditate. What is an appropriate practice as we grow older?

People do live longer now. I’m thinking that Buddhism needs to offer a young person’s practice—rigorous meditation, retreat, monastic life, and so on—and then an older person’s practice, emphasizing teaching, mentorship, care, compassion, and focusing on what is really important. It may take a village to raise a child, but it takes a whole lifetime to raise a buddha.

Once, when someone asked Suzuki Roshi why we sit zazen [Zen-style sitting meditation], he answered, “So you can enjoy your old age.” At the time we thought he was joking. Some joke! As we are now finding out, it’s really hard to enjoy your old age sometimes, but a lifetime of practice helps. You can get through a lot of life’s problems without a spiritual practice, but when you face your own mortality, you need a foundation in the deeper things.

You are the head teacher of the Vimala Sangha, a lay community named for the legendary enlightened layman Vimalakirti. Do you see lay practice in the West as a complement to monastic practice, as a necessary adaptation in a culture that, for any number of reasons, is not yet ready for a robust monastic way of life? Or is lay practice something sufficient unto itself, with its own footing, logic, and perspective?First of all, even though I lived in a spiritual community and did intensive monastic-style practice, I was married the whole time. Japanese Zen has its rather unique tradition of married priests, and that was the form of my practice. I have great respect for traditional celibate Buddhist monks and nuns, but I don’t pretend to have ever been one.

It is true that Buddhism has come down to us as primarily a monastic tradition. It is also true that monks have been the primary scribes, authors, and record-keepers of that tradition. There is almost nothing from laypeople. Yet there were always thriving communities of laymen and laywomen in every generation of Buddhism. What were their practices, where are their voices? The very existence of the Vimalakirti Sutra suggests that those voices were there, and they were strong.

I love the character of Vimalakirti because he lived the life of a fully engaged person of wisdom. He went to sporting events and bars, he had riches. He managed a large house with servants, he had a family and children. He ran for political office, he taught in the schools. He also had an inner practice as a renunciate that allowed him to enter all of these situations and yet remain untouched and unsullied by them.

Vimalakirti was preeminently a bodhisattva, a master of skillful means working to liberate beings everywhere he went. I think today we need bodhisattvas of many stripes, people who are able to put the bodhisattva vows into action in many settings. Lay practice might allow people to develop a wider set of skills for doing this. In that regard, this could be, for Buddhism, the laypersons’ time. Not that monastic forms are no longer important, but “engagement” seems to be the new watchword for Buddhists, and lay life may well better lend itself to that than monastic life.

For you personally, how do you connect the legendary figure Vimalakirti and your flesh-and-bones teacher Suzuki Roshi? Vimalakirti and Suzuki Roshi are my two main inspirations. There have, of course, been many others, perhaps the most important of whom has been Thich Nhat Hanh. In any case, I think of Suzuki Roshi’s teaching as having two main aspects: zazen and life itself. One way to describe the second aspect is simply to use the title of Zen Master Dogen’s famous essay Genjokoan, which literally translates as “actualizing the fundamental point” and means manifesting zazen presence in everything you do, confronting the present moment with a completely open mind. This is what Suzuki Roshi meant by beginner’s mind.

What I’m getting at is that meditation is not the whole show; life itself is the show. Living a good Buddhist life is not a matter of the more meditation, the better. What is important is manifesting beginner’s mind.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.