This article is the last in a four-part series on what in Buddhism is called the “four sights” or “divine messengers.” Some traditional biographies describe these sights—an old man, a sick man, a corpse, and an ascetic—as what compel the Buddha-to-be to lead a spiritual life. The first part, “Taken Away and Given,” can be found in the Fall 2015 issue; the second, “The Body as Battleground,” in Winter 2015; and the third, “In the End,” in Spring 2016.

–The Editors

1

It is said that finally Prince Siddhartha could not divert his mind from the imminence of old age, sickness, and death. There was no one to alleviate his distress. Claustrophobia engulfed him. Again he left the palace, but this time he went alone and on foot.

As sunset fell, travelers disappeared from the roads. Merchants closed their shops. Farmers withdrew into their dwellings. The air grew cool. Birds sang their lullabies before hiding in the trees. And in the deepening night, the world and its great variety of life dissolved in darkness. Prince Siddhartha wandered through the shadows of farms and forests. Animals rustled in the underbrush. Monkeys moved through the upper branches of the trees. He heard men and women sighing in their sleep, moving restlessly in dream. He heard children cry out and old people groan. He felt time and decay and death moving like wind across the earth. The prince sighed and suddenly felt exhausted.

The sun began to rise. He watched as slowly the shapes and colors of the world began again to separate themselves from darkness. Again birds sang. Cattle mooed and water buffalo roared. Men and women emerged from their dwellings and resumed their labors. “Why?” thought Prince Siddhartha. “Why this endless struggling?” He sat beside the road in the shadow of a plain tree and wept.

After some time, a beggar in tattered robes approached him, carrying a gourd and walking with a staff. The man was young but emaciated; his eyes were bright and alert. He looked at the prince with detached curiosity but said nothing. Finally the prince grew impatient.

“Who are you?” he asked. “Where are you going?”

“Young lord,” the beggar replied, “My name is not important since I do not seek companionship. I move from place to place, but I am not going anywhere.” The prince was struck by the man’s calm and asked, “Surely you have a family and once lived somewhere. How did you come to adopt this way of life?” The young man took some time to answer:

“As you well know, my lord, everything alive will soon disintegrate and die. Pain does not cease. We are imprisoned here. I renounced worldly goals and set out to see what, if anything, continues.”

The prince was deeply impressed by the man’s simplicity. He asked, “And so, sir, what have you found?”

“My lord, nothing endures, but mind never ceases seeking form.” Prince Siddhartha reflected on this.

He hesitated, then asked: “Is there a path beyond that?”

The beggar looked at the prince. Time stopped. Siddhartha heard the clatter of wings as a flock of blackbirds took to the air. He smelled the smoke of a wood fire. There was nothing to resist. Then the prince looked up. The young beggar had disappeared in the morning mist.

It was a day later when Prince Siddhartha returned to the palace. He went directly to his father, the king. He bowed. “Great King, merciful father, please grant the request I must make. I am determined to leave the palace. For the sake of all beings, I must find the path that leads to freedom from the world of birth and death.”

“Why do you think you can find something no one has ever found?” the king asked sadly. Prince Siddhartha could not answer. He prostrated himself three times before his weeping father and left.

As he passed beneath the shadow of great stone lintel of the palace gate, he paused. A gap opened before him. His past was behind. He had no idea where his next footstep would lead or what he would become.

2

Ours is a world of work unending.

That there might be some finality is not so.

Now and now, the undone must be re-done:

Inspiration must be restored

Discipline must be maintained,

The banisters and parasols must be repaired,

Dinner, breakfast, lunch must be prepared

And eaten.

Jewels must be polished, carpets cleaned.

And gold, which does not change or rust,

Must be counted, hidden, stolen, shaped and melted down

again.

Friends must be written, condolence calls made

And love letters, true love, friendship, kind thoughts all

nourished and renewed.

You believe, sitting as thoughts

Make you hope or squirm,

That it will stop?

That if you concentrate or relax,

Pure radiant space will sweep you clean?

You’ve read it, heard it, no?

But no, no, no, and no

So long as you, this world and you endure

The work remains ever, ever undone and ever, ever, ever

To be done again.

Now.

3

The first time I heard Trungpa Rinpoche give a talk, I went out of curiosity. I sat in the balcony at the back of a church and waited for more than an hour. Everyone sat quietly. I didn’t know if they were meditating or just waiting. Then there was whispering. People began to wander in and out of the chancel, returning to sit quietly, then stirring around, then sitting again. Eventually there was an expectant buzz. A group of nondescript young men and women bustled importantly onto the platform where Rinpoche would speak. They placed a vase of flowers and a carafe of what I later learned was rice wine on a small table to the right of a rather shabby brocade upholstered chair.

Now Rinpoche limped in and sat down. He was small, stocky, and evidently crippled. His movements were slow and considered. He wore an unostentatious jacket and tie. There was nothing exotic about him. He could have been Korean or Hawaiian. But as he looked slowly at each member of the audience, his gaze was by turns indifferent, mischievous, intent, and somehow a little menacing. Seated so far back, I was relieved that he could not notice me.

Rinpoche began to speak. His voice was high, a little strangled. He made no effort to flatter or charm his listeners. He scratched his neck, drank from his cup, took long pauses, smiled, drank again, resumed talking. Each gesture was uncalculated but somehow completely conscious. I was mesmerized.

As if the space around him was fluid like water, Rinpoche’s every movement unfolded and rippled in the air. When he lifted the cup, I could sense him feeling its shape, its weight; when he drank, he was aware of the temperature, the slipperiness, the taste of the sake, and when he swallowed, he followed its progress into his body. The way he put the cup down, lowering his arm slowly until the base of the cup touched the wood of the table, the small thud it made, the release of the cup’s weight from his hand, made each of the gestures in this ordinary continuum magnetic. I felt that I was in the presence of someone who was completely part of life.

He said something about people not stepping into life.

“You are perching on energy like a bird flitting from branch to branch.”

The talk made an even deeper impression, and much to my shock, I bumped into him as he was leaving the men’s room and I was going in. “How are you?” he asked. “Just fine,” I managed. And so I began my life as his student with a lie.

4

In ancient times, the legendary King Indrabhuti proclaimed:

O you who wander in the human realm,

On the paths of ordinary delusion,

On the path of those who simply hear the truth,

On the path of renunciants,

On the path of personal realization,

Or on any other path known thus far;

Whether you pursue methods of purification or union,

You struggle for liberation from bondage in samara’s

whirling coils.

But subtly,

You conceive of enlightenment as escape;

Conceive of the infinite expanse of wakefulness

As heaven and a final resting place.

I, Indrabhuti, tell you that enlightenment is not

beyond the world.

It is the primordial ground.

It is all-pervasive.

Unoriginated, it is the source.

Unceasing, it is extinction.

Without location, it is like space.

Because it is empty, it is the feeling of unreality.

Because it is the ground, it is the feeling of reality.

Because it is subtle, there is the experience of confusion.

Because it is unceasing, there is the experience of meaning.

Because it is non-dual, it is complete compassion.

Because it is compassion, it is the truth and the innate law.

Logic does not capture or penetrate it.

Renunciation does not purify it.

Meditation does not stabilize it.

Behavior does not expand or diminish it.

It is reality itself and is not an attainment of any kind.

Moving from realm to realm

By awareness, by vision, by living,

By caring for the well-being of all who live,

By loving them;

All this is the same as the light of the sun

Passing through clouds.

5

I dream I am on a retreat I have long wanted to make. I am sitting at a cave’s opening. I look out over a narrow valley. The pine trees look black, and I gaze at the trunks and branches of trees whose leaves have fallen lower in the ravine. Huge slabs of granite, gray and cracked, rise from the floor far below. I hear the racing creek at the bottom, but I cannot see it. A light snow begins: large puffy flakes, the first of the winter, emerge from the gray air with a faint hiss, float and fall, disappear below.

I dream I am wearing a rough wool robe and sitting on an antelope skin. I have set up a small shrine against the dry rock wall to my left. A table in front holds the two texts I will use for practice, my vajra, bell, and skull cup. Deeper in the cave is an old trunk with sacks of grain. A small fire flutters as air moves out from somewhere deep in the earth.

6

In sleep, I hear the purling of the stream fading in the air from far below. Outside, the cold breeze carries a hint of incense. Perhaps I am imagining it. All who have practiced here before me have left some momentum, a slender and enduring stream that is now carrying me. I feel overwhelmed. My teachers have drawn this stream into the world. It is carrying me.

I look out into the evening sky. I imagine myself hurtling through the air, the earth and sky spinning around me. Air rushing tearing at my arms and legs, pulling my hair ripping at my clothes. Exhilaration and terror. The swirling looming earth and the inescapable violent pain, unimaginable. Some transformation, end, and intensity beyond any mind.

7

Since the instant of your birth,

You are being transformed.

It is your path.

It is making you.

There is the solitude of one self.

One self is sitting in a room in shadow.

There is the life that is pulsing from within and pushing

Pushing out

Out into uncertain night,

Where a loving consort waits,

Where there may be an assassin,

Where the crickets are singing under the floor,

Where a child is dying alone,

Where a farmer is turning home exhausted,

Where there is no rice,

Where there is a wonderful book,

Where another man nearby has a great deal of rice,

Where a woman is giving birth,

Where a fox is biting the hen’s neck,

Where the god of thunder wakes,

Where the goddess in an apple tree spreads her legs,

Where a frog dives into the depths of a pond,

Where an old man drinks rice wine and waits,

Wondering if waiting to write corrupts the night,

Returning to sit in the shadows.

There is the chaos of meditation

Where there is the discomfort of solitude,

The waiting for a guest who does not arrive

The visitor one hears outside on the path,

Who refuses to answer.

8

Long ago, the great Indian teacher Kanha sang this song of the path:

When moving through reality, like space,

The desire to go anywhere

Is a ghost’s quest to reach the horizon.

Wishing to get to the juicy conclusion,

You’re a deer chasing the water-mirage.

You’ve been buddha from the very beginning!

Big mistake to become buddha again.

Why would you think

You can re-create the enlightenment of someone else?

9

In one of Trungpa Rinpoche’s early seminars, he talked about goal and path in this way:

“The goal exists in every moment of our life situation on our spiritual journey. In this way, the spiritual journey becomes equally exciting and beautiful, as if you are Buddha already. There are constant new discoveries, constant messages and constant warnings. Constant cutting down. Constant painful as well as pleasurable lessons. . . . It is a complete journey.

. . . It doesn’t have to be labeled ‘spirituality’ as such.”

10

When King Sudhodana had tried to dissuade his son from departing, Prince Siddhartha could find no way to explain. He could not capture the torrent of words and images that were passing through him. Time alone would make them appear. From teacher to student, from mouth to ear, the wordless would become an unending stream of moments, like a luminous white lotus, a lineage endlessly unfolding from the depths of space.

♦

Section 1 extensively adapted from The Life of Buddha, by A. Ferdinand Herold, trans. Paul C. Blum [1922], at sacred-texts.com.

Section 8 translated by Matthew T. Kapstein in Dohas and Gray Texts: Reflections on a Song Attributed to Kanha, www.academia.edu.

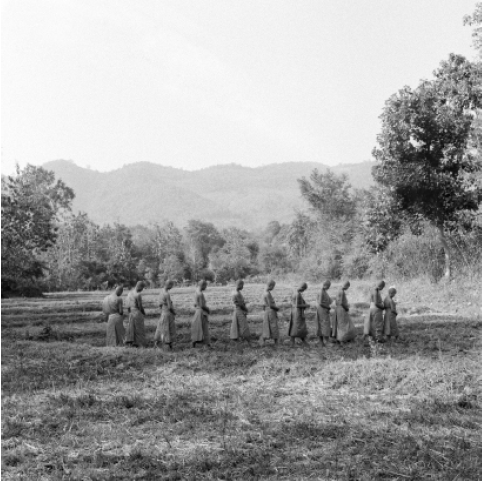

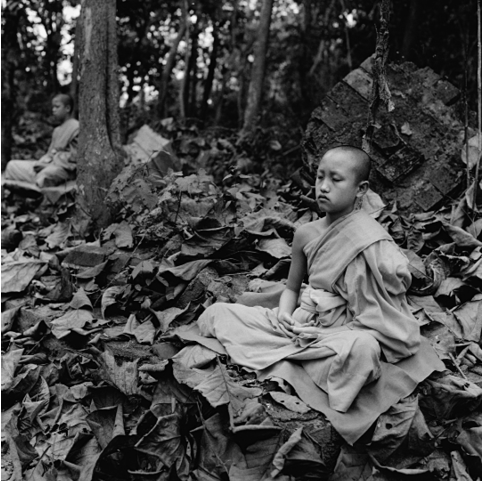

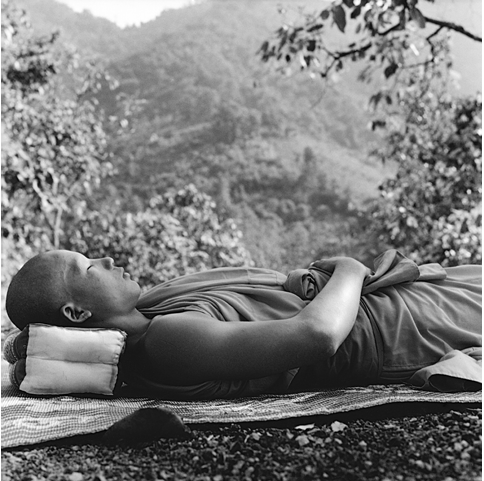

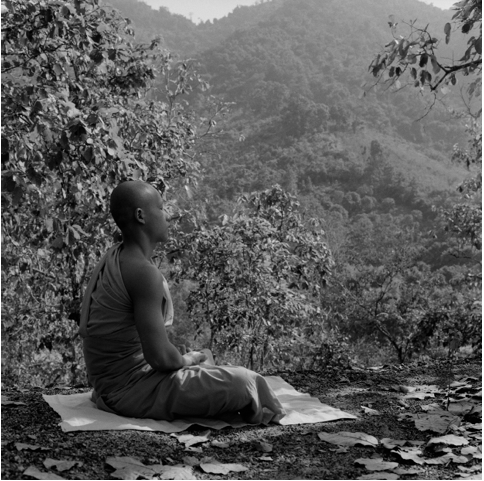

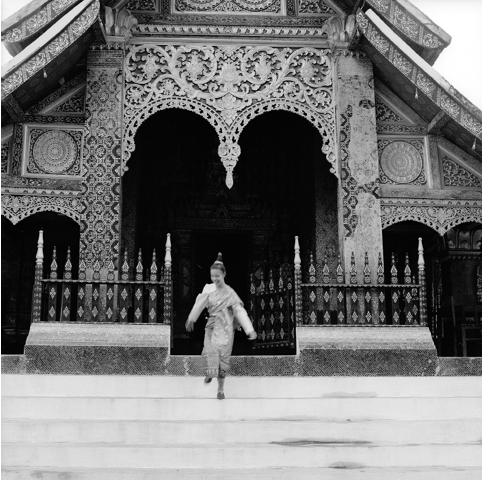

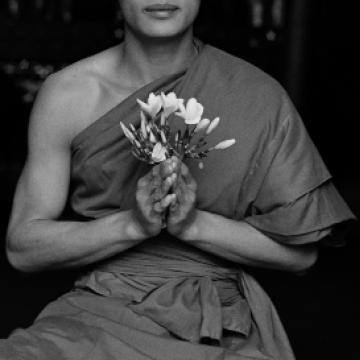

The photographs in this piece are from the series Laos: Sacred Ceremonies of Luang Prabang. Many appear in Hans Georg Berger’s latest book, My Sacred Laos, www.hansgeorgberger.de.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.