This is the second of a pair of Ancestors profiles about two 20th-century Buryat Buddhists: Lubsan Samdan Tsydenov, who established an independent Buddhist kingdom in the midst of the Russian Revolution, and his heir, Bidia Dandaron. The first installment, “Lubsan Samdan Tsydenov: A Vanished Buddhist King,” was published in the Summer 2018 issue.

In the diamond of awareness,

All display: true, delusory,

Lovely, agonizing,

Each a path of wakening.Spinning through seasons: birth and death,

Breath exhausts all it animates.In every instant wakening,

Something falls away.This is the inseparable body, speech,

and mind of Vajrasattva,

Appearing in all the realms of existence as

Yamantaka, Conqueror of Death.

Vajrasattva

a tantric deity seen as the personification of innate enlightenment.

Again we are looking into a tormented sea, swirling with fragments of papers, journals, whispered lies, beautiful visions, violent death, torture, desperate survival, petty viciousness, terror, ambition, rumor, idealism, myth, interpretation posing as fact. But within the seething murk, the roiling waves, we see rising from deep below, something, the outline of a miraculous being, luminous, gold, drawing us into the flood.

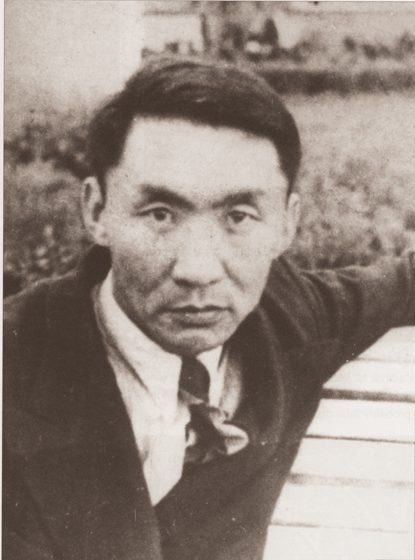

This is Bidia Dandaron, who lived in times that did not allow him the illusion that there was any path by which he could escape the immensity of pain inflicted in this world. He would find and teach a hidden way.

“Oh, the wonder of Vajrasattva,” Bidiadhara Dandarovich Dandaron exclaimed. He was not quite 60, but had broken an arm and a leg not so long ago. The injuries were barely healed when he was forced back on a work gang. It was his third and final incarceration; this time he was in a gulag at Vydrino on the southern shores of Lake Baikal. He was still teaching people who came to him in secret. He was a scholar renowned for his mastery of Buddhist and Western philosophy, but he now taught a path of Buddhist tantric practice entirely adapted to the brutality of the age. The world of monasteries, monks, and renowned teachers was completely gone.

Related: The Trials of Dandaron

Accounts of Bidia Dandaron’s life and that of his teacher, Lubsan Samdan Tsydenov, are somewhat haphazard, as one might expect after decades in which, throughout Buryatia, all Buddhist temples were destroyed, libraries sacked, and all who would have known about these men killed or scattered through the vast network of prison camps. Nonetheless, it is clear that Dandaron’s path began when his father brought him to one of the most courageous and profound teachers in the history of Central Asia: Lubsan Samdan Tsydenov.

Rations were barely edible, calculated to keep prisoners on the edge of starvation.

Bidia Dandaron was born in Kizhinga, Buryatia, on December 28, 1914. His mother was a dedicated Buddhist practitioner, the widow of a wandering lama, Dazarof Dandar. His stepfather was Dorje Badmaev, the closest disciple and dharma heir of the renowned Lubsan Samdan Tsydenov, sometime abbot of the monastery Kudun Datsan and a holder of both the Gelug and Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist lineages. Dandaron’s stepfather began teaching him from early childhood. When he was 3, a party of Gelugpa monks from Tibet came to inform Dandaron’s family that their son had been recognized as the reincarnation of Jayagsy Rinpoche, Tsydenov’s teacher and abbot of Kumbum Monastery in Tibet. They wished to take him to Tibet for training, but Tsydenov and Bidia’s stepfather felt that it was better for the boy to stay in Buryatia. The monks departed; monastic officials later recognized an alternative candidate.

Dandaron continued to live and study with his parents in Soorkhoi, where a small community of practitioners lived under Tsydenov’s auspices. During this time, a number of anti-Bolshevik armies, some little more than bandit gangs, crisscrossed Siberia and the Mongolian steppes, each trying to secure its own base to resist the Red armies who were taking over Russia.

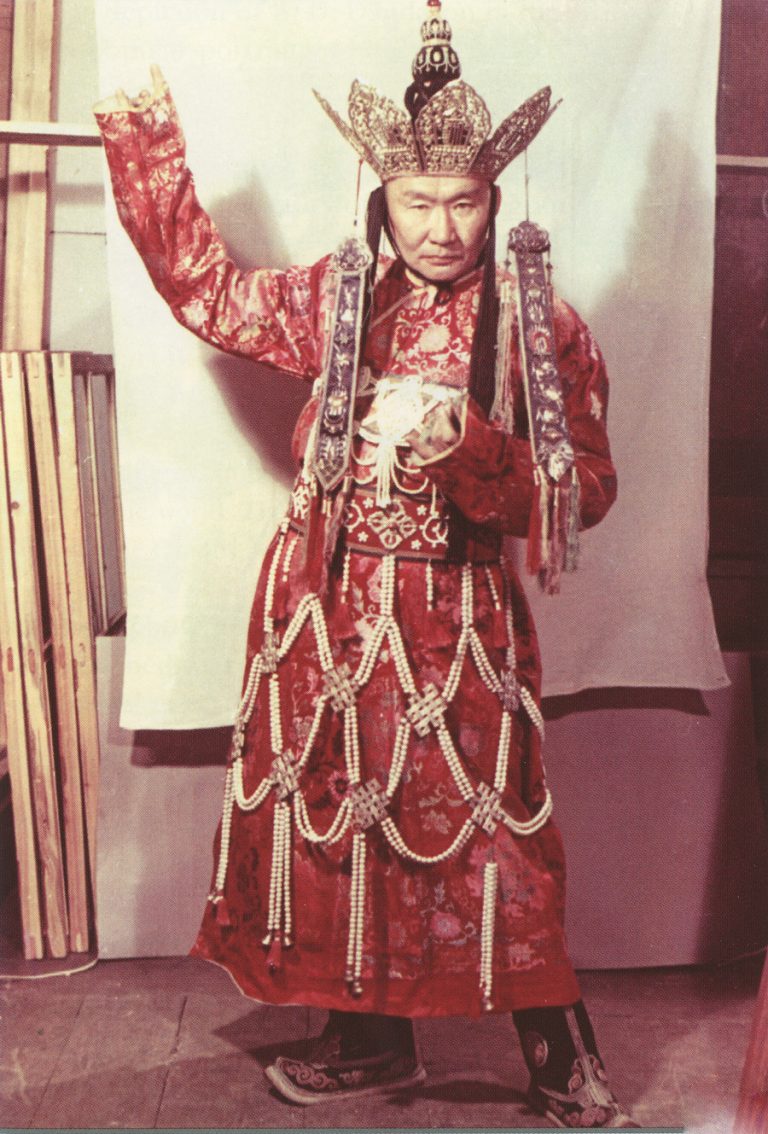

In 1919, in an effort to help 13,000 Buryat families who had requested his protection, Tsydenov took the extraordinary step of proclaiming a Buddhist kingdom under his rule as a chakravartin, or dharma king. His government contained strong Western influences. A constituent assembly was elected by popular vote, and all the government ministers were elected from that body. All laws were made in accord with Buddhist doctrine; nonviolence was the law of the land, and its people were exempt from being drafted into any of the surrounding armies.

Tsydenov, despite the death of Badmaev, his disciple and successor, in 1919, was able to maintain this kingdom for a year. Then he was taken prisoner by Ataman Grigory Semyenov’s agents and moved further into northern Siberia. In 1920, while still in prison, Tsydenov decreed that Badmaev’s son, Bidia Dandaron, should succeed to this title and throne. Soon after, the Soviets captured Tsydenov, and he was never seen again.

Dandaron was 7 when Tsydenov left, but he did not forget him, although he never pursued any claim to Tsydenov’s title. Apparently he and his mother moved to Ulan-Ude, the capital of Buryatia, where Dandaron continued Buddhist study and practice and at the same time attended the state secondary school, where mathematics, sciences, and, of course, communist doctrine made up a great deal of the curriculum. How proud his teachers must have been that someone with such a primitive background was capable of mastering the languages and scientific knowledge needed for acceptance into the Aircraft Device Construction Institute in Leningrad. There Dandaron studied aeronautical engineering from 1934 to 1937.

During this time, he got married and had two children. He also audited classes in Tibetan at the Oriental Studies Institute of Leningrad State University. The depth of his understanding and experience in Buddhist teachings as well as his openness to Western analytical methods made a great impression on many of the students and faculty members. He deepened his study of the Tibetan language with the distinguished Russian scholar Andrei Vostrikov, with whom he became particularly close.

In late 1937, toward the end of the great wave of Stalinist purges, Dandaron was arrested as a Japanese spy and an agent of an alleged “pan-Mongolian conspiracy.” This was part of the Soviet’s unrelenting effort to erase any religion that could serve as a focus for nationalist sentiment.

Shortly after Dandaron’s arrest, Vostrikov was taken into custody and executed. Dandaron was sentenced to a six-year term of hard labor at a camp in Siberia. His wife and children were allowed to accompany him, but she was released after several months. She had pneumonia and died, as did one of the children.

All of the forced labor camps in the vast Soviet Gulag system required that days be spent in heavy manual work such as mining, road construction, ditch digging, or forestry in the most extreme weather conditions. By night, prisoners were packed into bunks in wooden dormitories; the stench was overwhelming. Rations were barely edible, calculated to keep prisoners on the edge of starvation. There was no sanitation to speak of. Discipline was arbitrary and brutal. Violence was unceasing. Death rates were, as intended, high.

As one who managed to survive, the Polish-French writer Jacques Rossi explains in his “encyclopedia dictionary” The Gulag Handbook: “The Gulag was conceived in order to transform human matter into a docile, exhausted, ill-smelling mass . . . thinking of nothing but how to appease the constant torture of hunger, living in the instant, concerned with nothing apart from evading kicks, cold, and ill-treatment.”

Another survivor, the Russian author Varlam Shalamov, wrote, “All human emotions—love, friendship, envy, concern for one’s fellow man, compassion, longing for fame, honesty— had left us with the flesh that had melted from our bodies.”

“Dandaron is a hero, unburdened by the horizons of dogma.”

Dandaron lived under these conditions for six years. He was often tortured and permanently bore the scars inflicted by the back of a Cossack’s saber. Nonetheless, he found ways to continue his meditative and yogic practices, study books that were smuggled in to him, send and receive an occasional letter, and teach fellow inmates how to meditate despite the extreme nature of their situation. He was released in 1943.

The next five years were marked by a temporary softening of the government’s attitude toward religion. The Ivolginsky and Aginsky monasteries were reopened under the supervision of government agencies, although “wandering lamas” taught and performed ceremonies privately. Dandaron was able to renew some of his former friendships in both Leningrad and Ulan-Ude. He resumed his work translating texts, and small groups of Western and Buryat practitioners began to meet with him.

Dandaron was arrested again in 1948 and given a ten-year labor camp sentence. This time, the overall conditions were evidently not quite so harsh as during his earlier confinement. He also benefitted from the companionship of certain Buryat lamas and Western philosophers who had been swept into the government’s net. Dandaron considered himself particularly lucky to be able to study Kant while imprisoned with the Russian-Lithuanian philosopher Vasily Seseman and became increasingly interested in the conjunction of Western and Buddhist thought. He was also able to write a wide range of articles and commentaries, but most of these were intercepted and destroyed.

Dandaron now attracted disciples from Buryatia, Russia, Ukraine, Latvia, and Estonia, many highly educated in a wide range of subjects. These fellow prisoners became his most loyal adherents, and they became what was later called the core of the “Sangha of Dandaron.” He taught what he called “neo-Buddhism,” whereby he explored ways of combining Buddhism with European philosophy and science.

His group viewed practice and study not as an exterior preoccupation but as an investigation of the inner ways in which Buddhist practice and thought illuminated and were illuminated by their lives in the labor camp. It was, as Dandaron said, the collective karma they shared with the Soviet world as a whole.

In February 1956, Nikita Khrushchev gave his famous “secret speech” in Moscow before the 20th Communist Party Congress, repudiating the excesses of Stalin’s cult of personality in general and, more specifically, the mass imprisonments in the gulag. Within a year, Dandaron found himself rehabilitated and released.

He joked that “for a Buddhist journeying from one incarnation to another, it was very useful to be born in Russia.” He would add, laughing: “Note that I say a Buddhist and not Buddhists.”

In 1957 Dandaron renewed his contacts in Leningrad, but friends and colleagues were unable to find him a permanent position there. He was, however, able to find work at the Buryat Institute of Social Sciences in Ulan-Ude. There he worked with three other Buryat lamas to catalogue and oversee the preservation of the large number of books that had formerly been part of monastic libraries, most notably on the topics of the Tibetan Kangyur [collected sutras] and Tengyur [commentaries]. He traveled frequently to Leningrad and there, by a stroke of luck, met George Roerich, son of Nicholas Roerich, the famous painter and theosophical philosopher. George Roerich was, in his own right, a great and widely traveled Tibetologist, and the two began working closely together, producing a large number of scholarly papers. It was a great blow, both to Dandaron and to Buddhist studies in Russia, when Roerich died suddenly in 1960.

Nonetheless, Dandaron continued to produce studies in Buddhist religion and history as well as Tibetan-Russian translations of Buddhist texts. He also wrote essays exploring ways in which Buddhist concepts could enrich and develop Western philosophical and scientific thought, and reciprocally how Western thinking could find a place along the continuum of classical Buddhist concerns. These essays were privately printed and secretly distributed in samizdat form.

At the same time, a group of students continued to gather around him, some formerly from the camps, others from the academic world. Sometimes he would go to Leningrad, and sometimes the students would take the weeklong train ride to visit him in Ulan-Ude. Dandaron commented: “It’s not that students are coming to me in Ulan-Ude; it’s Buddhism that is moving westward.”

His tantric teaching at this time was focused on the practice of Yamantaka, Conqueror of the Lord of Death. Though these have always been secret teachings, Dandaron seems to have emphasized an approach in which all the bardos, all the transitions in life—dream, meditation, death, and rebirth, all the unending transitions in what we call existence and nonexistence— are each and every one a path of enlightenment.

In a talk printed in Moscow in 1970, Dandaron began with these words: “Our knowledge is limited by the boundaries of samsara and by the manifestation of nirvana, each of which has its own limits, namely the limits of our system of time and space and the physical world order in which we move. About such knowledge in any other time or era, we must admit that its substance and character are unknown to us.”

“Buddhism,” he said, “has neither place nor time nor epoch. Buddhism journeys on, unaware of peoples, countries, climates, revivals or declines, societies or social groups. This does not mean that Buddhism denies such things. Buddhism denies nothing. This means that Buddhism itself is not aware of them. Such things are not its concern.”

“Dandaron is bodhisattva-mahasattva. He is a hero,” said his student, the philosopher Vladimir Montlevich. “He was unburdened by the horizons of dogma. He tore that away. He also intuited the needs of our time, and in this he was exactly what he said: a neo-Buddhist.”

Dandaron had always been viewed with suspicion and dislike by members of the Buryat Communist Party in Ulan-Ude. He upheld traditions that they wanted to leave behind in their effort to find a modern identity. They expected him to show the Russians that people of the steppes were as capable as anyone of contributing to modern communism. But he had betrayed them. Late one night, young Buryat communists destroyed the stupas he and his followers had built in honor of his teacher, Samdan Tsydenov, and his stepfather, Dorje Badmaev. No doubt they were also behind the denunciations that led to Dandaron’s arrest and the charges that were laid against him in Leningrad in 1972.

Related: From Russia with Love

On December 27, 1972, Dandaron was tried in Ulan-Ude under article 227 of the Soviet criminal code. He was accused of leading a Buddhist sect that participated in “bloody sacrifices” and “ritual copulations” and of attempting to “murder or beat former members of the sect who wanted to leave it.” Further charges included “contacts with foreign countries and international Zionism.” In the end, most charges were dropped, but the contentions that the “Dandaron Group” held prayer meetings and had an illicit financial fund, and that Dandaron acted as “guru” to the group were accepted without proof. Four associates—Yuri K. Lavrov, the painter Aleksandr Ivanovich Zheleznov, Donatas Butkus, and the philosopher Vladimir Montlevich—were subjected to psychological examination, found to be mentally ill, and sent to psychiatric institutions (from which they were soon released). Dandaron was sentenced to five years’ deprivation of freedom under conditions of forced labor in a “corrective labor colony” at Vydrino, near Lake Baikal. Despite his age and failing health, he was required to do heavy physical labor.

In the bleak life of the camps, a world devoid of comfort, privacy, silence, consolation, or future, stranded in an expanse of hardened mud, dry grass, and impassible forests, beneath a horizonless sky of roiling gray clouds, Dandaron proclaimed the name of Vajrasattva. He was allowed an occasional visitor. It was said that for those who heard him directly, the effect was like a sudden clap of thunder, a bolt of lightning, a sudden opening in the sky. Some reported that those who were nearby but did not hear him directly sensed a momentary, almost painful, joy, a near but not quite accessible bright expanse hidden within clouds and beneath the plains.

Around this time, Dandaron recognized that all Vajrayana practices could be explored in the single deity of Vajrasattva. He evolved a method of practice with both a purifying aspect and a complex visualization with an outer form and an inner mandala. These, he said, were the intrinsic forms of all-pervasive radiance that extended through all of space to dissipate the ignorance and suffering of every living being.

At times, Dandaron would sit unmoving, while his breathing and his heartbeat would stop. As his followers said, he was in samadhi, a deep state of meditative concentration.

In late 1973, he fell and broke an arm and leg. He was forced to return to work before they were healed. He spoke of wanting to build a round white temple to Vajrasattva on his release. Dandaron said: “I unite all schools.”

On October 26, 1974, at the age of 59, again his heart and breathing stopped. He sat motionless for a long time but did not return to this life. The prison authorities would not say where his body had been buried. Nonetheless, the inspiration of his life and teachings remain undiminished:

Here

Radiant skies of Compassion

Shine

Without thought.Look:

Before space opensHear:

Before time beginsLeap

Into the Diamond Heart

Vajrasattva

Present

Everywhere.And hallucinations

Of the world’s pain and terror,

The world’s longing

Whirl, vanish slowly in the sky.

Just two weeks before Dandaron’s death, the painter Zheleznov, an early student of Dandaron’s and one who had been convicted in the same trial as his teacher, completed a thangka painting of the mandala of Yamantaka, Conqueror of Death. The mandala itself is a traditional presentation. In its center, Yamantaka, wrathful and with the head of a water buffalo, stands surrounded by his retinue in the pure land of his attributes and powers. Around them are the lineage of deities and teachers who have transmitted the outer and inner meaning of this great wrathful one.

But in Zheleznov’s painting, within the outer precincts of the palace are depictions of all those people most important to Dandaron: his stepfather, Dorje Badmaev; two images of his teacher, Samdan Tsydenov (one wearing humble robes, the other dressed in the ornaments of a chakravartin); and a portrait of Lama Jayagsy. Outside the mandala, among other deities and teachers, Dandaron himself is portrayed in his roles of yogi, teacher, and lineage holder. He wears prison garb, a suit, and a deity’s crown and ornaments. This, then, is how Dandaron’s disciples finally saw him and practiced as they followed him: moving through suffering and death, from life to life; invincible, indestructibly loving; and endlessly awakening.

Poems by Douglas Penick.

This article relies particularly upon the work of Lubos Beka, Vladimir Montlevich, Alexander Piatagorsky, Nicolay Tsyrempilov, and Vello Vartanou.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.