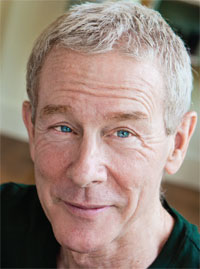

Scholar, teacher, and decades-long Tibetan Buddhist practitioner Reginald “Reggie” A. Ray, Ph.D., was among the earliest American students of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche. Ray developed a close relationship with his teacher, who, in the 1970s and 1980s, was a pioneer in establishing Tibetan Buddhism in the West.

Ray is widely respected for his knack for making Vajrayana Buddhist teachings accessible to contemporary students. He has authored four books and taught countless students, from dharma center settings to university classrooms. After spending many years as a senior teacher in the Shambhala tradition, Ray started his own community, the Dharma Ocean Sangha, in 2005.

Ray received his Ph.D. from the University of Chicago in 1973, and taught at Naropa University from 1974 to 2009. His most recent book, Touching Enlightenment, explores the process of awakening by working directly with the body.

These days, Ray devotes himself to continuing the Kagyü and Nyingma teachings of Trungpa Rinpoche. He lives in Boulder and Crestone, Colorado. Trish Deitch spoke with Ray at his home in Crestone last year.

—Monty McKeever

Can you say something about your teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche? I met him in 1970, when I was 28, a few weeks after his arrival in the U.S. He was very, very wild. “Wild” means that his main thing was not so much delivering any particular culture or tradition; to me, he didn’t even seem to be deliberately representing Buddhism. Of course, he used Buddhist language, but beyond that, there was a sense that he was blazing with sanity and wakefulness. And his main thing was, whatever strategy you had for trying to control the situation or manage him (and we all do this—when we meet each other, we always come in with ways of trying to domesticate the situation or tame it), he would simply cut through it. He had this way of exposing whatever you were trying to do. And truly, it was terrifying to be around him. But that’s my understanding of what the dharma is: cutting through all the posturing and all the armor, to lay utterly bare the reality of this moment. You’d be sitting there with him, and all of a sudden your clothes were off, you were totally naked, and your experience of life suddenly became so vivid and unbearably intense and real.

Is that literal? Your clothes were off? Well, no. You didn’t take your clothes off. But you felt that way. It felt like you were completely exposed. In that environment one changed a lot, because you were constantly being confronted with all the ways in which you might run away or hide or try to manipulate whatever it was. And particularly if you came in with spiritual pretensions— you know, this was the early seventies, and there were all of us crazy hippies (or hippie wannabe people like me). I was a scholar, but also wanting to be part of it all. But whatever it was, whatever spiritual thing you came in with, he just showed you what a fraud you were. And he didn’t have to do anything. That was the strange thing—there was just this field of awareness around him.

This field actually surrounded not only him, but Tail of the Tiger (now Karmê Chöling), the Vermont farmhouse that became one of our first communities. I remember when I would be arriving for a program: When I got to about a half a mile from the house, I would begin to feel very strange. And then I’d feel increasingly uneasy and fearful and overwhelmed with anxiety, like I was about to throw up, and I’d just want to run. But I’d force myself to go. Because we all felt the same way. We’d get there and we’d basically talk about how horrible the whole thing was, but also how much we wanted to be there because somehow with him there was so much reality and so much truth—so much life.

As far as doing mantras or visualizations or rituals or empowerments—the traditional Tibetan approach—that came later. And that wasn’t really ever the essential point with him anyway, even much later. I got from him that spirituality is about being stripped down to your fundamental person so that all the pretense and all the masks and all the defenses were gone. And he didn’t just talk about it, he did it. In fact, he didn’t talk about it, he just did it. And over time you figured out what he was up to. While it was your greatest nightmare, it was also what you most wanted.

My understanding of spirituality, Vajrayana, and Tibetan Buddhism all flowed out of those early days and the inferno of reality and transformation that you were always in when you were around him. Of course, later, a great deal of what we now understand as traditional Tibetan Buddhism was brought into his teachings, but always in service of this other, deeper thing. What I learned from him was that however esoteric or prestigious or exotic any practice might seem, it was always about the same thing: nothing more than a way to strip oneself down even further to the empty, exposed core of one’s being. Tibetan Buddhism in his teaching wasn’t about Tibet, and it wasn’t even about Buddhism—it was about being more absolutely and utterly naked as a human being. It was about surrendering more and more fully to this world, this life, this experience, and entering more deeply into it and giving oneself over to it. This astounding way of being was actually how he was as a person, and it is what he offered to me and his other early American students.

You mention that these were the “early days.” What happened later? As the seventies wore on and we got into the 1980s, his health wasn’t very good, and his energy was flagging. He was carrying so much—so many of us—and you wonder how he did it. By the 1980s, he had thousands of students, and of necessity the whole thing became more and more conventionalized. But for me he was always that incredibly awake person, unconditionally open to reality, somebody of unwavering trust in everything, with deep love for life and all its beings. He was here, he told us, to show us the path to that very same state of being. To me, it was a terrifying prospect, but also utterly attractive and irresistible.

What I learned from him is that the dharma is not about credentials. It’s not about how many practices you’ve done, or how peaceful you can make your mind. It’s not about being in a community where you feel safe or enjoying the cachet of being a “Buddhist.” It’s not even about accumulating teachings, empowerments, or “spiritual accomplishments.” It’s about how naked you’re willing to be with your own life, and how much you’re willing to let go of your masks and your armor and live as a completely exposed, undefended, and open human person. Which is what he was: he was so human.

I’d come to him as someone in an elite Ph.D. program. I came in and told him about that, and I was kind of proud of myself. He said, “You know, you can do that with me if you want to, but a much more interesting thing for you might be to come and receive what I actually have to offer. If you want to do that, I’m here.” And of course there was no question about it, and I said OK.

You say that things began to change, that he became more conventional. Well, in my experience, he didn’t. But the organization we were all creating did. I feel that almost had to happen, given our tremendous growth in such a short time. Many, many people wanted to study with him, and he obviously couldn’t relate individually in an ongoing way with all the new people arriving. He would often connect personally with someone, but then it was up to the older students to mentor them. And meantime, we were all so inexperienced ourselves. We tended to fall back on set procedures and boilerplate instructions and somewhat rigid ideas of how things should be done. To be fair, Rinpoche himself had a hand in this—he was trying to figure out a way to work with hundreds and then thousands of people. And he thought it might be worth trying the corporate model. As a Tibetan, he didn’t really have that as part of his upbringing, and he didn’t fully understand it, but he thought it was worth a try. And it did seem like this might be the answer since, as the years wore on, he had to step further back, owing to all the pressures and projects and his declining health. He was not so available to the newer students, and their experience of him was quite different and much more corporate in comparison to the experience of the first generation of his North American students.

Of course, when you know somebody on that utterly intimate level, especially someone like him, it’s going to keep going, and it did for many of us of the first generation. But it wasn’t that way with people who came along later. Especially after Naropa started, the organization became much more formal, and there were a lot of rules set in place. You know, “Here’s how you meditate.” When he taught us in the very early seventies, there were myriad different ways to meditate, and he showed us what they were. He worked with us each individually, and he would often change the instruction depending on how we needed to be working with our own mind at that moment.

But later, his teachings, and especially his Shambhala teachings, were converted into this sort of step-by-step process with a somewhat rigid curriculum. For example, over time, when you taught a Shambhala program, you were expected to follow the written word of the curriculum, and any kind of departure was frowned on. Those of us responsible for teaching were like that. In my view, we all relied too much on trying to pin everything down, mainly because, I think, our community was so large and we couldn’t think of any other way to do it. I was at Naropa, and I spent a lot of time talking with the other teachers about how we could codify and fix Rinpoche’s teachings so they would be preserved, and I think this may have been a mistake.

Why a mistake? Because, as I have learned the hard way, when spiritual instruction and mentoring become too fixed, then the vitality tends to be lost, and a person’s development is compromised. And so that occurred, beginning in the later 1970s and after. And then after that, he was ill, and the rest of us were running things. And we were doing it the only way we knew how, which was to fall back on a lot of rules to try to preserve what he had taught. But of course, his whole point was that you can’t build your spiritual life on inflexible procedures and rules and regulations, because at that point your armor is pretty much back in place. Once you start living out of “shoulds” and “oughts” and rules and credentials and levels and attainments, all of a sudden the nakedness of the journey is lost. And I think many of us did lose it.

Did he know that was happening? Yeah, he did.

Did he try to stop it? I would say yes and no. Rinpoche was interesting and, I think, quite unusual, because he accommodated a lot of things in his organization that seemed to be going counter to his own teachings. It’s almost as if he knew he couldn’t control what he had created, and in fact he didn’t want to. His basic trust in life was almost inconceivable, and it was always his thing to say, “Let’s open to this situation. Let’s explore it. Let’s see what journey comes out of it. Let’s see what happens.” He was not a person who would withdraw and try to consolidate his gains. So as a person he was always making room for everything and everyone; he himself was always open and learning at a level I can’t even imagine, and he always seemed to be changing and transforming into a vaster and vaster way of being. Watching him was like watching a star explode, rather than watching the life of a person; it seemed far more cosmic than human. Meantime, all of us in the organizations were trying so hard to protect and maintain what had been created; we weren’t keeping up with him, and sometimes it almost seemed we were going in the opposite direction without even realizing it. At a certain point, I feel, many of us just checked out from the groundless and terrifying journey he had invited us on. And, ironically, we were using his teachings to do so. I think he really knew it, and I think it bothered him a great deal.

It’s interesting to read transcripts of the Vajrayana programs he taught in the mid-1970s and compare them with the records of later programs. In the early seminars, there was so much excitement and expectation on his part, that we, his Western students, would be able to assimilate the teachings at the deepest level; that we would be this oasis of awake people in the modern world. As I said, he had been hoping that the corporate structure that we were setting up might become a vehicle for this. He trusted the teachings so much that he thought it might work.

But what I see in the Vajrayana transcripts after 1980 is that more and more, he had questions about his own organization, and he had a lot of things to say about those of us who were working in the organizations, and those of us who were the senior practitioners. And, at least as I read these transcripts, I see his early enthusiasm and hope begin to fade. He’s thinking that we’re falling short—that we’re not really taking on and living the dharma that he was teaching; that we have, in many cases, diverted his teachings into what he calls “spiritual materialism.” His own students.

You know, of course, he was human, and he wanted his teachings—which he had received from some very realized people in Tibet and which he felt were the essential core of the dharma—to be widely known. And I believe he appreciated the success. He appreciated all the centers around the world. So you get that part of it. But you also get this first thing that I mentioned, that, you know, why aren’t you people practicing more—especially the leadership? And there were some conversations about whether or not the whole setup of Shambhala—at that time called Vajradhatu—had some really fundamental problems.

I remember one time I was with him and he was very, very sad. And he would periodically go into that space where, in his own mind, he seemed to be letting it go and feeling like “No, this isn’t it.” Before his death, it became known that the Regent, his dharma heir, had AIDS, and there were increasing problems in the bureaucracy. At a certain point (I wasn’t at this meeting, but a friend who was there told me about it), he was asked, “How are we going to keep all this together?” And he basically said, “Maybe we should just let it go. Let it fall apart. It’s probably the best thing that could happen. Just let the whole thing go.” I was present at other times, at Naropa, when he said basically the same thing. At a certain point, it appeared that we’d hit a wall and things were not working. And he said, basically, if this is really the end of our effectiveness, then we have to be ready to let it go—even Naropa. There is no point in hanging on to something just for the sake of hanging on.

To me that was his personal integrity. But if we really can’t hang onto what we’ve created, what are we left with? In fact, we’re left with the living dharma itself. And the delivery systems, the official lineages, the people in the “important” positions, the Buddhist identity—they are only as good as the dharma that’s coming through them. And his message, I think, through his whole teaching career was: Create vehicles for the genuine dharma to flourish and spread, but if any particular setup isn’t delivering the genuine dharma, then it’s not worth maintaining. In fact, if you are going to be faithful to the teachings, you have to let it go. At least that’s the message I got from him personally, and it has been very impactful in my life.

Impactful in what way? Trungpa Rinpoche died in 1987. Since that time, each of Rinpoche’s senior students has had his or her own journey to try to fulfill what Rinpoche taught. In my case, after teaching within the organization for thirty-five years—17 years while he was alive and for 18 years after his death—I came to feel, whether rightly or wrongly, that it had moved so far away from the essence of what Rinpoche taught that I could no longer, in good faith, be part of it any more. At that time, I had been teacher in residence at the Shambhala Mountain Center for seven years. I lived there, having given my inheritance to the center and built a house on the land for my family. My intention, and the center’s, was that I would spend the rest of my life there practicing and teaching. My world was largely the organization and the several thousand Shambhala students I had taught over those three and a half decades. It was a terrifying and heartbreaking point to come to after all those years—to feel my only choice was to walk away.

I would not say that what the organization was doing was not legitimate on its own terms, but in my understanding, it wasn’t delivering Rinpoche’s teachings, which abide so deeply within me. I understood from Rinpoche, both from his example (he had faced a similar moment in his own life) and from what he taught, that should the time ever come when the political environment of the organization changed in certain ways—even if the safe and secure choice would be to shift alliances to some new order—we mustn’t. His message was to remain loyal to him and what we had received from him. Because—and now I see the truth of it—that was the same thing as remaining loyal to the lineage, to the teachings, and to our deepest self. When he spoke in these ways, I thought he was talking abstractly, or about the past. I never thought the day would come when it would apply to me. But of course, that day did come. He said we should stay true no matter what the cost might be. For me, the cost has been quite high, though nothing compared to what has come out of it.

Do you feel that is what you’re doing—you’re passing on what he taught you? I’m trying, but who knows? I want to transmit his lineage faithfully to others, not build monuments to myself. But of course, the possibility of self-deception is ever present. Time will tell. I will mention how close I feel to Rinpoche: Through all of the pain, dislocation, and loss of recent years, I feel held and guided by him, and often feel his still terrifying, loving, vast presence when I teach. Also, I have met and have had the chance to work with many extraordinarily open, inspired, and devoted practitioners, most of whom never met Rinpoche in the flesh, but who seem to love him and his teachings as much I do. I see these students coming alive. I see them evolving, changing, and transforming. I see them letting go of a lot of the things that get between them and their own goodness and uniqueness and creativity—their own realization, if you will. I think that’s what Trungpa Rinpoche was about. I think that’s what he was looking for.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.