The koan collection known in English as The Blue Cliff Record emerged in China almost a thousand years ago. It was born of a generous vision: awakening as part of the shared work of the world, encouraged by many voices. As with the biographies central to Chan literature, the story of the Blue Cliff is part of its legacy, its philosophy embodied in human lives and tempered by negotiations with the unexpected movements of fate.

The book was originally known as The Blue Cliff Collection (Biyanji in Chinese) and later renamed The Blue Cliff Record (Hekiganroku in Japanese). It is a poignant revision: No longer living and still taking shape, it becomes a memorial to something in the past. Sometimes you can tell how significant something is by how hard people try to manage it. That theme runs through the story of the Blue Cliff, juxtaposed with the book’s intention to open in each of us a window to the vast and unmanaged expanses of the world revealed by koans.

Buddhism comes to China from India and Central Asia and simmers for centuries with indigenous traditions, particularly Daoism. The Daoist interest in virtues like naturalness and spontaneity, the unity of the heart-mind, and practices like pure conversation (qingtan) help shape a new expression of the dharma, the koan tradition of Chan. Daoists, Buddhists, and people from different strata of society meet for private conversations, group discussions, and debates in monasteries and the imperial court. Along with ordinary speech, the conversations take place in song, silence, and even whistling, and their mood is profound and playful by turns.

In one domestic moment of pure conversation, a practitioner asks the children of his family what the snow falling outside the window is like. His niece replies, “Almost like willow down rising on the wind.” Her name is Xie Daoyun (c. 3rd–4th century CE), and she will grow up to be a renowned poet. Her response later becomes part of a koan we still use today: “When the wind blows through the pussy willows / their down floats away / When the rain beats on the pear blossoms / a butterfly takes flight.” You could see these as examples of a great doctrine like cause and effect, or you could take them into your meditation and perhaps become, for a moment and the rest of your life, willow down and butterfly, wind and rain and pear blossoms.

It will be a good while before such moments are called koans. (The Blue Cliff Collection standardizes use of the Chinese term gongan, pronounced koan in Japanese. Koan has become a loan word in English and so will be used here.) One of the earliest collections of koans is Poetic Comments on One Hundred Cases (Baize Songgu) by Chan teacher Xuedou Chongxian (980–1052 CE). He is a poet who sees the koans as literature that has the power to awaken, something he has experienced in a koanlike encounter with his own teacher. Xuedou collects a hundred stories from Chan biographies, teachings, and scriptures and writes verse commentaries on them.

Xuedou and Yuanwu evoke all the spring blossoms in hidden valleys and wild ravines where no one will see them, asking us to consider for whom they’re opening their flowers.

Xuedou’s thirty-seventh koan goes like this: “There is nothing in the three worlds. Where will you look for your mind?” (The three worlds are the realms of desire, form, and formlessness—pretty much the whole universe, material and spiritual.) This is a question the Chan teacher Panshan asked his students, and Xuedou plucks it from the record of Panshan’s teachings and responds with a poem:

Nothing in the three worlds: Where will you look for your mind?

White clouds form a canopy, a flowing spring becomes a lute:

One song and then another that no one understands.

Rain crosses the night, autumn waters deepen in the ponds.

Xuedou’s poem begins with a Chan thought: Your heart-mind is not a thing with a location, something you can find and get to work on. To use the technical terms of The Blue Cliff Collection, something more mysterious and wondrous is going on: mysterious in that the infinite and timeless universe has as its source a profound dark; and wondrous because the infinite, timeless universe is made up of particular moments, like this one of rain passing in the night over autumn ponds. Xuedou conveys this in a poetic language natural to his audience, and his commentaries help the koans move from teaching halls to literary gatherings, and from there into the wider culture.

Despite the sectarian environment of medieval Chan, Xuedou includes stories like Panshan’s from different lineages, ages, and schools, and about laypeople as well as monastics. Xuedou’s selections, drawing from a rich variety of voices, will eventually become the core of The Blue Cliff Collection.

About a century later, in the early years of the 12th century, a Chan teacher known as Yuanwu Keqin (1063–1135 CE) is working in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province on the frontier of the Song empire. The city is a crossroads for people of many ethnic groups and languages, a lively meeting place for writers, artists, and Chan people inclined toward experimentation. Yuanwu accepts an invitation to spend several long summer retreat periods teaching at Lingquan Monastery on Mount Jia, in the remote ranges of neighboring Hunan province.

Lingquan means Spirit Springs in English. The poet Li Qunyu once visited the temple, describing its halls as being filled with the fragrance of pines and the murmur of nearby waters. Yuanwu settles into a building there called Blue Cliff Cloister to give a series of teachings on Xuedou’s collection.

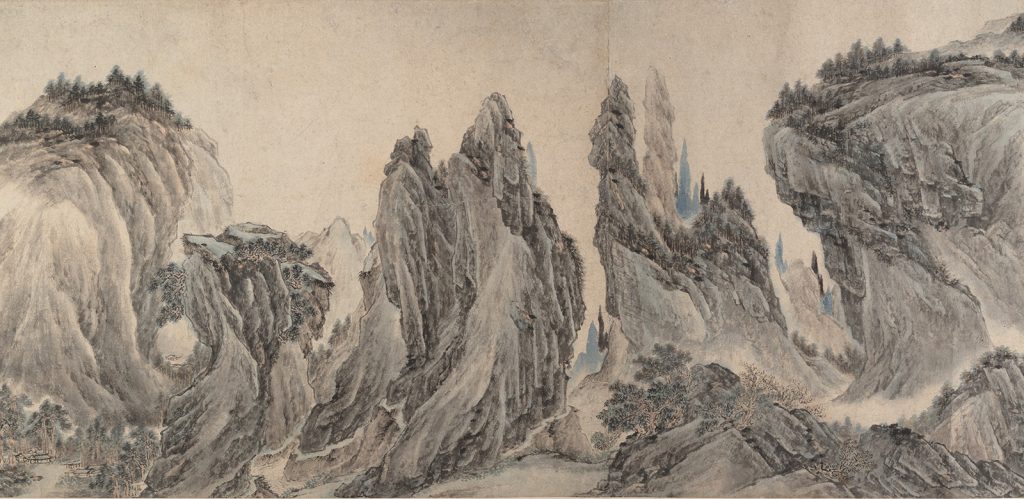

The Chinese character in Blue Cliff that is customarily translated as “blue” is really a shade of blue-green, related to some varieties of jade, kingfisher feathers, and the color of the sea under a clear sky. Mount Jia is part of the subtropical mountain ranges south of the Yangtze River, made of soluble sandstone and limestone. Over time they’ve eroded to narrow stone towers. Water pours down the mountains and courses through underground rivers. Mist seems to rise from the earth, giving the air a blue-green tint and smudging the view. Natural stone bridges hang in the sky. The haunting cries of monkeys echo from peak to peak.

It’s said that a calligraphy of the characters “blue cliff” (碧 岩) hangs in Yuanwu’s study, next to a window opening onto the mountain itself. It’s a juxtaposition like the koans: human language and the vast world, each revealing the other. Yuanwu once asks, “If a single phrase flowed from your chest, what would it be?” He answers himself, “Blue mountains, just visible on the horizon.” When someone asks Yuanwu what the calligraphy means, he quotes the founder of Spirit Springs Monastery: “Monkeys carrying their young return from beyond green peaks, birds with flowers in their beaks land below blue cliffs.” Mountains alive with monkeys, birds, and flowers—that’s what “blue cliff” means.

This landscape is quite a contrast to the windswept plains of northern China, the traditional Han Chinese homeland. In the past, northerners had tended to think of these mountains as a place of exile, the gateway to the uncertain realms of the tropical south. Perhaps Yuanwu has this in mind when he makes it such an important part of the world evoked in The Blue Cliff Collection, a lively crossroads between not just landscapes but also realms. Xuedou and Yuanwu evoke all the spring blossoms in hidden valleys and wild ravines where no one will see them, asking us to consider for whom they’re opening their flowers.

Immersion in an uncanny wilderness, the isolation of the cloister, the intensity of focus on these koans, the press of teaching at the edges of your understanding—perhaps we have a glimmer of what that might be like for Yuanwu. And then at summer’s end he comes down the mountain and back to the city, into bustle and conversation. With the help of colleagues and friends, he spends a decade or two interweaving Xuedou’s koans and poems with his own commentaries, which originated with his talks at the Blue Cliff Cloister. You can hear the different viewpoints—philosophical, lyrical, polemical, insistent, wondering—braided into the text.

Yuanwu’s individual voice has a bracing directness, and he asks good questions. His introduction to one koan says, “When ‘like this’ will work and ‘not like this’ will work, too, that comes from being too timidly disengaged. When ‘like this’ won’t work and ‘not like this’ won’t work either, that comes from being dangerously aloof. To avoid getting mired in either of these paths, what will you do?” When Xuedou refers to the legend of the carp who leaps up a waterfall to become a dragon, Yuanwu asks the essential question: “Yes, but where is that dragon now?” He’d be pleased if you showed it to him. Yuanwu sets the template for future koan collections by generously quoting other people—as with the Chan teacher Fayan’s unforgettable image of ripe fruit heavy with monkeys—and providing backstories for the characters, events, and ideas that appear in the koans.

Near the end of Yuanwu’s life, the manuscript of The Blue Cliff Collection goes back to Mount Jia, where it’s edited—how much we don’t know—and turned into a printed book. The contributors to the Collection—Xuedou, Yuanwu, and the people of Chengdu and Mount Jia whose names we don’t know—settle the house of the koans on the ground and open its doors and windows. Almost as quickly as they do, the Collection vanishes when Yuanwu entrusts it to his dharma heir Dahui Zonggao. He’s made an interesting choice: Dahui so strongly disagrees with Yuanwu about koan study that he apparently destroys every copy of the book he can find and burns the wooden blocks to keep more from being printed. It’s as though the book were a stream on Mount Jia, bubbling from a spring for a while and then disappearing underground.

Dahui is a teacher single-minded about helping people wake up. He listens to his students, including women, and when they have difficulty, he doesn’t assume that they’re the problem but improvises with koan practice until something works better, and those innovations live on today. Dahui thinks Xuedou’s and Yuanwu’s literary approach is a distraction from the simple imperative of waking up, and he wants to put a stop to it.

Every difficult conversation and moment of grace, all the subway rides and trail hikes, your dreams and what happens in the many rooms of your meditation—it’s all the koan.

Fortunately, Dahui doesn’t succeed, though The Blue Cliff Collection’s survival is touch and go for almost 200 years. Around the time of Dahui’s purge, the Collection is also banned by the government for its portrayal of emperors—not, you won’t be surprised to hear, actually a major theme of the work. The book circulates underground, handwritten copies passing from hand to hand. The koans would probably consider this time in the dark as vital as any other in their history.

In about 1300, The Blue Cliff Collection reemerges into the full light of day when a handful of these samizdat copies are collated and published in a new edition, with some pieces missing—an introduction here, a comment there. Fate and the Dao have contributed their edits. The book stays aboveground from then on, eventually crossing oceans, continents, and language barriers around the world.

Over that time, Yuanwu’s vision will inspire poetry, painting, calligraphy, theater, architecture, and even landscape design. He shows how the koans belong in the world, how our souls are part of the koan tradition. For centuries of students, Dahui has pointed out the particular words in a koan that open to the vastness. Dahui insists that our enlightenment, whoever we are, is the part of the tradition that matters. Yuanwu publishes a book to make the study of koans widely available; Dahui works intensively with the students who find him. In a quintessentially koan move, the tradition will come to see their two viewpoints as complementing each other, forming a richer whole.

The Blue Cliff Collection travels to Korea and Japan. According to one story, Dogen copies the book by hand on his last night in China, bringing the One Night Blue Cliff (Ichiya Hekigan) back to Japan with him. The scholar Steven Heine was given an explanation at Mount Jia that he thinks is more likely: A copy of the book is sent to Japan for safekeeping after its banning in China. Whatever the case, The Blue Cliff Collection has landed in an auspicious moment, and flourishes in Japan. Two revitalizers of Japanese Zen in the 18th century, Hakuin Ekaku and Tenkei Denson, write about the Blue Cliff koans in a way that forms a bridge from Xuedou’s and Yuanwu’s sensibilities to our own, suggesting that, despite the name change to record from collection, the book is still taking shape.

The focus of koan study as it developed in Japan and came to the West has often been on a practice that is solitary, even secret. You’re hoping to match your realization to the ancients, with your teacher as adjudicator, through a process you rarely share with anyone else. As a teacher, I was interested in the original Blue Cliff vision of awakening as a shared project, what my community would call a conspiracy of friends. It occurs to me now that thinking of a koan record might lend itself to creating a koan curriculum, a study of that record, while imagining a koan collection might lead you to create opportunities for the gathering to continue.

Our koan practice includes private meetings with a teacher and intense individual work in retreats, and it also involves taking up koans in a group. For example, we met every week for years in a koan salon, made up, like that circle in Chengdu, of koan students, artists, and activists, except that we were thoroughly 21st-century folks in the high desert of New Mexico. I would bring in a koan and provide an orientation. We would tuck the koans into the pockets of our lives and notice what happened over the following week.

Inviting a koan to accompany you in this way means accepting that everything that happens while you do so is the koan: Every difficult conversation and moment of grace, all the subway rides and trail hikes, your dreams and what happens in the many rooms of your meditation—it’s all the koan. And the koan is the world calling you home. You walk out to meet that call by making yourself fetchable, becoming a person of greater warmth and curiosity, of more courage and fewer opinions, of an attentive stillness. At the next salon we placed our experiences, questions, and commentaries next to each other. We gave responses rather than answers, creating a koan field of juxtaposition rather than contest.

Eventually I wondered what would happen if we switched from koans chosen for this particular assembly to an unmediated encounter with the ancestors of The Blue Cliff Record. In the first koan, about Bodhidharma’s meeting with the emperor when he first arrived in China, the emperor expresses his regret over how their encounter has gone. We spent a gray and golden afternoon considering this regret, and eventually a moment fell open in which the poignant transience of the things we care about became, right there in the room, the ceaseless rising and falling of impermanence; personal regret opened into an experience of the vastness as it is.

This really is a conversation across time and space, generations and continents. Experiencing such moments told me all I needed to know about the power of the Blue Cliff vision of awakening as the shared work of the world.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.