I.

Renunciation comes by degrees, has many aspects, and goes by many names. Letting go, abandonment, non-grasping, relinquishment, and dispassion are all, at root, forms or aspects of it. Morality, generosity, compassion, and mindfulness are all expressions of it.

But renunciation is not just an interior matter. It requires that one give up real things, actual sources of pleasure, comfort, or security. Only by restraining our preferences in regard to such things can we learn what they really give us. Only through such restraint can we discern, among the many things we pursue, what it is that nurtures the peace and clarity we seek, and what it is that drives us on to further seeking. Through renunciation we discover that our existence is bound up with our preferences but is not limited to them.

Many of us understand, if imperfectly, the wisdom of refraining from self-harm, controlling our impulsivity, or delaying gratification. But we understand such forms of self-restraint as preferences. We want to exercise restraint in these ways when we feel it would be for the best. Renunciation goes further, questioning the logic of preference itself, the desirability of desire. Yet as I’ve come to understand it, the aim of renunciation is not to do away with desire in some absolute sense, but to turn away from it, toward a fulfillment apart from its ends.

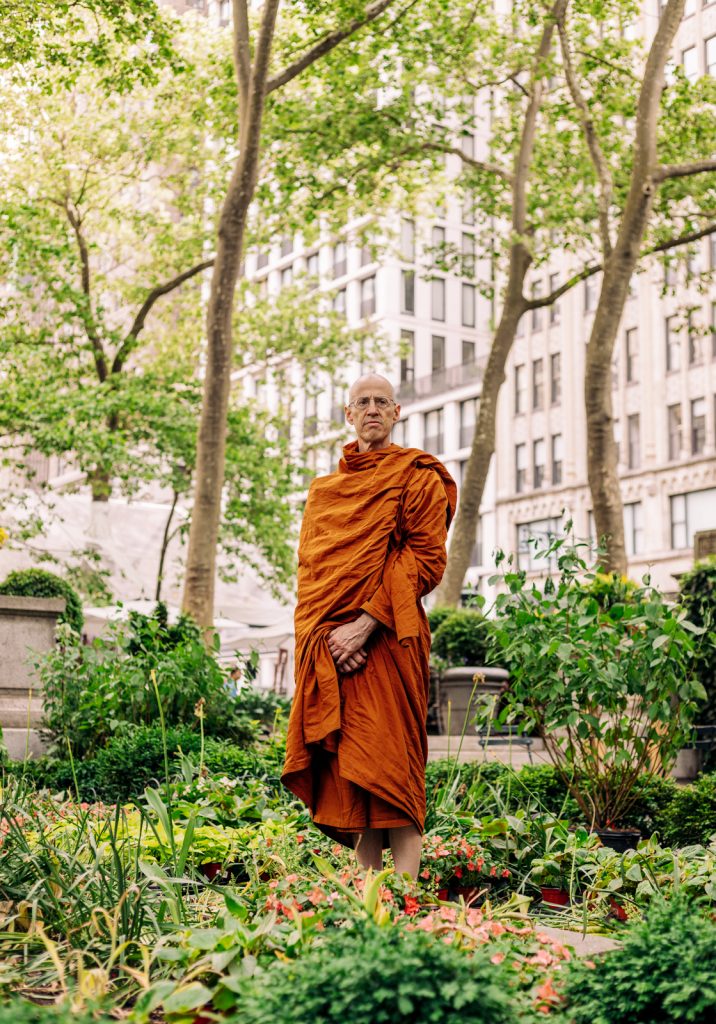

To cultivate a renunciatory spirit in secular life entails both self-restraint and self-awareness with regard to one’s preferences. It requires this amidst the ever-surging flood of desires and aversions, opportunities and threats in which “the world” immerses us. Monastic life simplifies this dance of renunciation. Indeed, it obviates the need to think about it, at least at first. The received view in the Western branch of the Wat Pah Pong order, in which I ordained, is that a monk has only to “surrender to the form”—the fabric of customs, rituals, strictures, duties, observances, and deferences of which life in a WPP monastery is woven—and a balance of appropriate, mindful restraint will strike itself. “The form” allows only what is helpful, and offers unlimited occasion for mindfulness. It provides the ideal “container” for a life devoted to meditative practice, the chief occupation of every forest monk, at least notionally. By shaving the head, wearing robes, withdrawing from sexual life, forswearing the use of money, and eating only in the morning—along with many, many other strictures—the monk binds up her energies and situates herself in restraint. Her expectations narrow, her level of stimulation attenuates, and her inner weather calms—ideal conditions for meditation to deepen. (I use the feminine here to include the many female monks who have now been ordained in Theravada Buddhism, if not in the WPP order.) The monk thus adopts external renunciatory practices in part to effect an internal shift. The external practices are means to an end.

II.

I undertook one such practice on my own years before moving to the monastery. I didn’t think of it as a renunciatory practice, and at the monastery it was regarded as an add-on—not an entailment of “the form” but a personal austerity that a monk might pursue in addition to it. But the practice did have its own catchphrase in the WPP Order: “putting away the books.” This practice descends from Ajahn Chah himself, founder of the broader Thai WPP group of monasteries, and the monastic teacher I most admire. Here is how Ven. Chah assigned this practice to one group of monks:

Take all the books and lock them away. Just read your own mind. You have all been burying yourselves in books from the time you entered school. I think that now you have this opportunity and have the time, take the books, put them in a cupboard and lock the door. Just read your mind.

For me, “putting away the books” may have seemed like a stretch, more self-mortification than renunciatory Middle Way. Books had been at the center of my life from childhood. I’d read for pleasure, consolation, escape, and sometimes knowledge almost every day since learning to read. I’d pursued a career as a writer, editor, and teacher for decades. I believed in books. I also believed, if a bit fuzzily, in small “l” liberal values—reason, science, critical inquiry and debate, democracy, human rights and equality, the value of the individual—that depend on literacy and numeracy. On books.

Yet I’d been willing to “put away the books” right from the start of my journey on the path of Buddhist dharma, years before coming to the monastery. I did so to attend a bookless—and silent—ten-day meditation retreat. On that retreat, I’d discovered an entire world lying just beneath the layer of language and stories habitually occupying my mind. After just three or four days spent mostly in meditation, but the first such days of my life, I experienced a kind of brightening of mind. Sensations and perceptions—sounds, images, feelings, and their accompanying narrative streams—all emerged in a heightened awareness that seemed at once new and familiar. The contours of the mind’s foreground grew clearer, and so too did its uniform background, a silent, still, dimensionless vastness. My briefly sustained devotion to “just read[ing] [my] mind” thus opened a door to the field in which all experience unfolds.

I wanted to go through that door, whatever I had to renounce. From that retreat forward I’d narrowed my reading to books about the dharma, and I scaled back significantly on writing. I maintained these practices after coming to the monastery, barely reading at all during the four silent, three-month winter retreats that I undertook there. I knew I was subduing something vital in myself—my reading, writing, thinking mind. But subduing this seemed necessary to access that underlying subterrain of quiet stillness. In this sense, choosing to renounce “the books” suited my personal aims and interests, and countered my particular rationalistic tendencies.

III.

Yet “putting away the books” also dovetailed with “not being somebody special,” another of our many catchphrases at the monastery. This maxim has several meanings that blur together but only partially overlap. First, “don’t be somebody special” means, don’t be egotistical, in the everyday sense of conceited, vain, or self-centered. Dressing in shapeless brown garments, eating on a schedule incompatible with comfort, giving up intimate relationships, and relinquishing the personal agency afforded by money—such practices wear away at one’s habitual self-regard. “Putting away the books” served a similar function, undermining my sense of the importance of my own stories and ideas.

But in the language of the WPP Order, “not being somebody special” also refers more broadly to bhava (“becoming” or “identifying”). In this sense, it means refraining from understanding or defining oneself, and thereby creating oneself, in terms of what one does, thinks, feels, or more broadly, is at a given time. This notion underlies the common advice in dharma circles not to believe, not to inhabit, such perceptions as “I am certain of X or doubtful of Y,” or “I am angry or calm,” or “I am a success or failure…”—say, as a writer, or for that matter, as a monk. To believe such perceptions is to reify a passing condition as an essential self. “Not being somebody special” thus connotes an ultimate, absolute kind of renunciation, the letting go of any enduring sense of self at all.

For me, “putting away the books” may have seemed like a stretch, more self-mortification than renunciatory middle way. Books had been at the center of my life from childhood.

These two meanings—not being egotistical, and not identifying—blend together in the following reflection by Ajahn Sumedho, the American founder of the Western WPP monasteries:

I remember that in my own experience, I always had the view that I was somebody special in some way. I used to think, ‘Well I must be a special person.’ Way back when I was a child I was fascinated by Asia, and as soon as I could I studied Chinese at university, so surely I must have been a reincarnation of somebody who was connected to the Orient. But… no matter how many signs of being special… you can remember, …they’re anicca [‘transient’], dukkha [‘unsatisfactory’], anattā [‘not self’]. [In our practice,] we’re reflecting on them as they really are. What arises ceases. Whatever it is, it can be used for mindfulness and reflection—that’s what I’m pointing to, how to use these things without making them into something. This I trust: …in just waiting, being nobody and not becoming anything, but being able just to wait and respond.

Notice that the egotistical thought that Ven. Sumedho cites, “I must be a special person,” does not exhaust his category “whatever it is.” Any phenomenon whatsoever, not only egotistical thoughts but anything at all of which one can be aware, “can be used for mindfulness and reflection.” For Ven. Sumedho, “being nobody” goes beyond being less self-dramatizing or more humble. It asserts our potential, through practice, for dwelling in a peaceful awareness of “not becoming anything.”

Learning not to “become” egotistical made sense to me, but I was less certain about the mysterious condition of “being nobody.” Not “becoming” any of one’s potential motivations or inclinations—whether egotistical or, say, altruistic—sounded to me like self-abnegation and quietism, notwithstanding Ven. Sumedho’s mention of somehow “being able to respond.” It sounded like denying my own initiative and discernment in favor of a passive faith in some extrinsic, mystical agency.

Nonetheless, Ven. Sumedho’s teaching conveys—lyrically, if elliptically—the renunciatory aspect of mindfulness practice. The blend of the two meanings I’ve discussed of “not being someone special” helps us to understand mindfulness as a respite from both the endless labor of keeping one’s ego inflated, and the rollercoaster of self-construal on which we swoop and curve through the good and bad of worldly life. I recognized the yearning for this respite as lying close to the heart of the renunciatory impulse that had brought me to the monastery.

IV.

But there is a third meaning of “not being someone special” that I found less compelling. Sometimes the monks used the phrase to refer neither to being humble nor to being no one, but rather to being like everyone else. In this sense, the phrase promotes an exclusive group identity centered on sameness. The phrase cautions against, or rebukes, expressions of personal identity that deviate from the norms of the monastery. And implicitly, the first two meanings of “not being someone special”—not being egotistical, and not identifying—link a monk’s failure to conform to egotism and spiritual cluelessness.

With this third meaning in view, the practices constituting “the form” emerge as markers of a normative identity, that of the “good monk.” Apart from effecting any internal shift, “the form” defines a cultural code, and functions—in the manner of a “total institution” like the military or a mental asylum—as an instrument of social conditioning. To be a “good monk,” one “surrenders to the form” in this cultural, observable sense. The “good monk” is evidenced not by spiritual insight but by comportment. He is meek, laconic, and compliant. Foremost, he is loyal to the monastic hierarchy, and especially to the senior monks who interpret and codify “the form” for the rest.

Thus, while all manner of shortfalls are forgiven, any monk who is to remain at the monastery must learn—and the “good monk” must master—submission, if in the name of “surrender.” Every new monk enters monastic life “in dependence” on an acariya, a particular senior monk in the role of teacher and benefactor. In the Western WPP monasteries, juniors relate to seniors as disciples to gurus, often serving literally as their personal servants. The exemplary junior monk defers to his acariya not only in matters of conduct and observance, but also in his personal decisions, views, and all spiritual matters.

Questions and doubts are allowed, but only to the degree that the “dependent” monk couches them in deference and hesitancy. If questions and doubts harden into dissenting views, the monk holding them must keep quiet about them, or better, strive to abandon them. Indeed, there is a prescription for the monk who “doesn’t get it”: the monk should direct his mindful awareness to his doubts and “wrong view,” know these as doubts and views, and abide in the peace of the knowing mind until whatever doubts and views have arisen within it, like all other conditioned phenomena, pass away. By persevering in this practice, he will arrive at confidence in the rightness of the views endorsed by the senior monks. These are right because the senior monks are the final arbiters of tradition, and as a first principle, tradition is right. By renouncing his individuality, his personal agency, and his independence of action and mind, the monk thus embraces “the good way.”

Yet despite the authoritarian flavor of the WPP training system, amazingly, the “dependence” that I’d accepted delivered just what it promised, and indeed what I’d come for: uniquely supportive conditions for long-term, committed meditative development. I’d set aside deeply-held values, attitudes, and activities on which I’d staked my identity. I’d put myself in a position where my personal inclinations were frustrated at every turn. I’d given over responsibility for my decisions to paternalistic, dogmatic authority figures. In exchange I’d received a set of understandings and practices to test against my experience, and—beyond our half days of menial duties—abundant free time for meditation.

V.

Bracketing off my reservations about our little society, I spent countless hours, the majority of this free time, in solitude, meditating in my cabin and walking in the fields and forests of the monastery. Metaphorically, the ground did shift for me during this time. Insights unfolded in what felt like a self-steering, self-sustaining process. This was anything but a smooth process, as my reflections here may suggest. There were long periods of water-treading, spikes of frustration, fear, anger, resentment, boredom, and tailings off into despair. But despite the many things that had come to seem wrong with my life at the monastery, there was an underlying sense of correctness, of being on the right course. And there were experiences of sublime beauty and meaning, “openings” of heart and mind, expanses of joy, clarity, and calm.

We were encouraged not to evaluate or interpret our meditative experience, not to fret over our progress, not to grasp for “attainments.” To avoid fixing our private experiences within a rigid framework of concepts, my acariya advised me not to talk about what I experienced too much—yet another restraint. The idea was to let intuitive awareness guide us towards understanding. Wisdom would deepen of its own accord. One undertook such self-silencing, as one did “putting away the books,” not only for the inner stillness it might enable, but to turn from theories of experience to experience itself. It was “concepts”—thinking and deliberation—that were to be renounced. From this would follow gnosis: “seeing things as they are.” Of course, this too is a theory, one drawn from the full set of maps and frameworks endorsed by my seniors at the monastery.

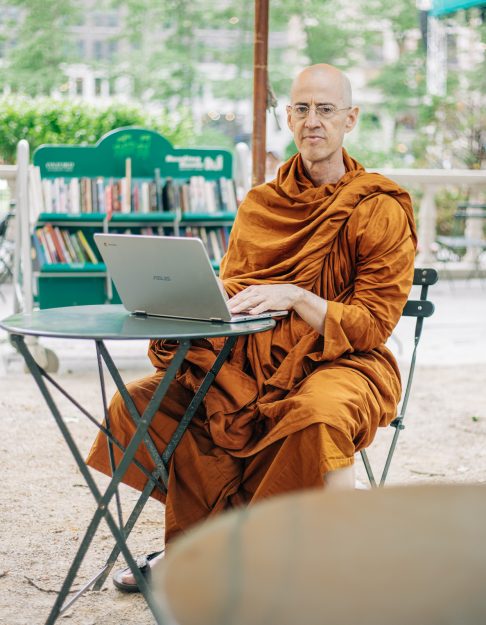

There were also, well, books. As I’ve suggested, “putting away the books” was never an absolute for me. I approached complete abstinence during the winter retreats, but for the other nine months of the year, I continued to read in a measured way. I simply couldn’t accept, as our orthodoxy implied, that ignorance (avijjā) had one meaning in the Buddha’s teachings—an exclusively spiritual blindness—and another in our modern age, in which ignorance and book-banning are synonymous.

At first my reading focused on the most approved genres—the only ones in which junior monks were encouraged to read. These were books by Thai forest masters like Ajahn Chah, along with books by their Western disciples, the teachers of my teachers at the monastery. I also read steadily in Buddhist scriptures, a somewhat less-approved genre due to its potential for mishandling by juniors who “didn’t get it.” For perspective, I began reading as well in other Buddhist traditions and in academic Buddhist scholarship. In my fourth year at the monastery, my growing knowledge of the early Buddhist dharma—in particular, what I discovered to be its foundational commitments to reason, open-mindedness, and critical inquiry—led me onward (or backward) to less explicitly Buddho-centric readings in philosophy, physics, and neuroscience, the dharma of nature.

Where the carefully circumscribed guidance of my immediate teachers left me confused about my meditative experiences, my wider reading—in view of both the unities and the inconsistencies I found—led to insight, and in the best sense, disillusionment. My experiences in meditation, though reflected in many of the frameworks I encountered, did not fully conform to any of them. I couldn’t take any lens—traditional, Buddhist, modern, or otherwise—as transparent, as a means to somehow “direct” experience, to “seeing things as they are.”

Rather, I came to understand that perception constructs, rather than relays, our experience. Experience is unavoidably theory-laden, whether the theory involves a progression of clearly-delineated jhana “attainments,” supernormal powers and realms, or natural psychophysical processes. But perhaps the discrepancies between the paradigms of the early Buddhist scriptural teachings, the Thai forest tradition, other traditions, and modern naturalism saved me from shoehorning my experience into any one particular framework. I came to renounce the illusion of “seeing things as they are” in some ultimate sense, along with any source of authority with claims of transcending interpretive frameworks.

As “putting down the books” had been necessary for my meditative development, picking them back up thus proved crucial to understanding it. Ajahn Chah himself explains, “when you have examined and understood the mind…, then you have the wisdom to know the limitations of concentration, or of books. If you have practiced and understand not-clinging, you can then return to the books. They will be like a sweet dessert.” It isn’t that “the books”—or by extension, thinking and explicit learning—are categorically bad in Ajahn Chah’s view. Rather, both “the books” and the meditative “concentration” afforded by putting them down entail “limitations.” Each is subject to “clinging”—whether to intellectual knowledge in the case of “the books,” or to the refined pleasures of deep practice in the case of “concentration.” Ajahn Chah directed his orders to “put away the books” and “just read your mind” at young monks from education-oriented backgrounds. We should therefore understand these directives as situational, rather than as laying down a blanket principle of renunciation. Once “putting down the books” has served its purpose, Ajahn Chah suggests, letting go of this practice—renouncing “putting down the books”—may be valuable, even “sweet.”

Might such situational reasoning apply as well to other practices, aspects of “the form” I’d approached as renunciatory practices, but that I’d come to find sexist, fatalistic, authoritarian, or obsessive, and thus anti-spiritual? No. One wasn’t to pick and choose where “the form” was concerned. My teachers presented the WPP version of monastic life as a unitary, indivisible whole synonymous with the vinaya, the monastic discipline set forth in the Buddhist scriptures. But while “the form” does indeed center on truly ancient, vinaya-rooted renunciations—the robes, the alms bowl, the celibacy, the putting down of money, the ethical restraints—my reading revealed countless regulations and customs accreted over time from other sources. These sources include cherry-picked commentarial interpretations; Thai gender, family, and other cultural sensibilities; the royalist, nationalist agenda of Thai ecclesiastical authorities; and the conservative social and religious biases of the Western “elders” of the Order.

I learned moreover that even our bedrock monastic reality of living in a monastery—much less one of the handful of insular, exclusive Western WPP monasteries—is not the only form of renunciant life available to a Buddhist monk. I read in the Buddhist scriptures of forest-dwelling monks, town-dwelling monks, park-dwelling monks, wandering monks, and monastery monks. In secular Buddhist scholarship, I read that even this pluralism likely represents a retrospective narrative compression of succeeding historical phases into an idealized original period. Throughout Buddhist history, I learned, the establishment of monks in monastic institutions has been intermittent and uneven. For instance, the confinement of Thai forest monks to monasteries—after centuries of wandering in actual forests—developed as a consequence of the deforestation and political consolidation of modern Thailand.

Ajahn Chah’s conditional endorsement of “the books” aside, the main implications of such conclusions bore not on monasticism, but on me. From the viewpoint of the “good monk,” I had “lost my way.” I’d failed at “putting away the books.” I’d let myself think and question. I’d lost the sense even that thinking and questioning were inclinations of mind to renounce. I seemed to have come full circle, back to the small-“l” liberal values mentioned above which begin with and follow from reason and critical inquiry. I could not reconcile these values with “the form” as I’d come to understand it. Thus, I was failing too at “surrendering to the form” in its authoritarian aspects, and at “being nobody” in its conformist sense.

The exclusive ethos of the WPP order leads most who join it to conclude that a monk unwilling to accept “the good way” has no way to move forward as a monk, and hence no other option but to disrobe and leave. After five years at the monastery, I was indeed no longer willing to accept “the good way” as a good way. And so I left.

VI.

I didn’t disrobe, though. I’d internalized enough of the ethos of the order that part of me felt I should. Indeed, an inner drumbeat of shame had pushed me towards disrobing for over a year. But “the books”—and my growing disillusionment with the order—empowered me to decouple disrobing from leaving the monastery. I wasn’t a perfect monk, but by any reading of the vinaya, I remained a monk in good standing. Indeed, the monastic code allows a monk who loses confidence in her acariya—one might argue, requires such a monk—to renounce “dependence” on that teacher, and to leave that teacher. This ancient allowance reflects the characteristic wisdom of the canonical Buddha: in the end one must trust one’s own deepest discernment as the only way (if not a foolproof way) to find one’s way forward.

At bottom, I like being a monk. For me, the Theravada monk’s defining restraints bring a baseline sense of calm, of simplicity, of living a harmless life that I value. I prefer this way of being to the more burdened, impassioned, distracted life I led in “the world.” And I’d learned that leaving the monastery did not necessarily mean returning to “the world.” “The world” is not a place. It’s an inner churn. In this sense, renouncing “the world” turns out to be a matter of preference after all, a preference for peace and clarity over churn.

Monasticism can offer support for this preference to the extent that it supports renunciation, but only to this extent. Many convert Buddhists will surely continue to find scope for spiritual development—and a few will find monastic homes (if not homelessness)—in convert-led “traditional” monasteries like those of the Western WPP order. Many will make shorter stays, and some will benefit from them, as I did. I don’t know where else but a monastery one might hope to find support for the years of secluded practice that I found in New Hampshire, a mode of training with a qualitatively unique transformative potential.

Yet at some point in the drive to uphold and perpetuate “the form,” the Western-convert monastery tips its monks from renunciation into identifying and inflating themselves with its various practices. This is sīlabbataparāmāsa, “clinging to rules and rituals,” a spiritual danger against which the canonical Buddha warns his monks repeatedly. We can cling to anything, from the customs of another culture to those of our own, from books to renouncing books, from “the world” to the world of a given monastic order. We can mistake renunciatory means for religious ends. The same external forms that for a time support inner development may come, as conditions change, to impede or reverse it.

The challenge is to discern which externalities—traditional or otherwise—lead one forward, and which hinder our development. We can fall short in our renunciatory practice, failing to challenge our preferences, failing to risk discomfort of body or mind, failing to question the reality of the self we fashion out of our pleasures and statuses. Or we can go too far, beyond Dom Cuthbert Butler’s “natural asceticism” of renunciation, into obsession and compulsion, self-punishment and bodily “purification,” and subjugation to hierarchies and belief systems. The arch-conservative, non-negotiable cultural forms enforced by the Western-convert monastery finally lead many, as they did me, into a spiritual cul-de-sac.

Since leaving the monastery, I’ve turned to the project of renewing my life as a monk. I’ve lived with other independent monks, studied and practiced alongside diverse lay Buddhists, and spent time at an urban temple where the monks, all native Thais, practice in the Thai forest tradition (of a parallel order) in ways refreshingly different from their Western-convert counterparts in the WPP order. These experiences have strengthened my sense of the possibility I found in “the books” of a range of viable lifeways for monks beyond the monastery.

A Theravada monk must live by the vinaya—it’s what makes her a monk—but this does not preclude a life aligned with her values. And not everyone with renunciatory aspirations needs to be a monk; there are many whose values, in view of their commitments, preclude a life in robes. For me, the illiberal values that the Western WPP “elders” preserve by or impose on tradition—some to the extent of discounting books—proved unworkable. I’ll long remember my heart sinking at the noncommittal smiles of the senior monks, and the uncertain chuckles of the juniors, when a monk shared news one morning of a recent book-burning at a forest monastery in Thailand.

We may need new institutions—perhaps with more fluid boundaries and flexible exits—to offer shelter from “the world” for dedicated renunciant practice uncompromised by ideology. We may need to reinvent traditional gift economies such that monks in the modern world can find reliable support informally, person-to-person, as they wander. We surely need a broader range of possibilities for all who wish to develop as renunciants, in or out of the robes, not only through meditation, but also by thinking and questioning, reading and writing. We need this precisely for the purpose of narrowing and then living our understanding of what renunciation entails: not subjugation to a fixed set of customs, beliefs, or restraints, but a turning towards inner freedom.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.