One Mind

Directed by Edward A. Burger

Commonfolk Films, 2016

China, 81 minutes

In the spring of 1986, as soon as foreigners could acquire permission to travel into the remote mountains of south central China, I set out on a journey to locate and contemplate the monastery ruins once inhabited by the most famous masters of Chan Buddhism’s golden age. Although it was well known that what remained of these slowly deteriorating monasteries had been brutally destroyed in the Cultural Revolution, I had hoped to see what little might still be visible. In the midst of these explorations, I wandered into Zhenru Chan temple in Jiangxi province, which was not only intact but also inhabited by a handful of Chan monks who had been allowed to continue their traditional practices in rural seclusion despite government suppression everywhere else. What I saw there was extraordinary, a profound trace of a lost world. Although images of this monastery remain vivid in my mind, I hadn’t been back again to visit in the intervening 30-some years. So it came as a very pleasant surprise when I was asked to review the superb film One Mind, a documentary contemplation of the meditative life at Zhenru temple.

It would be entirely inadequate to say that One Mind, directed by Edward A. Burger, is about Zhenru (“True Suchness”) Monastery, although it certainly is. The film is more importantly an open exploration into the state of mind that is cultivated and lived at Zhenru Monastery, experienced through the filmmaker’s own longtime participation in this meditative way of life. One Mind (yixin) was the phrase used by early Hongzhou Chan masters to name this quality of profound awareness, and it has been carried through the monastery all these centuries into this revealing film, communicated through masterful technique and the filmmaker’s own personal experience.

The film opens, sans visuals, with the brisk sound of wind in bamboo, and it’s soon understood that the film’s soundtrack is fundamental in evoking this Chan state of mind. Later on, we hear the sounds of what we are seeing—monks’ sandals scurrying into the meditation hall, then their breath; heads being shaved; rain on stone; wooden fish clapping. When a storm bears down on the monastery, a monk pounds a huge drum, matching the power and fury of the thunder—a breathtaking minute of sound and sight. At other times, on carefully chosen occasions, silence prevails.

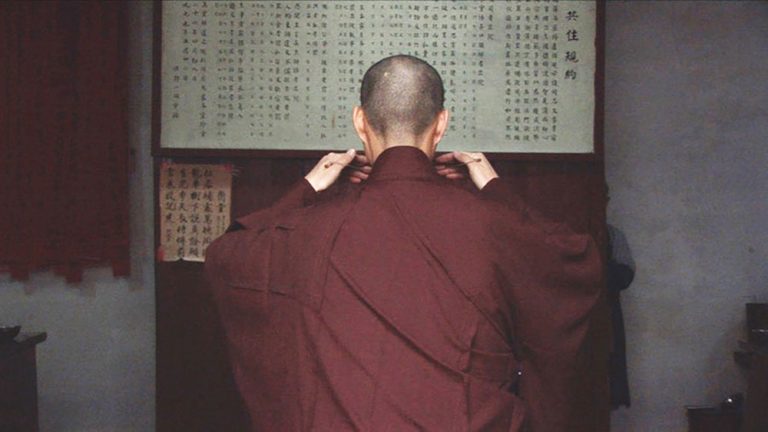

Moving along in perfect alignment with the sounds of the monastery are exquisite visuals. Close-up shots alternate with wide-open perspectives. Sometimes we see only a fragment—monks’ walking feet but not the monks; a single worm struggling in the topsoil as a monk hoes the ground. And sometimes the entire valley comes into view, contextualizing the community in overall space. Although the film is shot in full color, the monastery and valley come in earthly, muted hues. Everything seen is wood, stone, metal, and ceramic, with dim light and fog muting these already matte organic colors. Browns, greens, and grays are the color of bark, leaves, and well-worn monastic robes rather than of glossy painted and plastic surfaces. As is true for Mennonites and other religious communities committed to an older order of existence, these basic elements of wood, stone, and earth constitute the world.

And just as it is in Zhenru Monastery, language is at a premium throughout the film. The filmmaker doesn’t narrate; there are no wordy descriptions telling us what the monks are doing. They just do it, and viewers are there to witness. This is not to say that language is entirely absent, however. It does appear in three fitting ways. First, the film begins with passages on the screen inspired by the final chapter of the Avatamsaka (“Flower Ornament”) Sutra, in which a pilgrim, Sudhana, travels arduously in his quest for enlightenment through many landscapes and teachers to consult the bodhisattva Maitreya. “Great Teacher,” Sudhana pleads, “please guide me on my quest for an awakened mind.” “Young Pilgrim,” Maitreya replies, “to find the awakening you seek, turn your gaze inward now toward the landscapes of the mind.” As the film progresses through various monastic practices of labor and meditation, further instruction from Maitreya is projected as text upon the scene. These occasional teachings help set the Chan practices we are observing into the larger Buddhist context of the quest for enlightenment.

The film’s second use of language is when a monk addresses the viewer about what he is doing. This language is subtle and multilayered. It tells us about tea or turtles or gardening or head shaving, but in each case there is at least one more layer of Chan wisdom explicitly spoken or implied. Picking tea is about tea, but it is also about mindfulness and awakening. And the third form of language in the film is the monks’ ordinary worldly talk: “Put it here” or “It’s time to finish our harvest.” In many of these moments there are no translated subtitles. If you understand Chinese you can hear what they’re saying, but for the most part you’re better off not understanding, so that these sounds and their human origins blend into the background audio just like the babble of the stream. Other than these three occurrences of language, the film offers no story line; no individual human interest stories. “True Suchness” tells its own story.

Because we see monks engaged in the chores of the monastery through all four seasons, we know that One Mind was not the work of a large film crew flown in for a frantic three-day shoot on location. Indeed, the long-cultivated meditative quality of this film has already been conveyed to us throughout, clearly the effect of the filmmaker’s having been a resident in the monastery and a participant in its communal life. He is thus able to show us not only the detail of Chan monastic life but also how it coheres in the experience of “one mind.” The result is a deeply moving glimpse into classical but contemporary Chan meditative life. At one point Maitreya instructs Sudhana: “Young Pilgrim, continue forth in gratitude,” and gratitude is precisely the response that One Mind is likely to evoke from its audience. This is an authentic Chan film.

One Mind was screened on Tricycle’s Film Club in December 2017.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.