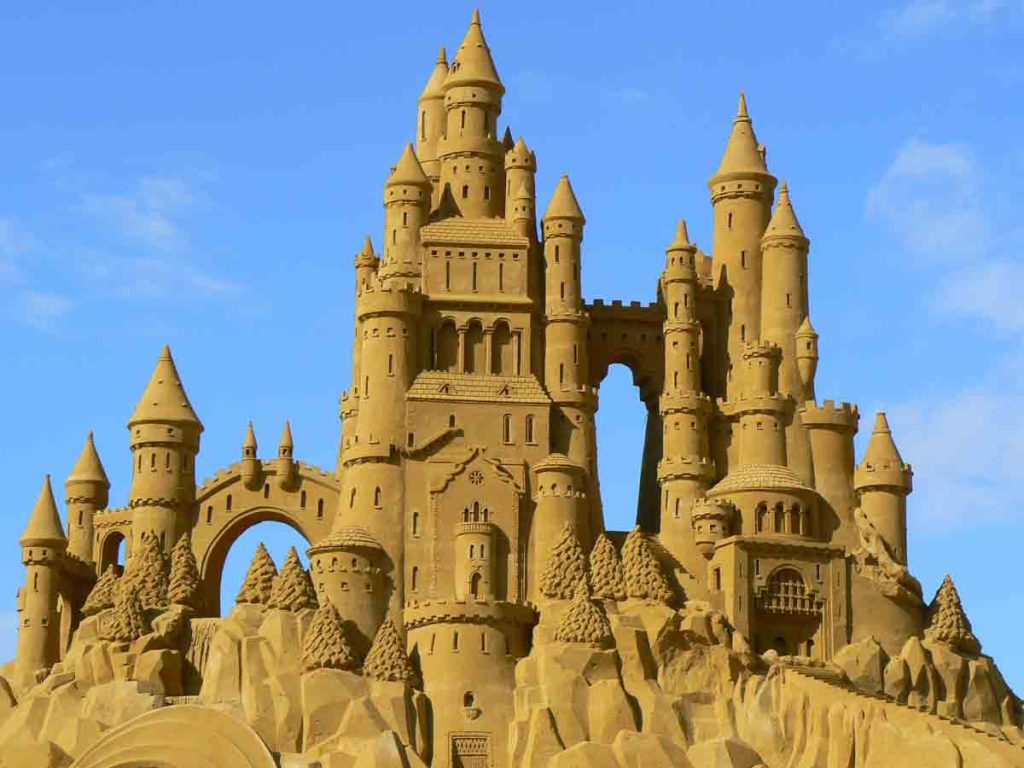

Perhaps you will go to the beach sometime this summer and have a chance to watch children at play in the sand. How engrossed they can get in their projects! When building a sand castle, nothing in the world seems more important than shaping it, embellishing it, and protecting it from the encroaching sea or from other children who might threaten it. This must be a timeless pursuit, for the Buddha offers the following image in a discussion with an elder monk named Radha in the Samyutta Nikaya:

Suppose, Radha, some little boys or girls are playing with sand castles. So long as they are not devoid of lust, desire, affection, thirst, passion, and craving for those sand castles, they cherish them, play with them, treasure them, and treat them possessively.

But sand castles, then as now, are a symbol of impermanence, and will eventually slip into the sea. Equally impermanent are the affections of young children, and even before the tide comes in you may witness the gleeful demolition of what only moments earlier had been so deeply revered. Once the tide of their own attachment has turned, children can destroy with joyful abandon what they have so carefully created. This is something noticed by the Buddha as well:

But when those little boys or girls lose their lust, desire, affection, thirst, passion, and craving for those sand castles, then they scatter them with their hands and feet, demolish them, shatter them, and put them out of play. [SN 23.2]

This is an important observation about human behavior, which can, of course, be applied to a much wider field of understanding. It points to the remarkable insight that meaning is not something existing inherently in things, but is something projected onto things by the application of human awareness. We make things important by investing them with importance, by placing our attention on them, and by treating them as valuable. Sand castles are not universally important or unimportant. When a person considers them meaningful and pays careful attention to them, they become important. When that meaning creating enterprise is withdrawn and turned upon a different object, the sand castle becomes instantly insignificant. I have always liked the way Zhuangzi (Chuang-tzu) put it, “What makes things so? Making them so makes them so.”

The Buddha appears to be using this image primarily to help Radha get “unstuck” regarding the concept of self. When we cling tightly to our bodies, feelings, perceptions, emotional responses, and consciousness, considering them to be profoundly important, the outcome is the sand castle of the self, attended by behaviors that contribute to greater personal and collective suffering. We construct a strong sense of self by investing the five aggregates with the view “This is me, this is mine, this is my self”; when this happens, all sorts of primitive reflexes spring to life, compelling us to cling to what belongs to ourselves and fight off any threat to the things we decide to own. The craving at the heart of this impulse is so fundamental, the Buddha identifies it in the Second Noble Truth as the cause of suffering.

Almost all the difficulties we face, both personally and collectively, are rooted in the fact that we are choosing to define ourselves as the owners of our experience and all that flows from it. Radha is being shown that this is just a choice that one makes, and that an alternative attitude is possible. We can just as easily reverse this if we choose to regard our experience as “This is not me, this is not mine, this is not my self.” If someone walks off with something that does not belong to us, or kicks a pile of sand that we have not invested with our own sense of self, then we tend to be entirely unconcerned and respond with equanimity. This does not make the aggregates disappear, any more than a child scattering her creation makes the sand cease to exist. In fact, nothing in the external world has changed one bit. The difference between suffering and the end of suffering lies entirely in an internal adjustment of our attitudes.

This has wider implications as well, pointing to a second lesson of the sand castles. Much of Western religious and philosophical endeavor discounts personal experience as unreliable and has thus focused on discovering the truth that lies behind appearances. Buddhist thought, by contrast, has been distrustful of the idea of objective truth and has been more concerned with investigating the process of experience itself. These observations have led to the insight, consistent with recent postmodern approaches to many subjects, that meaning is something created rather than discovered.

If this is correct—that value is constructed by people rather than given by nature—then the world we inhabit is a reflection of the quality of our own minds. When greed, hatred, and delusion are shaping the intentions, the actions, and the dispositions of human beings, then the world they create will reflect these attitudes. The dominant economic model might be based on controlled mutual exploitation, an excessive focus may be placed upon building and deploying systems of violent destruction, and the deliberate distortion of information could become commonplace. But if the Buddha’s discovery is accurate, this does not need to be the outcome.

What if it were different from this? What if the central organizing principles of our creations were generosity, kindness, and wisdom? This is not out of the question, since we have these healthy roots in our nature alongside the unwholesome roots. We might just decide to withdraw our care from the things we have created that do such harm and “put them out of play,” as the Buddha said. We might then build an economic model based on mutual generosity, develop and deploy systems of kindness and friendship, and habituate ourselves to honesty in all pursuits. Since we are all just playing in the sand anyway, why not decide to do it differently?

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.