In 1968, a couple of months into first grade at St. Mary’s Elementary School in Ayer, Massachusetts, I notice that my desk is looking kind of funky.

From where I sit, I can peer into the desk of the little girl in the next row: mainly empty, with a neat stack of construction paper, a pair of blunt scissors, a box of crayons, and a few pencils lined up in a groove.

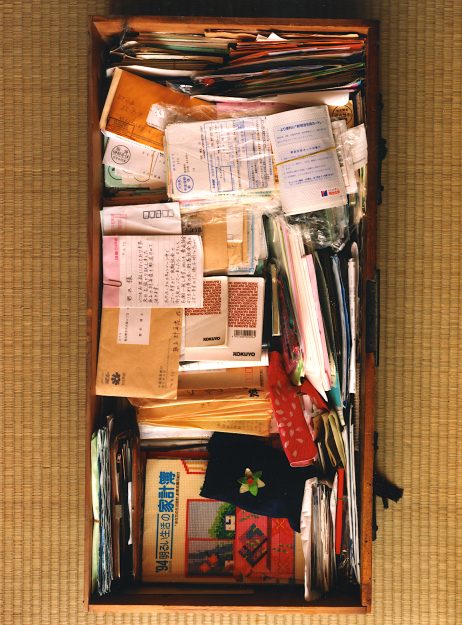

Mine, on the other hand, is overflowing with crumpled, crisscrossed papers—spelling tests, math worksheets, stick-figure drawings, a turkey made from a toilet-paper roll, a laboriously copied excerpt from A. A. Milne, with every p backward: “Christopher Robin went hoppity, hoppity, hoppity, hoppity hop…” When I reach inside to scrabble around for a crayon, my hand lands in a puddle of Elmer’s glue.

I’m not sure how this has happened, and I don’t have a clue what to do about it, but I know it’s not right. Whenever Sister Mary Monica—an immense, stern woman in a black veil and floor-length habit—moves to the back of the room, I hunch over my desk, sliding from side to side in my chair so she can’t see inside. This strategy is futile: Sister stands over me, glowering, while I empty my desk contents into my schoolbag. I am too embarrassed to show my work at home; each of the pages contains a mistake, a misspelled word, a misshapen letter. So instead I cart my heap of clutter back and forth to school with me, papers erupting out the top of my bag.

Thirty-six years later, I am sitting on the floor in my home office, paying bills. My desk is so littered with papers—unpaid bills, unanswered letters, outdated check registers, notes written on napkins and ripped envelopes, a phone number scrawled in eyeliner on an empty paper-towel roll—that I never work there. Instead, I spread out paperwork on the carpet and write on my laptop on the sofa, surrounded by books, folders, and pillows.

And it’s not just my desk—clutter is everywhere I look. In the front seat of my car: three empty juice boxes, a pen with no cap, two ink-stained sweaters, my son, Skye’s, jacket and lunchbox, a toy drum, a yoga mat, the receipts from a photo lab, stubs from my last two paychecks. In my pantry: elbow macaroni spilling out of its package, unlabeled jars of unidentifiable herbs, six bottles of salsa, a box of ginseng tea that was presented to my father by a Korean general in Seoul in 1977. In my closet: shirts slipping off hangers, sweaters spilling out of drawers, a drawerful of socks with no mates, a tangle of nursing bras (in case I have another baby), a wetsuit (in case I ever boogie-board again), a red strapless party dress I wore twice, to great acclaim, a decade ago.

This is not how I want my life to be. I want my home to feel like an ashram or Zen center: tranquil, orderly, radiating mindfulness, with a place for everything and everything in its place, from the incense sticks to the hard-boiled eggs.

I know all the spiritual theories: Housecleaning can be a meditation in its own right, like the ritualized temple-cleaning that begins a day at a Zen monastery. As we bring order to our physical lives, we bring order to our inner being as well. “When the flower arranger arranges the flowers, he also arranges his mind and the mind of the person who looks at the flowers,” goes one Zen saying.

Related: Making Friends with Mess

But I’m as clueless about how to create that kind of order as I was in first grade. I know how to organize an essay, a book, a yoga class. I can sit and watch my breath for hours at a stretch. Through twenty years of diligent practice I’ve slowly begun to shift intractable patterns in my mind, my body, my relationships with other people. But my physical world still looks much as it did three decades ago: papers spilling out of my desk, and me hunching in front of it so the nuns won’t see.

I share this trait with many of my writer friends: a scatterbrained inability to make sense of the physical world, which leads us to retreat into the realm of the imagination. I used to be able to live with this disability, even laugh it off as an eccentricity intimately linked to my creativity. But now, as a working single mom, I can’t afford to spend twenty minutes looking for my car keys or a pair of matching socks.

So I begin ordering books on organization from Amazon.com. The first one, Organizing from the Inside Out, tells me that the basic model for organization is the kindergarten classroom: a home for every object, all organized according to activity, and everything labeled. The second one, Simply Organized!, warns me sternly that if I have two of anything—anything!—I should get rid of one of them immediately. Hmmm, I think, nonplussed. I set both books down, intending to choose between them. A few days later, it takes me twenty minutes to find them.

The problem is, my mind doesn’t seem to work their way. “Group similar items together,” blithely suggests Julie Morgenstern, the author of Organizing From the Inside Out. But it’s not immediately apparent to me, staring into my desk drawer, how to sort three foam earplugs; a heap of paperclips; a nail clipper; a slide-viewing glass; business cards from an acupuncturist, a preschool, and a pet supply store; a broken pencil; an herbal throat lozenge; a pair of swim goggles; and two leaves from the Bodhi tree. Am I really going to spend all morning going around my house creating a proper home for each of these items, one at a time? I stare at the drawer, helplessly; throw away the pet-supply business card; look in vain for a pencil sharpener; stick an earplug in each ear; and turn to the computer to work on the article on yoga and Buddhism that is due next week.

Books in hand, I make valiant efforts to organize my closet, file my papers, clean out my fridge. But every attempt to create order uncovers new levels of disorder and demands systems I’m supposed to go out and buy with time and money that I don’t have: filing cabinets, drawer dividers, laundry-marking pens, a trash bucket that hooks over the seat of my car. And the systems I do manage to construct disintegrate at the slightest provocation. Reaching into the refrigerator for orange juice on the way out the door to yoga class, I knock over a carton of blueberries, which springs open, scattering berries all over the floor; the kitten dashes after them, batting them even further; I drop my yoga mat to grab the kitten, step on the blueberries, and grind them into my socks. Do I race out the door in blueberry-stained socks to get to yoga class on time? Or do I forgo yoga and take off my socks, put them in the laundry, get down on my knees, and pick blueberries out from under the refrigerator, one at a time?

I decide I need professional help. I arrange to write an article for Tricycle on clearing clutter as a form of meditation practice, and begin searching for a Buddhist professional organizer who will inspire me with the connections between filing systems and enlightenment—perhaps a Zen-monk-turned-office manager. But when I google “meditation and organization,” the closest I get is a little book called Clear Your Clutter with Feng Shui by a woman named Karen Kingston, whose website describes her as a psychic and “the leading Western authority on Space Clearing.”

Frankly, I’m a little dubious about feng shui. Years ago, when I was an editor at a yoga magazine, our publisher hired a feng shui expert to help us solve our chronic organizational problems. The consultant hung flags over our office doorways to break up the stagnant ch’i, rang bells to clear the energy in our yoga room, and told us that our interoffice conflicts would vanish if we rearranged our desks so that all the editors’ reproductive organs pointed in the direction of the production department. Dutifully, we followed his instructions, but nothing really improved, and within a year most of us quit.

I want something more concrete. I want someone to tell me how to organize my papers and where to put my shoes, not inform me that my toilet is unfortunately located in the sector of my home that symbolizes “prosperity.”

But to my surprise, Clear Your Clutter is immediately inspiring, despite its somewhat New Agey jargon. “Clutter accumulates when energy stagnates and, likewise, energy stagnates when clutter accumulates,” writes Kingston. “So the clutter begins as a symptom of what is happening with you in your life and then becomes part of the problem itself because the more of it you have, the more stagnant energy it attracts to itself.”

When she comes to my house for a consultation, Kingston walks around the inner perimeter, running her hands lightly over the walls, the furniture, the photos and knick-knacks. Every now and then she pauses to comment or ask a question: “Do you have problems with your left knee?” she asks, passing her hand over my bed. I nod, astonished: yes, my left meniscus is torn. “He doesn’t care about these at all!” she says, touching Skye’s toy box. Again, I confirm that she’s right: Skye has always preferred real objects to make-believe.

Entering my office, she touches my desk and exclaims, “You don’t get much done here, do you?” Embarrassed, I start to explain that I work mainly on the sofa or the floor. “We could rearrange your desk so that you start working here again,” she says. She turns to my designated meditation and yoga corner. “This is a terrible place for a spiritual practice,” she says. “It’s right next to that closet, which is full of stagnant energy—what’s in there?” “All my old journals,” I tell her. “Old photographs, letters, interview tapes . . .”

She nods. “You’ve got to go in there and clear that out.”

“What’s on the inside is not necessarily reflected on the outside, but what’s on the outside always reflects something on the inside,” she tells me, looking around my office. “You can look at this room and say, ‘This is me,’ and then make a choice as to whether you want this to be you or not. When you do clutter-clearing from this standpoint, it becomes a kind of meditation practice, because you are ordering yourself by ordering the environment around you.”

Inspired, I decide to give myself small, incremental assignments: clear and organize one small area of my house each week—a cupboard, a closet, even a single drawer. I take it on as a practice, with a set time to execute it, asking of every item the questions that Kingston gave me: “Do you love it? Do you use it regularly? When you look at it, does it lift your spirits? If you can’t say yes to one of those questions, let it go.” Once a month, I make a trip to Goodwill to give things away: inherited vases and saltshakers, gifts I never liked, clothes I never wear.

With the help of a carpenter friend, I install a bench and a set of coat hooks in my entryway. I attach clear plastic filing bins to the wall by my desk to get the paperwork off the surface. I become aware of objects that I have lived with for so long that they have become invisible to me: the broken clay planter pot on the deck, the pile of screws and springs on the counter over the sink, the unplugged lamp that’s been sitting for months on a bookcase near no outlet. It’s like sitting in meditation and seeing my psyche exposed in all its humbling humanness, its denial, its endless, petty ruminations—and also its flashes of beauty and insight.

As I sort through my bathroom drawers one evening after Skye is in bed—discarding outdated antibiotics, placing toothbrushes into holders—I begin to understand that organizational systems are a practical technology to sanctify the routine tasks that actually comprise most of my day: putting on and taking off clothes, brushing teeth, preparing food, washing dishes. If I view these as tasks to rush through on the way to something more important, they become a crushing waste of time. But from the perspective of Buddhist teachings, each of these activities is a golden moment, an opportunity for full awakening as priceless as a breath on the zafu or a dive into a mountain lake.

I knew this theoretically. But the slow, tedious task of clearing out clutter is a way of bringing this awareness into my body. And to keep clutter from immediately reaccumulating, I discover, I have to slow down—I have to take the time to close a cabinet door, screw the cap on a toothpaste tube, put away coats and backpacks and lunchbox and mail when I walk in the door, without galloping headlong toward some future goal I view as more important.

If I view everyday chores as tasks to rush through on the way to something more important, they become a crushing waste of time. But from the perspective of Buddhist teachings, each of these activities is a golden moment, an opportunity for awakening.

This kind of mindfulness forces a kind of embodied, full-bodied living, with awareness of every gesture. This way of living takes time. But it also gives time back. It gives me back my life, every moment of it.

Related: UnStuff Your Life, a guide to clearing clutter

As I cart a pile of catalogs to the recycling bin, I wonder: is clutter a by-product of living in a culture so soaked in consumerism that it penetrates every corner of our lives with a glut of junk? Most Americans, I’ve read, use only about twenty percent of the things that they own. There’s even a billion-dollar industry of storage units, where people who can’t cram all their possessions into their homes stow them away for a lifetime without looking at them. Surely these are not problems faced by the families I knew in India who lived in one-room houses with six children.

But overconsumption is not the only problem, I decide. My life was untidy back in the days when I lived in one room in a communal house, could fit all my possessions in the trunk of my battered old Chevy, and had to ask friends to bring their own mugs when they came over for dinner. Traveling through India, I marveled at my ability to create clutter in an empty ashram room with just the contents of my backpack.

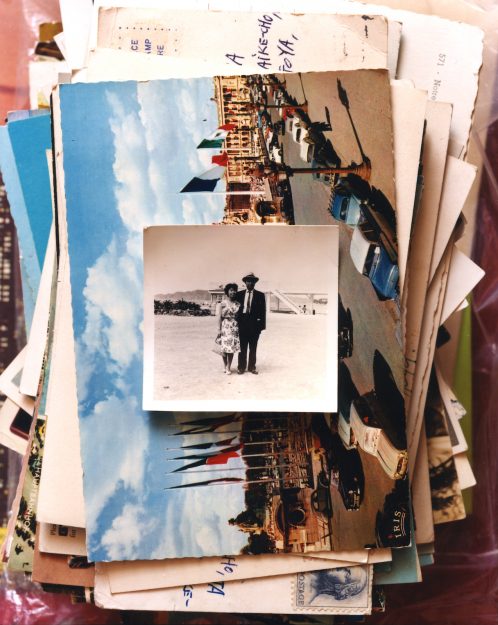

And as I sort through closets and drawers and the garage, I discover that it’s not things themselves that I cling to, but the memories that swirl around them. When prompted, I don’t have trouble discarding sweaters I’ve had since college, inherited pots and pans, hand-me-down cookbooks I haven’t opened for ten years (but have hung onto in the fond hope that I will soon turn into the kind of person who will bake her own baguettes). What’s hard to let go of are the things that bind me to the past, evoking who I used to be and where I have been.

It’s not things themselves that I cling to, but the memories that swirl around them.

What do I do with the leather halter my mother saved in her attic that I won in a cross-country jumping competition with my beloved horse, Kentucky Lady, when I was eleven years old? A few of Lady’s hairs are still caught in the noseband. I never wear it, but will I really discard the green wool Kashmiri shawl I huddled under on the hard wooden benches of sleeper trains through Bihar, the land of the Buddha? A faint whiff of India—cow dung and dust and sweat—still clings to it. And what about my wine-red wedding dress that I wore in a ceremony at Green Gulch Zen Center when I was six months pregnant? That baby died at birth; the marriage is now ending in divorce. What should I do with the dress?

Or what do I do with dozens of sheets of paper with Skye’s colored handprints on them, where our cat tore at them, relics of yesterday’s rainy-afternoon fingerpainting? Do I keep all of them? None of them? One sheet, to be stuffed in a box and pulled out when Skye is a grown man and I am an old woman and the cat is long dead?

Related: The Joy of Letting Go: Spring Cleaning Inside and Out

My grandmother saved—and passed down to my mother—all of the dresses she had made for her in Paris when her husband was stationed there just after World War I. My mother saved a few of them, and passed down one to me. It hangs in my closet—old-fashioned eyelet lace, exquisitely beautiful. I wore it once, to a friend’s wedding eight years ago. Will I give it away?

My office closet is stuffed with things I would carry out of a burning building: a lifetime captured in photo albums and journals that I will carry around with me from home to home until I die—and that, as soon as I die, I want destroyed.

In India, I used to meet sadhus, wandering ascetics in orange robes who had given away everything that bound them to their past, even their names. I heard of a Taoist master in Santa Cruz who, every ten years, gave away everything he owned and started afresh. Is this what the spiritual life demands?

Bringing order to clutter, I begin to see, is not just about putting my spices in alphabetical order. On a deeper level, it’s about balancing the twin poles of spiritual life: cherishing life and holding it sacred, while knowing that it will pass away. It’s about learning to care for the things and people that are precious to me— and, when it’s time, freely letting them go. As Zen teacher Gary Thorp writes in his extended meditation on housekeeping, Sweeping Changes, “The joy comes not from trying to keep things forever, but from keeping them well.”

Bringing order to clutter is about balancing the twin poles of spiritual life: cherishing life and holding it sacred, while knowing that it will pass away.

Learning to bring order to chaos entails, for me, really getting comfortable with the uncontrollable, ever-changing nature of life. It’s about living gracefully and at ease in an imperfect world in which buttons fall off, bath toys get mildewed, socks get holes in them and disappear in the laundry, dresses don’t fit any more. It’s about getting comfortable with a mind that wanders and a body that gets old, in a world of misspelled words and backwards p’s where nothing—from laundry to love relationships—is ever really completed, and where nothing—old photographs, the past, my loved ones, my own memories, my own body—can ever be held onto forever.

I’ve been consciously clearing clutter for over a year now, and I’m still not done. But I am making progress. Every shelf in my pantry is labeled. I only own shirts that I actually wear. I’m writing this at a clean, clear desk in my newly organized office.

Last night, after Skye was in bed, I sat on the floor of my office, sorting through a box of photographs: Skye at six weeks old, fiercely trying to crawl. Me in pajamas on my third birthday, a paper crown on my head. My mother at nine years old, dancing the hula in a grass skirt in Hawaii in the 1930s. My father in his cadet’s uniform at West Point in 1942

I’m not a sadhu or a nun, at least not in this lifetime. I’m not yet ready to let go entirely of my personal identity—not just a disembodied spirit, but the daughter of an Army general and a New England mystic who used to gallop a horse through a Kansas field. So I don’t toss the whole heap of photos into the trash. Instead, I sort through the piles, slipping the most evocative into albums, and letting the rest go.

Someday I’ll know where to put my wedding dress. In the meantime, all around my home, I pick things up, one at a time. I see them for what they are: Saltshaker. Baby photo. Dental floss. Love letter. And I help each one find its true home.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.