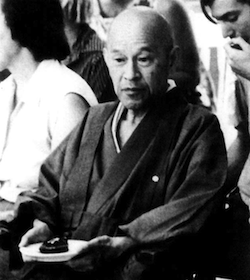

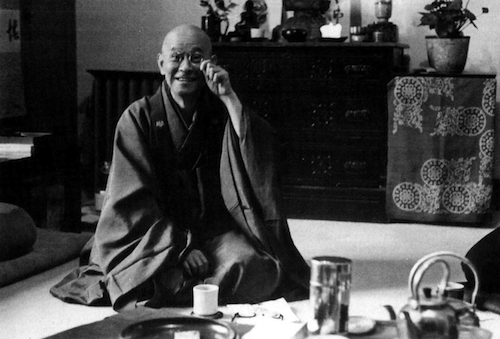

The following is a collection of anecdotes about and teachings by Shunryu Suzuki, a Japanese teacher in the Soto school of Zen, who came to San Francisco in 1959 to minister to a small Japanese-American congregation. He came with no plan, but with the confidence that some Westerners would embrace the essential practice of Buddhism as he had learned it from his teachers. He had a way with things—plants, rocks, robes, furniture, walking, sitting—that gave a hint of how to be comfortable in the world. He had a way with people that drew them to him, a way with words that made people listen, a genius that seemed to work especially in America and especially in English.

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, a skillfully edited compilation of his lectures published in 1970, has sold over a million copies in a dozen languages. It’s a reflection of where Suzuki put his passion: in the ongoing practice of Zen with others. He did not wish to be remembered or to have anything named after him. He wanted to pass on what he had learned to others, and he hoped that they in turn would help to invigorate Buddhism in America and reinvigorate it in Japan.

—DC

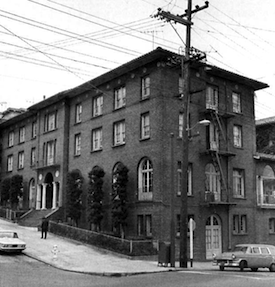

I moved to San Francisco in the winter of 1966 and began attending morning zazen at the San Francisco Zen Center. Suzuki-roshi had been away in Japan during my initial visit to the Center, but, despite having been told very little about zazen and Zen, and with very little encouragement from anyone, I resolved to come to zazen every morning and every afternoon for one year.

My first encounter with Suzuki was when I bowed to him after zazen upon his return to the U.S. I could barely see him through the million thoughts that raced through my mind. A moment later, I was in the hall putting on my sandals. I could see Suzuki in his office, behind the crowd of people on their way out. Still my mind was bubbling. He turned, caught my eye, and smiled, and for the tiniest increment of time everything stopped, and I saw him. It was in small, seemingly insignificant, nonverbal exchanges like this one that Suzuki established contact with students and guided us along our invisible paths. We were almost entirely on our own.

One night in February of 1968, I sat among fifty black-robed fellow students, mostly young Americans, at Zen Mountain Center, Tassajara Springs, ten miles inland from Big Sur, California, deep in the mountain wilderness. The kerosene lamplight illuminated our breath in the winter air of the unheated room.

Shunryu Suzuki had just concluded a lecture from his seat on the altar platform. “Thank you very much,” he said softly, with a genuine feeling of gratitude. He took a sip of water, cleared his throat, and looked around at his students. “Is there some question?” he asked, just loud enough to be heard above the sound of the creek gushing by in the darkness outside.

I bowed, hands together, and caught his eye.

“Hai?” he said, meaning yes.

“Suzuki-roshi, I’ve been listening to your lectures for years,” I said, “and I really love them, and they’re very inspiring, and I know that what you’re talking about is actually very clear and simple. But I must admit I just don’t understand. I love it, but I feel like I could listen to you for a thousand years and still not get it. Could you just please put it in a nutshell? Can you reduce Buddhism to one phrase?”

Everyone laughed. He laughed. What a ludicrous question. I don’t think any of us expected him to answer it. He was not a man you could pin down, and he didn’t like to give his students something definite to cling to. He had often said not to have “some idea of what Buddhism was.”

But Suzuki did answer. He looked at me and said, “Everything changes.” Then he asked for another question.

As a child, Shunryu Suzuki was small yet strong, eager to learn, impatient to do things before he was old enough, sensitive, and kind but prone to quick bursts of anger. And his most notorious weakness was absentmindedness. He couldn’t keep track of anything. Schoolwork and books, caps and coins—whatever it was, he’d leave it at home or at school, wherever he wasn’t.

My habit is absentmindedness. I am naturally very forgetful. I worked on it pretty hard but could not do anything about it. I started to work on it when I went to my master at twelve. Even then I was very forgetful. But by working on it steadily, I found I could get rid of my selfish way of doing things. If the purpose of practice and training is just to correct your weak point, I think it is almost impossible to change your habits. Even so, it is necessary to work on them, because as you do so, your character will be trained and your ego will be reduced.

At the age of eleven, a year earlier than most other boys and against his parents’ best wishes, Shunryu decided to train with his first master, Gyokujun So-on Suzuki, the abbot of Zoun-in, the temple at which his father trained as a boy.

When my master and I were walking in the rain, he would say, “Do not walk so fast, the rain is everywhere.”

Suzuki’s favorite story about his novice days with his teacher, So-on, was a cautionary tale not of selfishness but of discrimination, and of pickles gone bad. At the temple Zoun-in, pickles were made to eat year-round but especially in the winter, when there were few fresh vegetables. There were pickles made from cucumbers, carrots, eggplants, cabbage, and daikon, the giant white radishes. A batch of takuan, daikon pickles, had been undersalted and had gone bad. So-on was told about it. He wouldn’t throw it out. “Serve it anyway!” he ordered. So for meal after meal decomposing daikon were served, and the pickles were getting worse with the passage of time. One night when they could take it no more, after they were sure So-on was asleep, Shunryu and a couple of cohorts took the pickles out to the garden and buried them.

The boys were pleased with themselves, thinking they had gotten away with their prank. But a few days later when they sat down for breakfast at the low wooden table, So-on brought in a special dish—the rotten pickles back from the dead! So-on ate the pickles with them. Shunryu gathered the courage and took the first bite, then the next. He found that he could do it if he didn’t think about it. He said it was his first experience of nondiscriminating consciousness.

Sometimes it is better for your teacher to be mean, so you don’t attach to him. . . . If we have surrendered to our master, we employ all our effort to control our mind so that we may exist under all conditions, extraordinary and ordinary.

When Shunryu had arrived at Zoun-in there were eight boys studying with his master So-on. After the first year there were only four, and midway through the second year they too had gone. So-on was not just hard on Shunryu; one by one the boys had been driven away by his imperious manner and the privations they had to endure with him. Now it was just Shunryu and So-on. He had a lot of responsibility for a fourteen-year-old. Shunryu was lonely without his friends, but he was getting lots of personal attention. That often didn’t work out the way he wanted it to, however.

A hard part of being alone with So-on was that now Shunryu had to carry everything when they went places. One day there was a service in the next valley, a few miles away, and So-on sent Shunryu ahead with a small trunk and a bag of scrolls. At one point along his journey, Shunryu stopped to rest his feet on the way and went down to a riverbank to catch frogs and let them go. Enjoying himself, he forgot the time till he saw So-on crossing a bridge. Shunryu hid till So-on had passed, then took the shortcut over the hill. He arrived huffing and puffing just before his master.

“I saw you under the bridge playing,” So-on said, wagging a finger at Shunryu. “You crooked cucumber. You’re sticking with it but I feel sorry for you. You’re such a dimwit.”

My master always called me “You crooked cucumber!” I understand pretty well that I am not so sharp. I was the last disciple, but I became the first one because all the good cucumbers ran away. Maybe they were too smart. Anyway, I was not smart enough to run away, so I was caught. For studying Buddhism my dullness was an advantage. A smart person doesn’t always have the advantage, and a dull person is sometimes good because he is dull. Actually there is no dull or smart person. They are the same.

“Not always so” was never far away in Shunryu Suzuki’s teaching. He prefaced much of what he said with the word “maybe,” and yet he did not seem at all unsure of himself. When he said this sort of thing, it seemed to come from a deeply rooted strength. He did speak of the absolute, but in enigmatic terms: “There is nothing absolute for us, but when nothing is absolute, that is absolute.”

He talked about the Buddha’s teaching as something fluid and living. “To accord with circumstances, the teaching should have an infinite number of forms.”

He talked about enlightenment, but said, “Enlightenment is not any particular stage that you attain.”

The secret of Soto Zen is just two words: not always so . . . . Not always so. In Japanese it’s two words, three words in English. This is the secret of our teaching. If you understand things in this way, without being caught by words or rules, without too much of a preconceived idea, then you can actually do something, and in doing something, you can apply this teaching which has been handed down from the ancient masters. When you apply it, it will help.

It couldn’t be grasped. It was a paradox, he said, that could only be understood through sincere practice and zazen. The point of his talks wasn’t to tell the truth as he saw it, but to free minds from obstacles so they might include contradictions.

Suzuki thought it was a frequent weakness of Buddhist teachers to cling to a fixed understanding; it was not a weakness of the great Zen master Dogen.

Usually a Zen master will give you: “Practice zazen so that you will attain enlightenment. If you attain enlightenment, you will be detached from everything and you will see ‘things as it is.’” But our way is not always so. What the Zen master says is of course true. But what Dogen-zenji told us was how to adjust the flame of our lamp back and forth. The point of Dogen’s zazen is to live each moment in total combustion, like a kerosene lamp or candle.

“Buddhism is a two-edged sword,” Suzuki said, pretending to swing a sword, turning his wrist, a mischievous smile on his face. “Back and forth, back and forth. Sometimes I strike you with this side and sometimes with that.” He often spoke of the dual nature of reality, but what the two sides were was not so easy to understand. It wasn’t just oneness and duality, but “the duality of oneness and the oneness of duality.” He said one couldn’t speak the whole truth, that there was always another side created by whatever was said, and if his students didn’t get it on their own, they’d get it by the sword that cuts away the side they’re attached to.

We should understand everything both ways, not just from one standpoint. We call someone who understands things from just one side a tambankan. This means a “man who carries a board on his shoulder.” Because he carries a big board on his shoulder, he cannot see the other side.

Often he said, “Just keep sitting.” Very often. Sitting would loosen the grip of what seemed to be reality. But then the idea of sitting or zazen might grip the sitter. Zazen was the first thing he taught, but if it became something too special he’d pull out the rug. Someone would ask for more periods of zazen, and he’d say the schedule was fine as it was. Someone would speak of pain in their legs, and he’d say sit more.

Even “Not always so” was not always so. It wasn’t offered as a formula to cling to.

“There is no question,” a student said, “because there is no answer. Whatever you say will not always be so. So I will just sit.”

Suzuki shook his head.

“No?” the student said. “But you said . . .”

“When I said it, it was true. When you said it, it was false.”

If there is always another side in Suzuki’s teaching, what’s the other side of “not always so”? To look for that, you must take the board off your shoulder.

Almost all people are carrying a big board, so they cannot see the other side. They think they are just the ordinary mind, but if they take the board off they will understand, “Oh, I am Buddha, too. How can I be both Buddha and ordinary mind? It is amazing!” That is enlightenment.

Suzuki talked about the first principle and the second principle from his early days in San Francisco. He said the first principle had many names: Buddha nature, emptiness, reality, truth, the Tao, the absolute, God. The second principle is what is said about the first and the way to realize it—rules, teaching, morality, forms. All those things change according to the person, time, and place—and they are not always so. Suzuki said that talking about Buddhism was not truth, but mercy, skillful means, encouragement. “There is no particular teaching or way, but the Buddha-nature of all is the same, what we find is the same.”

The first principle is not something that the Buddha or other people came up with. Suzuki spoke about Buddha’s sermons in the woods, where he “proclaimed the first principle, the Royal Law.” And he added, “If you think what Buddha proclaimed is the Royal Law, that is not right. The Royal Law was already there before he was on the pulpit.”

Suzuki taught that Buddhism is not the first principle, but is a way to know and express the first principle. Buddha’s teaching can only be thought of as the first principle in “its pure and formless form.”

If you have a preconceived idea of the first principle, that idea is topsy-turvy, and as long as you seek a first principle which is something that can be applied in one way to every occasion, you will have topsy-turvy ideas. Such ideas are not necessary. Buddha’s great light shines forth from everything, each moment.

Suzuki always made clear that the first principle is beyond discrimination or knowing in the ordinary sense, in the way that relative truth is known.

Bodhidharma said, “I don’t know.” “I don’t know” is the first principle. Do you understand? The first principle cannot be known in terms of good or bad, right or wrong, because it is both right and wrong.

Once Suzuki divided up the zendo: those on the right were to ask questions about the first principle and those on the left about the second. If someone asked about the wrong principle, they’d have to move to the other side of the zendo. Nobody actually changed sides, though they had a good time trying to present their understanding of the first principle. In the end it seemed like there was nothing at all to say.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.