Although I have on occasion glimpsed what I took to be the light of wisdom in some mutt’s orbs, and while I’m convinced that when asked if a dog had Buddha-nature, Master Joshu answered not wu but wuf, I’ve been disinclined to take a dog as my guru—for the simple reason that dogs are the most deeply domesticated of animals and I prefer my teachers free and wild.

Some might attribute this aversion to pethood, literal and figurative, to a longtime penchant for sniffing out the left-handed path. Others would argue, with some justification, that it stems from the misfortunes I suffered twenty years ago when I tried to teach a monkey to do light housekeeping. In point of fact, however, my affinity for the untamed spirit is a direct result of my having, as a baby, been carried off by dingoes.

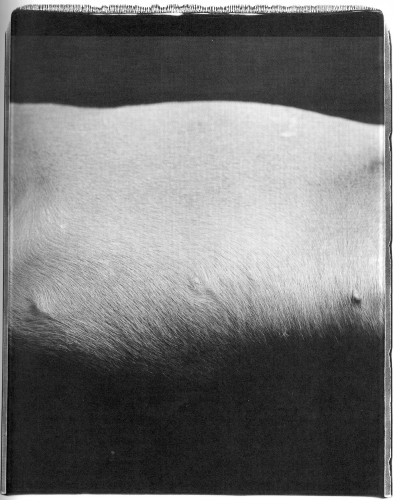

Oh, yes. My anthropologist parents were doing fieldwork in the outback, when one evening at dusk, a female dingo with eyes like electrified lemon drops stole into our tent, sunk her fangs in my rompers, and dragged me away to her pack’s funky den, where she suckled me to surfeit and rolled me around playfully in the bloody feathers on the floor of the lair.

I had lived among the dingoes for only two months before I was discovered by a friendly Aborigine and returned to my bipedal mom, but I was with them long enough to absorb a measure of their language and I retain some dingo vocabulary to this day (since it’s virtually impossible to transcribe, even phonetically, I shan’t attempt to inflict any on the poor reader), and that translinguistic ability has given me an unusual perspective on canine consciousness.

Whenever I see some stick-chasing, slippers-fetching, sofa-sleeping obedience school graduate wagging its tail, begging for a meatball or slavishly searching for new ways to ingratiate itself with its owner, I close my eyes and picture a barren hilltop far off in the wastes, where a collarless, leashless dingo (or wolf or coyote) engages in a dialogue with the moon. And I imagine that I have a pretty good idea of the dingo’s side of the conversation.

Now, a principle tenet of every pet dog’s security-oriented philosophy is, “If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” On the other hand, I know the dingo’s view to vacillate from, “It’s always broke and you can never fix it” to “There’s nothing to break so what is it that you’re fixing?” It’s my suspicion that all of Zen resides in the arc between those two poles. Of course, I could be barking up the wrong lotus blossom.

In any case, I will always favor the teacher who lifts his leg on dogma, who even bites the hand that feeds him, over one who’s panting to be scratched behind his ears.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.