I grew up in Northport, New York, on the edge of the Long Island Sound. As my family tells it, I learned to swim before I could walk. By the time I was 5, I was on a swimming team, and pretty shortly I was learning to sail, too. When my brothers and I went to the south shore of the island, where enormous waves pounded into shore, we were fearless. We couldn’t get enough. As a teenager, I worked as a lifeguard, and by the time I was married, my affinity for the ocean was so deeply rooted that when my husband and I bought a house in northeastern Connecticut to be near his job, I couldn’t stand it: two years and one day later, we moved back to be near the water again.

Many years ago, on a Labor Day weekend, when most of the lifeguards had left for school, a friend and I went to the beach and swam out to a sandbar about 500 yards from shore. On the way back in, we were caught in a fierce riptide. As we swam parallel to the shore, waiting to be released by the rip, my friend began to tire. I knew what to do: I told her to lie on her back and rest for a few moments, and then we swam in. Once onshore, we saw another woman caught in the rip, in real trouble. I dove back in the water, warning her not to grab on to me, or we’d both go down. I circled around behind her, placed her in a loose cross-chest carry, and helped lead her in.

So I thought I knew what to expect from that beach when I returned the next day, on my own. I swam out to the sandbar, but by the time I was above it, I wasn’t able to touch bottom—it was a day later, and the tide wasn’t far enough out to expose the sandbar. I was heading back toward land when I was caught in the rip again. Instead of swimming parallel to shore, as I had known to do since I was a child, I was gripped with fear. I pushed straight toward the beach, exhausting myself with the effort and overwhelmed with panic. The people onshore appeared to be three inches tall, as if they were receding further and further away.

In those instants of panic, my life literally flashed in front of me. I saw myself as a baby getting a bath in the kitchen sink. I could see my brothers playing baseball in the yard, and I could smell the scent of summer. And then, I had a vision: it was the cover of the East Hampton Star, with a headline announcing: “Local Teacher Drowns,” followed by another line: “And she was such a good swimmer.” I thought, “I’m not doing this. This is not happening this way—that’s not going to be the headline.”

I don’t know what happened next. I don’t know if the rip let up, or if I let go of my panic, but something happened and I was able to make my way in.

Yet that fear that I felt in my body didn’t completely disappear. That panicked sense of drowning stayed with me and recurred, at surprising and unrelated times, for years. The following winter, I was trekking through hip-deep snow in a nature conservancy near my home, and felt that same drowning sensation. It was remarkable how similar and frightening the sensation was, and I was quickly reminded of my summer experience.

And then the sensation began to appear in my meditation practice. I had always had difficulty with concentration, but over years of practice, I was beginning to drop down and quiet my mind. Now, just as I would start to get into a state of calm spaciousness, I began to feel the drowning sensation welling up. It came in the form of heat rising up from my abdomen and blooming into my chest to the point where I thought I was suffocating. I would try to stay with it, to stay with the breath and watch the feeling arise and wait for it to pass away, but it would hijack me, and I would become very unsettled.

This went on for a long time. I went to the Insight Meditation Society for a 17-day lovingkindness retreat, and I continued to manage the sensation. I described it to teachers in interviews, but nothing changed, though I continued to try my best to work with the sensation. Finally, I described the phenomenon to my teacher, Thanissaro Bhikkhu, with whom I sit every year at the Barre Center for Buddhist Studies. “I think it’s pitti— rapture,” he said. Some people, he explained, are struck by fear or extreme discomfort when they finally begin to settle down into concentration.

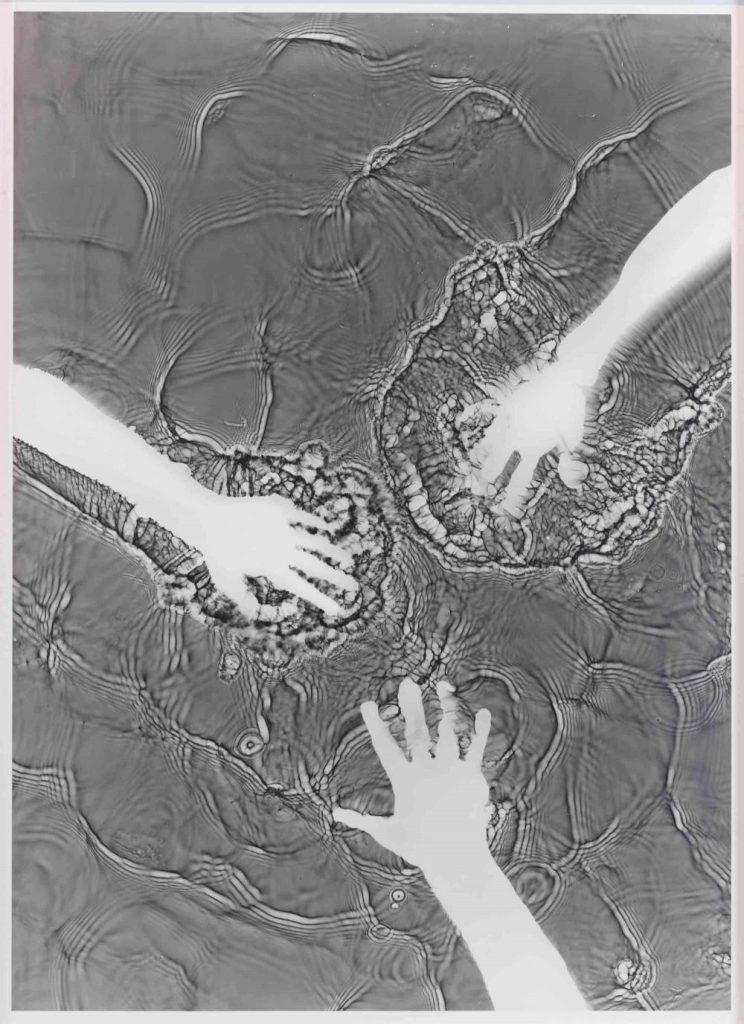

He suggested that I envision my breath moving into my hands and feet—that I try to siphon off some of that energy, away from my core and out to another part of the body. Then I should think about the elements. Since I felt a lot of heat, I was to think of water—and, I immediately had the thought, of lying in water.

It seemed ironic to picture myself submerged in a body of water when my entire being was fighting a fear that felt like drowning. But little by little, I found a way through concentration to make it work.

There’s a beautiful peninsula on the Peconic Bay called Jessup Neck. It’s a wild place, jutting into the bay and beckoning to migrating birds, especially terns. I began to visualize myself as that peninsula, surrounded by water. If I focused on the higher ground of the peninsula—the center of my body supported, but lying on the water—and the edges of my body dipping into the clear liquid, the drowning fear, the sense of claustrophobia or suffocation, would release. I placed my focus on the cool water within reach, a spacious sky, and the sound of the terns . . . and it helped. I began to understand how the elements—earth, wind, fire, and water—could be used to balance and quiet my whole system.

I’m still swimming in the ocean regularly, though over these many years I still contend with my fear of drowning. I’ve come to see that my panic in those moments years ago prevented me from skillfully enlisting the tools I knew would get me safely to shore. Rather than protect me from danger, my fear put me at risk. Ultimately, the same goes for the fear I experienced—and sometimes still do—on the cushion. As I knew when I helped save the woman from drowning, the key is not to grasp, or swim against the tide, but to go along and allow the elements to balance. By skillfully and strategically letting go, I can safely reach the shore.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.