Knowing how much is enough when eating…

This is the teaching of the buddha.

—Dhammapada

“Knowing how much is enough when eating.”

It sounds so simple. Yet how often the matter of “enough” trips us up. For much of the world, getting enough to eat is the problem. Here in America we eat too much. Two-thirds of the population is overweight, nearly a third clinically obese; meanwhile, our ideal of physical beauty keeps getting thinner and thinner.

Increasingly, we exist in a love-hate relationship with our bodies and in a state of conflict over food. Denying the body with one hand, we stuff it with the other—then second-guess every morsel we consume. Whether we are ordering a five-course dinner at the Four Seasons or eyeing a plate of Krispy Kremes, our hunger seems to have far less to do with nourishment than with the gratification of desire.

We weigh ourselves against impossible standards, and when reality falls short of our expectations, self-doubt—even self-hatred—is quick to follow. Judgment for dietary indiscretions is swift and harsh: a recent print ad for Kellogg’s Nutri-Grain health bars suggests how culturally ingrained this view has become. A bikini-clad model is shown reclining pinup-style, an enormous, icing-covered croissant balanced on her hip. The tag line says it all: “Respect yourself in the morning.” Food—the primordial form of nurture—is becoming a primordial source of suffering.

Ironically, the more we focus on the body, the more alienated from it we become. Increasingly, we resemble Mr. Duffy, the protagonist of James Joyce’s short story “A Painful Case”: “He lived at a little distance from his body . . .”

From a Buddhist perspective, however, the body is not the problem. Rather, it is our thoughts about it that undermine our sense of well-being. What is required is a shift in perspective that allows us to understand the nature of craving and to welcome the body, whatever state it is in. When we can relate to the body and our appetites with compassion and acceptance, we will no longer have to live at such a distance from ourselves.

Why do we eat, anyway? Clearly, physical hunger is not the only drive. Eating soothes emotional discomfort and offers escape from unpleasant feelings of anger, disappointment, agitation, fear, pain, sorrow, loneliness, or simply boredom. In times of stress, nearly everyone turns to food. CNN reported that in the days after September 11, consumption of ice cream and sweets rose dramatically in New York City.

Often we associate eating with happy times and try to recapture good feelings by consuming certain foods. We eat out of habit: “What’s a movie without a bucket of popcorn?” We eat to be polite: “I don’t want to insult my hostess.” Sometimes, we eat in response to a vague feeling of lack, or a fear that there won’t be enough in the future: “I’d better take one before they’re all gone,” we reason. “It’s just a cookie, after all.”

For many people a cookie is just a cookie. Eating it brings a moment of enjoyment—or, at worst, guilty pleasure—then they give it no more thought. For compulsive overeaters, however, a cookie is the culinary equivalent of a loaded gun: one bite can send them spiraling into a hell realm of insatiable desire.

The Buddha identified three poisons that constitute suffering: craving, aversion, and ignorance. Overeating is among the most insidious of cravings, a form of suffering that carries much shame. In a society that worships svelte bodies and self-control, we are merciless toward those who appear to have neither. The overeater, faced with desire that seems difficult, if not impossible to extinguish, sees no recourse but denial. However, retreating behind ignorance of the consequences only perpetuates the cycle of mindless eating, yo-yo dieting, and morning-after recriminations—and deepens its hold. Like a drunk suffering a hangover, a compulsive eater fresh off a binge has one overriding thought: Help! How can I stop this self-defeating behavior?

Food—the primordial form of nurture—is becoming a primordial source of suffering.

This is the very issue the Buddha addressed in his teachings on the nature of human suffering. We all want happiness, he observed, but we chase after it in ways that are sure to bring us pain. One of the Buddha’s most profound teachings is the law of dependent origination, which expresses in exquisite detail the twelve interdependent links in the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, spelling out how suffering arises and escalates. The principle of dependent origination (paticca samuppada in Pali, the language of the early Buddhist texts) sheds light on repetitive and compulsive behavior, showing why—and how—the stranglehold of conditioning makes it so difficult to change. Through this teaching we see that in the presence of certain causes and conditions, certain effects are inevitable:

When there is this, that is.

With the arising of this, that arises.

When this is not, neither is that.

With the cessation of this, that ceases.

–The Buddha, from the Samyutta Nikaya

In Tibetan Buddhism, the cycle of dependent origination is depicted graphically in traditional thangkas, or symbolic paintings, by the Bhava-Chakra—the Wheel of Life, or Wheel of Samsara. The iconography of the Wheel of Life illuminates the truth that compulsive behavior doesn’t arise spontaneously; the seeds are planted long before the moment of acting out. In the language of addiction and recovery, it is said that the “slip”—the lapse into compulsive behavior—happens long before the person takes the first bite of food or sip of liquor.

The twelve images on the outer circle of the thangka depict the coexisting conditions that entangle us in the endless cycle of human suffering. In examining these factors we see not only how suffering arises but also—this is critical—where we can intervene and make an inner shift to arrest the cycle.

The first link is ignorance—avijja in Pali. Ignorance is represented, appropriately, by a blind man walking with a staff. If we are deluded—if we fail to see our thoughts and actions clearly—we are bound to repeat our behavior. A key symptom of uncontrolled or unhealthy eating is denial that it is causing any problems. We ignore the reality that eating to get rid of discomfort only leads to more discomfort.

Related: If You Give a Buddhist a Cupcake

The literature of Overeaters Anonymous, a program of recovery from compulsive eating that follows the Twelve Step model, sums up this process: First we were smitten by an insane urge that condemned us to go on eating and then by an allergy of the body that insured we would ultimately destroy ourselves in the process. This is the same principle set out in an ancient Chinese proverb: Man takes a drink, drink takes a drink, then drink takes the man. Until we can awaken from delusion and acknowledge the consequences of our actions, the pattern of self-destructive behavior will continue and even escalate.

The next link in the cycle of dependent origination is characterized by volitional formations (sankhara), also known as karmic impulses. This stage refers to the mental conditioning—habitual thinking—and karmic patterns that inevitably lead to certain actions. When we are in denial, we make up stories to rationalize our behavior. Each time we act on one of those stories, we strengthen our belief in it, thereby reinforcing the behavior. The thangka image for this link is a man fashioning clay pots.

I once had a client who weighed over three hundred pounds and had had numerous operations on her knees. She persisted in believing that her ongoing knee problems came from having no time to do yoga, not from being vastly overweight. This is an extreme example, but how often we make excuses for overindulging: “Well, there’s no point in starting a diet now; it’s the holidays!” “I know I shouldn’t eat this, but you only live once”; “Just one couldn’t hurt”; “Things have been so tough, I deserve a treat.” Rationalizations like these lash us to the wheel of samsara.

The third link in the cycle is consciousness (vinnana), the faculty of knowing, depicted by a monkey swinging through the trees. (Here, the monkey is a symbol of the ever-changing mind.) This link refers to our perception and awareness of sensations as they arise, as well as to our mind state—angry, dull, or yearning, for example—which influences how we interpret sensory information. What gets our attention in the present is colored by our impulses and innate disposition—our habits of thought developed in the past.

Consciousness co-arises with the fourth link, mind and body (namarupa), pictured in the thangka as people in a rowboat. Consciousness shapes how the mind and body function, as in this familiar example: A woman who was dieting and feeling good about her progress got on the scale one morning, expecting a weight loss. Instead, the scale registered a two-pound gain. Frustrated and angry, she thought, “I’ll never lose weight, so why bother?” Her intention to stick to her diet dissolved, and she went out and bought a pastry for breakfast.

The state of the mind and body influences the fifth link, the six senses (salayatana), represented on the thangka by a deserted town (also commonly depicted as a monkey in a house with six windows). Here we encounter an important distinction between Buddha-dharma and Western psychology. In the West, perception is associated with the five senses (seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, and touching) and their corresponding sense organs. In Buddhism, mind is considered a sixth sense organ, or “sense door,” because it continually interprets the moment-to-moment input of the other senses. Our thoughts and opinions about our sensory experience influence our perceptions and responses, as the Dhammapadaso eloquently explains:

The thought manifests as the word;

The word manifests as the deed;

The deed develops into habit;

And habit hardens into character;

So watch the thought and its ways with care,

And let it spring from love

Born out of concern for all beings . . .

As the shadow follows the body,

As we think, so we become.

When a stimulus meets a functioning sense organ, there is contact (phassa), the sixth interdependent link, symbolized by a man and woman lying together in an embrace. Stimuli are constantly moving through us and around us, without our conscious awareness or volition. Contact brings awareness of a particular sense impression to the foreground. For example, let’s say a man has just come out of his boss’s office after a particularly trying meeting that extended well past lunchtime. As he passes the receptionist’s desk, he suddenly sees a basket of candies sitting there that he has never noticed before, and reflexively scoops up a handful.

Whenever there is contact, the seventh link–feeling (vedana)–arises concurrently. (The image for this link is a man with an arrow piercing his eye.) Feeling, according to Buddhist thought, is associated with one of three possible sensations: pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. There is a deeply conditioned reflex in all organisms to move toward what is pleasant and away from the unpleasant. Some people eat to avoid bad feelings. Some continue eating even when they’re full, either because the food tastes so good or because the process of eating is so pleasurable. A client of mine who was going through a difficult period bemoaned, “There’s so much I can’t do right now, but I need some kind of gratification. The chocolate looks so good. Even though I know I’ll regret it later, I’ll eat it anyway.”

Links three through seven–consciousness, mind and body, the six sense bases, contact, and feeling–are intricately interconnected, arising automatically without our conscious control. Unpleasant feelings naturally lead us to look outside ourselves for a way to feel better; pleasant feelings lead us to look for a way to continue feeling good. That search sets the conditions for the eighth link, craving (tanha), to arise.

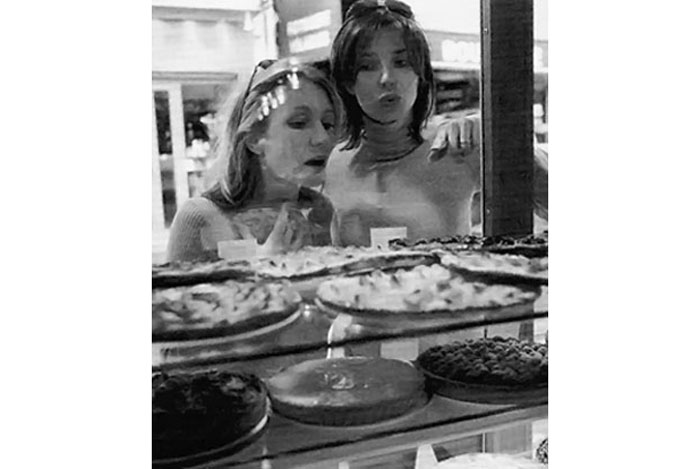

Here’s a simple example of how this process unfolds: One person walks by a bakery without even noticing it. Another walks by and notices the smell of fresh bread, but continues on without stopping. A third person smells the bread and feels a rush of well-being: the scent triggers the memory of a delicious dessert she ate the previous week. Though late for work, she stops in front of the bakery window and debates whether or not to go inside and buy something to eat.

Here we stand at a critical crossroads, where there is still room for conscious choice. The split second between having a feeling (vedana) and giving in to craving (tanha) is the optimal moment to intervene and break the cycle of samsara. This is our opportunity to awaken and move away from self-destructive behavior. With strong intention and the proper tools, we can develop the strength and concentration to withstand temptation.

But what happens if we ignore this opportunity and give in to desire? In recovery circles one often hears the warning: Stay away from people, places, and things that trigger the urge to eat. This is skillful advice, but hard to follow. Unlike alcohol, or drugs, or tobacco, food is not a substance we can avoid altogether; it is essential for our survival. One frustrated dieter summed up the problem when he snapped: “You have to eat and not eat at the same time!” Daily life is filled with constant reminders of food, including our own thoughts about eating.

Related: Food for Enlightenment

Any powerful association can set off a desire to eat. It may be the smell or sight of a favorite food, or even the sound of someone chewing. A description of a gourmet meal can elicit euphoric recall and intense craving. For a food addict, the most mundane event can be a trigger: one young woman has only to see someone snacking from a brown paper bag and she is off on an eating binge.

The Buddha called craving the root of suffering. Tanha literally means “thirst”; the thangka symbol for this link is a man taking a drink, but it could just as easily be someone eating. At this stage on the wheel of life, the attachment to feeling good and avoiding discomfort begins to trap us in an endless cycle of painful behavior.

Once we give in to craving, we are catapulted immediately into clinging (upadana), the ninth link Here, the mind becomes fixated on the object of desire. It grasps. The image on the thangka is of a monkey in a tree, grabbing for fruit. All possibility of choice fades. As one overeater described it, “Even though my mind is aware, the body seems to have made up its own mind.”

The trance of grasping sweeps us into the tenth link, becoming (bhava), depicted in the thangka as a pregnant woman. Now, with the first bite, the overeater’s thoughts constrict, hardening into identification with the drive to eat. All other aspects of one’s being gradually become engulfed in a fog of “more.”

With the eleventh link, birth (jati)–pictured as a woman giving birth–the compulsion to eat is firmly entrenched. Having lost the will to try to break the cycle, the overeater surrenders to every impulse; the first bite inevitably gives rise to the next. Yesterday’s relationship with food has set the karmic template for tomorrow’s. The twelfth link–aging and death (jara-marana)–is assured. This is the death of possibility, of options. The image for this stage is an old man carrying a corpse on his back. Now the urge to eat is conditioned, and suffering is guaranteed, as the wheel of samsara turns once more. The overeater’s feelings of physical discomfort are accompanied by tortured self-recrimination: I can’t believe I did it again.

The Buddha, of course, did not leave us caught in the cycle of suffering with no way out. Just as suffering arises moment to moment, so too does the possibility of freedom from suffering, he said. The Buddha taught from his own experience how to be free of unhealthy attachments: though we cannot escape painful feelings, we can choose how to react to them. Centuries later, Bill W., the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, echoed that theme in the Twelve Step program of recovery. To break the cycle of craving, we must see the truth as it is, however uncomfortable that may be.

For anyone watching their food intake, life seems to involve an ongoing internal debate: Should I eat this or not? But the real question, according to the Buddha, is not Should I? It is What is happening right now? Looking deeply into our experience, without judgment, we can explore the sensations, thoughts, and feelings that lie behind our desire to retreat into the ready comfort of food.

Through mindfulness training, we can ease the grasp of delusion, allowing us to experience the truth of impermanence, the workings of karma, and the power of intention. Desire narrows our awareness till we see only what we crave; mindfulness helps us see other possibilities. As we observe that our cravings–no matter how strong–eventually pass, we no longer feel compelled to act on them. We discover where in the cycle of craving we can effectively intervene. When mindfulness is strong enough to create space between stimulus and reaction, the karmic attachment that leads to automatic behavior is weakened, giving us a chance to make wiser choices. Even our most intractable habits can be changed.

But even with a strong mindfulness practice, there may be times when it is difficult to break a conditioned response without additional support. The Buddha spoke of the importance ofsangha–like-minded people with the same aspiration. To change harmful patterns, it is helpful to be around others who understand the pull of craving and are doing their best not to give in to it. For an overeater, “sangha” could mean a sympathetic friend, or a professional counselor, or a group of people with a shared intention, such as Weight Watchers or Overeaters Anonymous.

The message of the Buddha is that we are no longer doomed to be prisoners of our compulsions. When we take refuge in the Triple Gem–the Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha–we find a safe haven from the false promise of food, and open ourselves to wisdom, compassion, and the promise of liberation. We take refuge in the Buddha both as an historical figure who found true freedom and as the seed of possibility that exists within us all. We take refuge in the Dharma–the universal truth, the Way. And we take refuge in the Sangha, the community of spiritual companions who support our efforts to be free.

May all beings be at peace with their bodies.

May all beings be at peace in their bodies.

How To Say No

The Buddha gave many teachings on what to do about distracting thoughts. Certain practices can be adapted to help us when food cravings arise. What is important to remember is that in any moment, we have options; the practice is to find the skillful means for each situation.

Intention is the key; everything else rests on this. We all have different triggers for overeating; know yours. Also keep in mind what your goals are—not to eat, not to go off your diet—and which foods are important for you to avoid. Consider which emotions make you feel the most vulnerable, and when you feel that way, turn to meditation, affirmation, or visualization for support. Then, set and hold the intention not to pick up a trigger food.

Substitute the thought of food with the thought of something more important. For example, visualize the face of someone you love, or feel gratitude for all the gifts you have in your life. Imagine yourself engaged in some pleasurable activity; see yourself on that vacation you’re looking forward to, for example. The Buddha taught, “As we think, so we become.”

Mentally follow the entire process of giving in to the desire to eat. See the whole cycle from beginning to end. If you take the first bite, where will that lead? What has happened in the past? How will you feel the next day? If, instead, you refrain from eating, how might you feel?

Ask yourself: What do I really want right now? What is the feeling behind the urge for food?

Stop whatever you are doing at the moment you feel the urge to eat, and do something entirely different: stretch, yawn, get up and walk, make a phone call. Even a simple action can break the trance.

Cultivate willingness to ask for support. In Buddhist practice, we take refuge in the sangha to support us in our practice. For support in avoiding destructive eating, we can phone a friend who understands our intention, for example, or join a support group for overeaters. On an everyday level, “support” might simply mean asking the waiter to remove the basket of rolls from the table.

Maintain nonjudgment. If you overindulge, don’t punish yourself. You will only make your suffering worse. Instead, observe your behavior with a compassionate heart. Then remember the instruction that is the foundation of meditation practice: Begin again, with wise intention.

Meditation to Work with Craving

Start by taking a few deep breaths. With a half smile on your face, imagine that you are inhaling a sense of calm and exhaling any tension, any thoughts about food. Allow the breath to return to normal. Bring your attention to your belly and the inner sensation of the breath rising and falling in that area.

When thoughts of eating or of a specific food come to mind, note “thought arising.” Become aware of the pleasant or unpleasant feelings that accompany the thought, then shift your attention back to the body, experiencing whatever physical sensations arise. Cultivate moment-to-moment awareness. Not resisting, not forcing. Just this, just this.

Thoughts come and go. Feelings come and go. Allow yourself to experience the transient nature of thoughts and feelings, welcoming everything that arises as just this, not me, not mine.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.