Edo

Art in Japan 1615-1868

The National Gallery of Art: Washington, D.C.

Nov. 15-Feb. 15, 1999

The Art of Twentieth-Century Zen

Japan Society: New York City

Nov. 19—Jan. 10 1999

Traveling the U.S. through

March 11, 2000

Audrey Yoshiko Seo and Stephen Addiss

Shambhala Publications: Boston, 1998

232 pp.; $65 (cloth)

To Zen Buddhists, the most spectacular object in the National Gallery’s exhibition of the art of Japan in the Edo period might well be the broad bladelike tower rising improbably high from the crown of a black war helmet. Made in the eighteenth century for a daimyo to don on his obligatory excursions to and from the shogun’s castle, this bold lacquered-wood signboard is inscribed with characters for the five cosmic elements: earth, water, fire, wind, and—at the top—mu, or emptiness.

To wear mu like a banner, extravagantly, as though marching with complete abandon into the abyss of death, must have made the helmet’s owner, the fervently Buddhist daimyo Matsudaira Sadamoto, a striking figure on his annual march to Edo. It is also a reminder of how Japanese Buddhism merged seamlessly with the 1,200-year panorama of warfare and cultural politics that preceded the Meiji Restoration of 1868.

Mainly, though, it was the sublimely material aspects of the relatively prosperous and peaceful Edo period that interested curator Robert T. Singer of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He has organized this show for the National Gallery around five categories—Style, Samurai, Work, Travel and Landscape, and Religion—but these arbitrary divisions often result in curious stress fractures. Matsudaira Sadamoto’s helmet is in the Samurai section, for instance, although one could argue that it is the most religious object in the exhibition, particularly since, strangely, the Religion section does not display a Buddha.

We have to go to the catalog to understand this decision. In the view of modern historians, Singer maintains, Buddhism in the Edo period was in an “intellectual, spiritual, and moral decline.” The shogunate, to counter Christian missionaries, shut the country’s borders and began regulating and promoting Buddhism, killing its vitality. Instead, Singer finds liveliness in folk ritual, parades, festivals, and pageants (seen in cinematic detail in several bright, gold-strewn screens). He cites a “playfulness that borders at times on the burlesque,” as in a scroll from Chotoku-ji ablaze with the red flames of hell, or two lifelike carved rakan, disciples of the Buddha, from Rakan-ji. He also likes the raw, earthy spirit exemplified by the mountain-dwelling ascetic Enku, who made a vow to carve 120,000 bodhisattvas—which he did with such speed that they appear to be chopped with the Edo equivalent of a chainsaw.

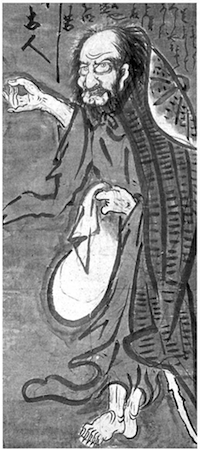

Singer’s interest in material culture—a traditional art-historical position—directs him to view Japanese religion from the outside. But maybe there are other sides to the story. The Religion section opens with a wall of sober black-ink Zen paintings, one of them by Hakuin Ekaku, the poet, painter, and Zen master who, by pure force of character, revived Rinzai Zen in Edo Japan. Hakuin painted many portraits of Bodhidharma, the first Zen ancestor in China; in this case he has put some of his own thorny, fierce, slightly crab by disposition in to Bodhidharma’s puckered face and staring, egg-sized eyes. That single-minded resolve need only be present in one or two teachers per generation for Buddhism to survive any apparent lull.

Next to Hakuin’s portrait is a rivetingly famous image, perhaps the best known of all Zen paintings: Sengai Gibon’s brush drawing of a circle, triangle, and square. Possible interpretations point to the three vehicles (Hinayana, Mahayana, Vajrayana) or the three bodies of the Buddha (Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya, Nirmanakaya). But visually speaking, the three geometric elements could also represent the nature of form itself: its differentiation into separate identities that arise from a common origin and interpenetrate (overlapping at their edges). Their simplicity and clarity survive all commentaries.

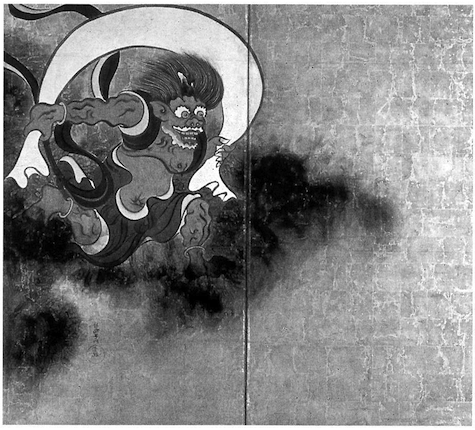

Black-ink Zen, one suspects, might—in the curatorial view—be low on audience appeal. The exhibition quickly returns to bravura painting, including a brilliantly colored six-panel screen, in a surreal, pre-comic- book style, depicting Taoist immortals in communion with various demons on their mystic mountain. Oddest of all is “Vegetable Parinirvana” by Ito Jakuchu, a painter who was the son of a greengrocer. In this lovingly skillful ink painting, the Buddha is a giant daikon reclining on a basket, and all his attendants are vegetables. It’s a beautiful work, suggesting a reverence for the Buddha-

nature in all growing things. But in the absence of the Buddha himself, the exhibition appears either obsessively cautious or deeply uneasy about religion.

The Edo show may well represent one pole of American museological attitudes toward Buddhism: art-historical reserve bordering on paralysis. “The Art of Twentieth-Century Zen,” an exhibition at the Japan Society in New York of brushwork by contemporary Japanese Zen masters, is its opposite: a sophisticated appreciation of the transmission of the dharma from master to student, expressed through art. Curator Audrey Yoshiko Seo of the College of William and Mary in Virginia, has enlisted the help of scholar Stephen Addiss. Both authors, while not themselves practitioners, have been closely involved with Zen and understand it as a living reality.

Their show displays the witty, lighthearted yet serious work of fourteen contemporary Japanese Zen masters who are also master calligrapher-painters. The lineage begins near the onset of the Meiji with the turn-of-the-century reformer Nakahara Nantenbo, who died in 1925. It ends with Fukushima Keido, abbot of Tofuku-Jiin Kyoto, and the only one of the fourteen still living. Fukushima’s teacher, Shibayama Zenkei, also makes an appearance: It is a teacher-student dialogue that repeats throughout the century.

“To make a painting requires a lot of zazen,” said Zen master Yuzen Gentatsu. He was writing during a period when Buddhism was being persecuted and nearly obliterated by the Meiji Restoration, which linked the power of the emperor to state—supported Shinto. Buddhism survived its eclipse and eventually prospered in Japan because of the dedication of its abbots and teachers, argue Seo and Addiss. Their excellent catalog doubles as a fluent chronicle of monastic Buddhism in modern Japan, picking up where Edo fears to go.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.