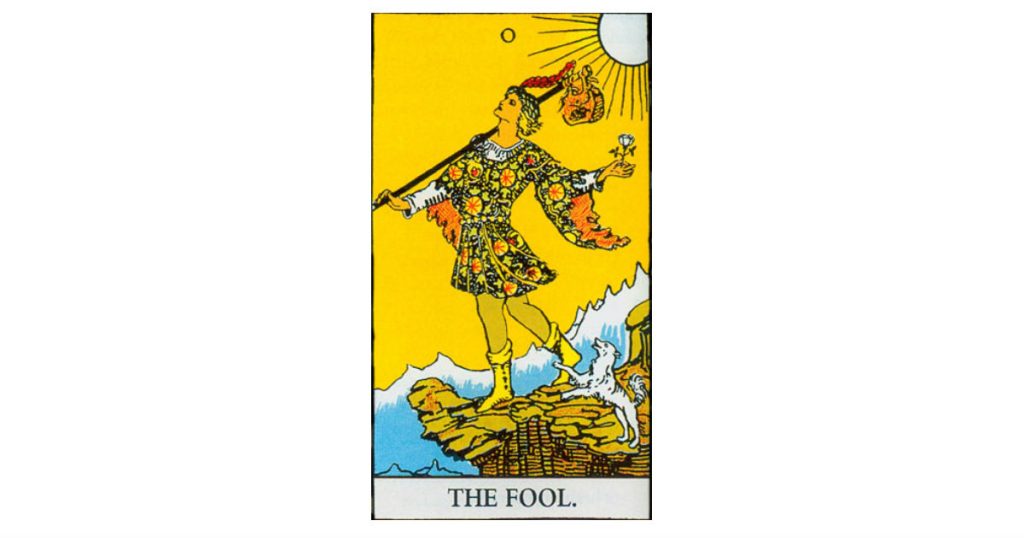

Being a Fool lets the cat out of my bag, the wind out of my sails. The word comes from the Latin follies, meaning “windbag, a pair of bellows.” The pleasure of being foolish lies precisely in the freedom it gives from self-importance and social expectations; the freedom from striving, from the pressure to impress others, to do things the way others do them.

A fool is simply not responsible in the way most people are. He knows he is ultimately not responsible for the way things turn out. He isn’t weighed down by the weight of the world. He knows the world won’t descend into chaos if he takes a nap for half an hour.

Being the fool is not the same as acting the fool: you can’t decide to be playful, or foolish, for an hour a day, as if it were yet another task to add to your campaign of self-improvement. It’s rather the result of a relaxation of the rules and goals that you normally run your life by. A softening of the beliefs that hold up your world and your idea of who you think you are. The pleasure of foolishness lies in large part in the absence of self-consciousness; in the self-forgetting that comes in a moment of abandon.

Whenever I’m in a country where bargaining is the usual mode of transaction, I have enjoyed the poker game of going back and forth in order to walk off with my prize—a carpet, a painting, a piece of ceramic—for the lowest price possible. I would spend a day for the sake of reducing the price by the equivalent of five dollars. But more often than not I would walk away with not just my purchase but also with a tinge of regret. Sometimes I would feel downright mean. There had to be a balance somewhere between walking off feeling I had been taken advantage of and walking away feeling strangely guilty. Then one day in Istanbul I fell instantly in love with a carpet in a small shop near the Topkapi Palace—right in the heart of the tourist district, where prices are always grossly inflated. The elderly vendor looked at the rug, flipped it over, and quoted a figure. I came back with something near half of his quote. He smiled and came up with a number somewhere between his and mine. I accepted without another word. It was all over in forty-five seconds. I was ecstatic, as much for the ease, the simplicity of the transaction, as I was for the rug.

We both smiled, shook hands, and I walked out of that shop with my carpet and a light heart. For someone else, this would have been normal. For me, with my radar for being made a fool of, this was a breakthrough. A highly pleasurable one. And if I had been had, this time I truly didn’t care.

We may run the risk of losing face or being taken advantage of when we let the fool in us have some say, but we may also be exposing ourselves to the possibility of genuine connection to other human beings, to the wisdom that comes out of left field, synchronicity, and unlikely meetings on street corners. And you never know, we may even be opening the door to love.

♦

From the book Seven Sins for a Life Worth Living, © 2005 by Roger Housden. Published by Harmony Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.