The world learned of the cult called Aum Shinrikyo on March 20, 1995, when deadly sarin gas was released in five Tokyo subway stations. Eleven people were killed and 5,500 injured. It was subsequently learned that Aum had released sarin once before, killing seven and injuring fifty in the town of Matsumoto in 1994. Both attacks would turn out to be meager in scale compared with the violence on Aum’s drawing board.

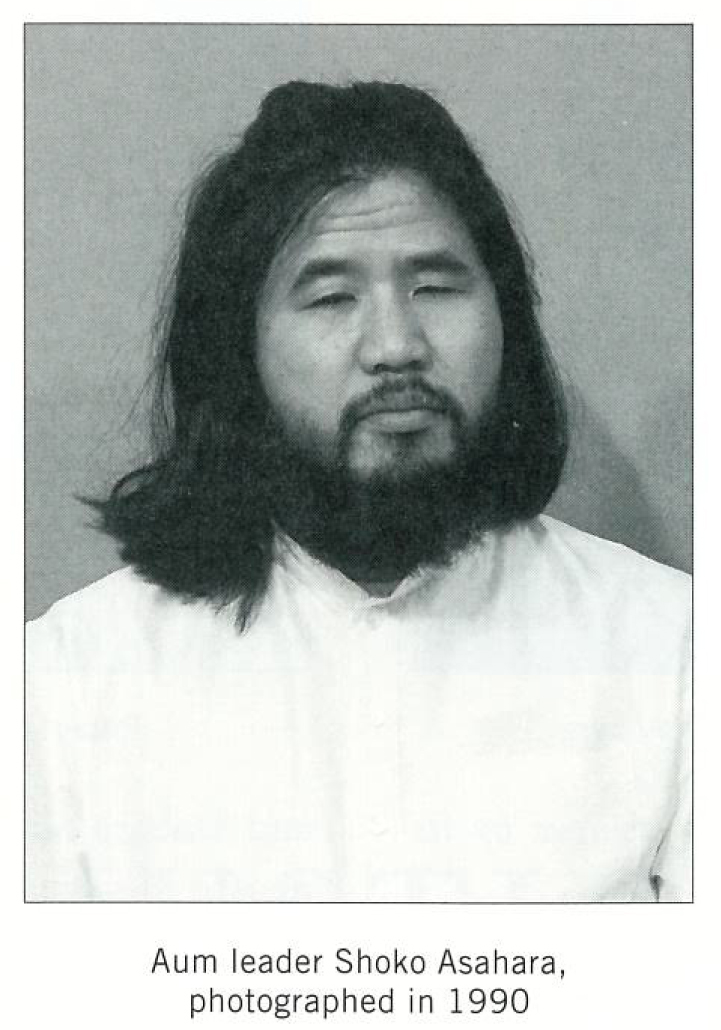

Aum was founded in 1987 by a partially blind former yoga teacher known as Shoko Asahara. Born Chizuo Matsumoto in 1955 in a small village on the island of Kyushu, Asahara is currently on trial in Tokyo for the subway attack. His ideology, a volatile mixture of Buddhism, Hinduism, and Christianity, shares elements with other new religions that have been founded in Japan in this century. It attracted many young Japanese, often from the professional classes, who were disenchanted with the country’s values during the period of the economic boom.

Aum is not the first example of spiritual ideas gone toxic, but in the violence of its vision, it is by far the most dangerous seen to date, and its “Buddhism” is a disturbing reminder that no vision is independent of the mind in which it takes root. -Lawrence Shainberg

Robert Jay Lifton is Distinguished Professor of Psychiatry and Psychology at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and at John Jay College, where he directs the Center on Violence and Human Survival. His books have explored such varied subjects as Nazi doctors, nuclear weapons, and the Chinese Cultural Revolution; his most recent title is Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial(Putnam/Grosset). His previous work in Japan has included extensive research among survivors of the Hiroshima bombing. He has been conducting research on Aum Shinrikyo since 1995.

Lawrence Shainberg is a writer and consulting editor to Tricycle. His most recent book is Ambivalent Zen: A Memoir (Vintage).

SHAINBERG: What did Aum hope to achieve by its horrific acts?

LIFTON: Aum represents a new human danger: it was an apocalyptic cult with both a fascination for and the capability to acquire ultimate weapons, in particular what they called the “ABCs of weapons”—atomic, biological, and chemical. They had stockpiled chemical and biological weapons and had sought to acquire nuclear ones. The attack on the subway was actually an improvised response to news that a police raid was on the way. In fact, their planned release of sarin gas was scheduled for some months later, in November. Asahara had originally wanted to make seventy tons of sarin. They had bought a helicopter and sent one of their members to America to learn how to fly it so they could dispense the gas from the skies over Tokyo. That could have killed people in the hundreds of thousands, even millions. That was to be their means of setting off World War III. And thereby initiating Armageddon and the end of the world. That was their modest ambition.

SHAINBERG: How many members did it have at its peak?

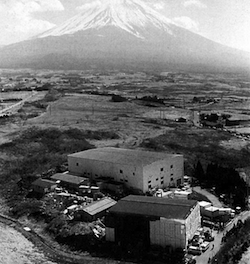

LIFTON: It’s usually thought that there were 10,000 people in Japan and 30,000 in Russia—it’s a strange statistic. But of those 10,000, fewer than 3,000 were shukke, monks or full-time devotees who lived in isolated communities.

SHAINBERG: Did they have a following in this country?

LIFTON: Just a sprinkling. They had a little office here, and Asahara came here a couple of times, but he was quoted as saying that Americans were almost impossible to convert because their bad karma was fifteen to twenty times heavier than that of the Japanese. But I do think it’s important to recognize that Aum was part of a worldwide end-of-the-world impulse. It’s not just the Japanese. Everywhere, on every continent, there are religious or political groups that embrace the idea of the end of the world. Where Aum was different was that, rather than simply anticipating the end of the world, they actively sought to bring it about.

SHAINBERG: Instead of waiting passively, the guru took action to make his predictions come true?

LIFTON: It was mainly Asahara’s idea, but it was embraced by his followers. The end of the world was an integral part of their concept of salvation. That’s why Aum has to be seen, as uncomfortable as this is for many of us, as a religious problem.

SHAINBERG: But why did they want to destroy the world? How did that connect with their religious vision?

LIFTON: Aum sought to cleanse the world of all its defilement by destroying it. Only then could a pure, new people and spiritual level be attained in the world. The apocalyptic message itself stemmed from a vision Asahara described in which the god Shiva appeared and commanded him to lead an army of the gods in a struggle of light against darkness. Of course, Shiva is a Hindu deity, but then, Aum was eclectic. As you know, there’s a lot of Hinduism in Tibetan Buddhism, and Aum’s overall focus was on intense forms of Tibetan Buddhist practice. When Asahara began to train his followers, it was with a set of practices that were largely taken from the Tibetan tradition.

SHAINBERG: Can you say what those practices were?

LIFTON: There were various kinds of meditation, including so-called standing worship-moving from a standing position to abject prostration and doing it 1,000, 10,000, 100,000 times-he took this from the preliminary practices of the Nyingma school. But I think the most significant idea he took from Tibetan Buddhism was phowa [a practice whereby a dying person’s consciousness is liberated from the body through the top of the head]. Phowa is to be learned from a guru and to be applied when one is in the process of dying, for the sake of enhancing one’s own spiritual movement toward Buddhahood. There’s uncertainty about the extent to which in actual tantric practice it might have been extended toward the performing of some violent act. But the way that it was interpreted by Asahara emphasized that in Tibetan Buddhism there are some very rough demands. If your guru says you must kill others, you must kill them. Because that means that their time to die has come, so it’s the right thing to do.

SHAINBERG: In other words, it’s an act of compassion.

LIFTON: Yes. The capacity to insist that everyone in the world must be killed, to purify the world, comes from a world-hating vision of religion. The world is defiled and hopeless in its bad karma. It’s an act of compassion to kill such people—that is, ordinary people like you and me—because it enhances their immortality, or their subsequent reincarnation, or their journey to the Pure Land, however you want to put it. Not everybody in Aum believed this in such stark terms, but Asahara pressed this point of view, and as he became more unstable, he pressed it more.

SHAINBERG: How did he get to Buddhism in the first place?

LIFTON: He read extensively 111 Tibetan and tantric Buddhism. And in the early eighties, he was a member of Agon-shu, one of the so-called Japanese New Religions. Thousands of these have been founded in Japan since the nineteenth century, and a whole run of them following World War II. Certain of his ideas about the persona of the guru and the heritage of Tibetan Buddhism can be traced back to Agon-shu. After leaving Agonshu, he went to the Himalayas, where in 1986, he claimed to have achieved final enlightenment.

SHAINBERG: Has he discussed what he meant by final enlightenment?

LIFTON: Not really; he just declared it. One of the problems with final enlightenment is that it’s such a subjective claim. Because he didn’t belong to any reputable religious institution, he wasn’t responsible to anybody or anything. You know, you can say, as many young Japanese do, that Buddhism in Japan lacks life. It seems deadened to them. But if you’re a Japanese Buddhist and you belong to an institution, there are limits to what you can do. That’s not so when you form your own religious organization that has no ties or requirements involving anybody else.

Related: Obsession and Madness on the Path to Enlightenment

SHAINBERG: Do we know who he studied with in the Himalayas or what his experience there was? Was he just wandering there?

LIFTON: He visited a few people there. He didn’t really study with anybody. He just checked in and discussed his religious life, as he did with the Dalai Lama.

SHAINBERG: He met with the Dalai Lama?

LIFTON: The Dalai Lama received him courteously, probably even warmly. And probably said things to him that he wishes he didn’t say. Asahara had pictures taken, and then quoted the Dalai Lama as saying, “What I’ve done for Buddhism in Tibet, you will do for Buddhism in Japan.” The Dalai Lama was asked about it later on and denied having said these things and said he just received him in a hospitable way. Asahara also visited religious leaders in Sri Lanka and other places, had his picture taken with them, and claimed they received him as a great spiritual master. But the Japanese press followed up his visits and interviewed a number of the people he’d described as having acclaimed him. One of them said, “We had a meeting and then he came back to me a week or two later and said he had achieved final enlightenment. I thought that was rather surprising because it usually takes close to a lifetime to achieve enlightenment.” But the act was convincing to his followers. And, in some way, it was convincing to himself. There’s a strange psychology with some people that enables them to believe in their own version of events and simultaneously maintain a whole manipulative, con man side. The combination can be persuasive.

SHAINBERG: Any can man becomes more effective the more he believes in himself Was anything in his belief justified?

LIFTON: He demonstrated a rather unusual talent for yoga from early on. A lot of people came to him initially for yoga instruction, many of them professionals or young university graduates who wanted something spiritual in their lives. This talent for yoga was a very important basis for what came later. It became inseparable from the Buddhist practices or Buddhistlike practices that he taught And he had a certain superficial brilliance in articulating various Buddhist, Hindu, and Christian concepts. Asahara was an extraordinarily effective religious teacher as well as a murderer.

SHAINBERG: How did he get from religion to murder?

LIFTON: One account of his direction, which is the usual one, is that Aum Shinrikyo, like Agon-shu, could initially be seen as a typical example of a New Religion. It held a lot of interest for spiritual seekers and got a lot of positive response. It was only later, once people began to resist Aum in various ways—parents’ groups claiming that it was brainwashing their children and so on—that it came into conflict with mainstream society; then Asahara went bad and broke down, and caused a lot of trouble.

SHAINBERG: What’s your version?

LIFTON: I think a truer version of the sequence is that he was visionary and megalomaniacal from the beginning. He was an extreme paranoid, and paranoids are notorious for functioning at a high level of intellectual capacity. Especially if they can continue to control their immediate environment, which is their whole world. When that control is threatened, for one reason or another, they tend to break down. And that’s what happened with Asahara when his cult came under siege. Details started to leak into the press in the late eighties about Aum’s illegal acquisition of land and the finances of its members and other crimes. The most notorious case was the murder of a lawyer named Sakamoto who was taking the lead in exposing Aum’s illegal behavior. He was killed in 1989 along with his wife and baby. And there were lots of other murders that took place between ’89 and ’95. In fact, it’s not quite known how many people they killed. It could be up to a hundred. Many people are missing from within Aum. Now, it’s true that most of the ordinary members did not know about the weapons or the plans for violence. But they too had to ward off evidence that something was wrong—although just when the change occurred in Asahara is not easy to say. Because it was not a complete change: the potential was always there. There was always the dimension of the con man in him as well as the effective religious teacher.

SHAINBERG: Have you heard descriptions of him as a teacher?

LIFTON: Yes. His disciples describe him as extraordinarily dignified and composed. One man I interviewed described how struck he was by the contrast between the dignity that never left him when he was a teacher in those early years and the way he has fallen apart in the courtroom.

SHAINBERG: Now he’s fallen apart?

LIFTON: Oh, absolutely, and he’s acting psychotic, bizarre, accusing the judge of sending waves of radiation to his brain. I think it’s possible that he had become psychotic even before the end of Aum. Months before he launched the actual attack he was talking about being attacked by sarin gas, suffering from acute fever, looking for spies within Aum. He always had an apocalyptic orientation; but he became more monolithic, more insistent on his prophecies of doom. And his project for realizing those prophecies.

SHAINBERG: Do you think there’s a relationship between the way that Asahara’s own fantasies seem to have bled over into the world outside, and the condition of a world in which media is making fantasies concrete for us all the time?

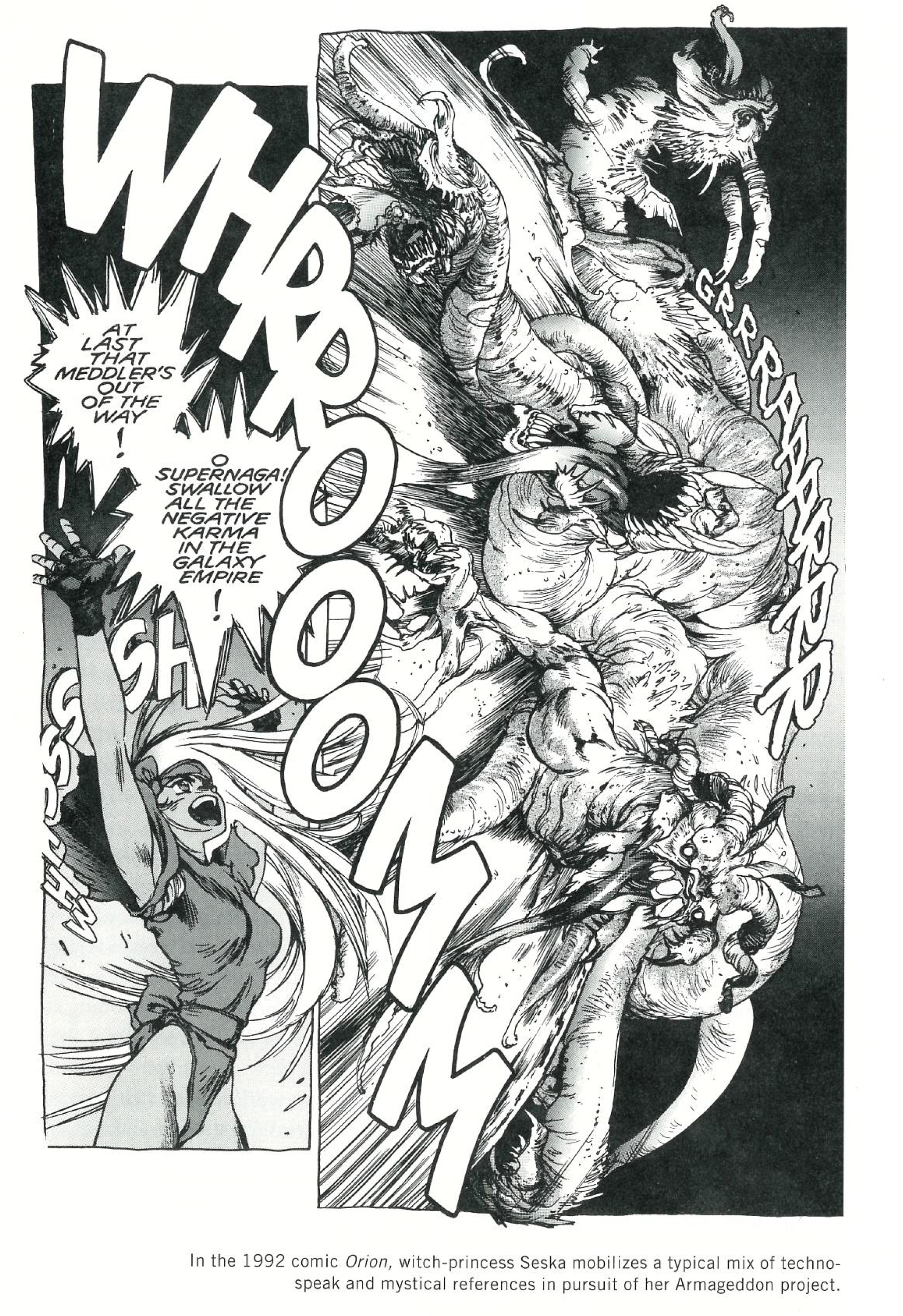

LIFTON: Asahara’s relationship with the media was a two-way street: if there were fantasies going out, there were also fantasies coming in. Aum, like certain other New Religions, was media-savvy; it took full advantage of Japan’s media saturation. Asahara was a frequent television guest. In one of the blurbs for his book, it says he was, in effect, your all-purpose genius—”He wrote music, he made films, he was a great religious figure and a prominent television personality.” So there is a way that the media could be seen as a conduit between Asahara’s imagination and outer reality. His ideas certainly found a fertile environment. Ever since World War II, the Japanese media have thrived on apocalyptic fantasy. They feature all kinds of stories about the earth being threatened, or the earth being blown up, or the earth being involved in an enormous confrontation with an evil planet; and usually there are Japanese saviors who struggle to sustain the earth or who come into a postapocalyptic world and offer services to the human remnant. And World War II is very much a factor in these stories. It may be no accident that a violent cult that wants to bring about Armageddon appears first in Japan, the only country that’s experienced the atomic bomb.

SHAINBERG: Did that kind of imagery get reproduced in the fantasies of Asahara and his followers?

LIFTON: There’s a vision that I’ve heard from several former members of Aum. It starts with a scene of absolute devastation. Big fires, cities crumbling, parts of them falling into the sea—Armageddon combined with a nuclear holocaust. Then, in some tiny corner, there’s a quiet spiritual area in which a small group of Aum practitioners are going through their meditative practices. World-ending images or fantasies have always been with us; they’re part of the human repertoire. Ordinary people have these fantasies in dreams all the time. But the weapons that could make this fantasy come to pass didn’t exist until recently. That’s what’s extraordinary.

SHAINBERG: So is the degree of credibility Aum members were encouraged to place in these fantasies.

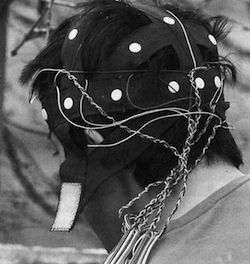

LIFTON: The place was full of visions. I talked to many people who referred to intense mystical experiences. Enormous emphasis was placed on meditation and oxygen-depriving breathing exercises. And later, there were drugs, including LSD. People had frequent visionary experiences, many of which had to do with seeing bright lights—that seemed to be their mystical logo. From very early on, the word among people who had undergone training with Asahara was that it was extraordinarily intense, extraordinarily rewarding.

SHAINBERG: Rewarding in what sense?

LIFTON: Almost to a person, they describe experiencing high energy. And that energy itself took on a kind of mystical feeling because it really meant life power, immortality power. And they miss it, despite everything that’s gone on in Aum. One former member I spoke with in Tokyo told me, “I’ve been going to the trial every day. I’m learning things that I hadn’t known about Aum. But it’s funny, I had such enormous energy when I was in Aum.” I asked him: “What about since then?” He told me: “Well, it’s gradually petering out.” And I’ve spoken with others who were more actively nostalgic for that energetic state that they had never known prior to or after Aum. But I should also make it clear that not all the teachings were on this rarefied level. He would also give sermons or little lectures about understandable, everyday lifestyle issues. “What’s the point of worrying about death? It’s karma, it’s a silly thing to worry about. What you want to do is look at your life. Is there some sort of vacuum in your life? Do you feel you live in a corrupt social situation?” And his analysis of Japanese society could be quite hard-hitting—that it’s lockstep authoritarianism in both educational and corporate structures. It made sense to people who were themselves antagonistic toward Japanese society and felt themselves to be excluded from it. They were often young people who were viewed as weak because they couldn’t stand up to the demands of the Japanese rat race. So Aum gave them a home and spoke to them on this nitty-gritty basis as well.

SHAINBERG: So you’re saying Aum offered its members a sense of community, it offered them a spiritual anchor, and on top of that it offered mastery of these special practices that were generating high energy?

LIFTON: Yes, but if you put it that way, it sounds pretty calm and matter-of-fact. What it offered was fierce intensity. Not simply a community, but a transcendent community of special people who alone had the highest spiritual aspirations-increasingly devoted to the teaching that everybody outside of Aum was defiled, hopelessly doomed by their bad karma. That’s why, when things started to go wrong, their commitment was so internalized that they couldn’t condemn the guru. They couldn’t separate themselves from him. Even now, it’s extremely hard. People I’ve talked to will say things like, “Asahara’s a criminal, he betrayed me as well as others.” But then in their next breath, they’ll tell me, “I must have had a tie to him in an earlier life. Maybe he was my guru back then.” He used the whole concept of karma in a highly manipulative way. Even in esoteric Buddhist or Tibetan teachings, as I understand it, karma may be the result of past lives, but you still always have an opportunity for redemption through good behavior. Karma doesn’t wipe out your potential for good, so to speak. But with Asahara, it did, unless you followed him. You were weighed down, you were dominated by your bad karma, that was his teaching.

SHAINBERG: Unless you followed him.

LIFTON: Yes. When I studied “thought reform;’ or so-called brainwashing methods, in totalistic systems, I found that the key to controlling other human beings seemed to be in controlling their guilt and shame mechanisms. Well, controlling their karma goes one further than that-it includes guilt and shame because you can feel yourself to be bad or condemned on account of what you’ve done in past lives. But the guru also assumes control over your destiny, over what you are and what you can be in an absolute way.

SHAINBERG: And your next lives!

LIFTON: And all of your next lives, that’s right. He’s knowledgeable about your past, he’s offering you a fascinating, transcendent present, and he’s asserting control over your future. And all future lives.

Related: Reincarnation: A Debate

SHAINBERG: He has also lifted any sense of personal responsibility from you. He’s liberated you from all banal responsibility in this lifetime.

LIFTON: Yes. Your only responsibility is toward following his training so completely that you merge with the guru. It’s a total annihilation of self, but it’s also an assumption of his megalomania. Total self-surrender is rewarded by shared grandiosity. Several former members I interviewed still struggled with that grandiosity—it was palpable. Because they are these very special people who alone are in possession of the truth that is destined to be transmitted to the whole world following World War III and Armageddon. They are to be not just the leaders, but the arbiters of this new cosmic dimension. And in return for such a promise, they surrender. Annihilate their own self in the service of merging with the guru self. Many of them experienced visions that illustrate this belief.

SHAINBERG: Can you describe these visions?

LIFTON: One young man saw a pyramid-like structure that was made of human beings. At the top of it was Asahara sitting like a divinity. Like the Buddha. And he, the person who was having this vision, was drawn toward the top of this pyramid, toward the guru, by some inexorable force. He moved closer and closer until the two of them merged and he was no longer just himself, he was Asahara, and Asahara was no longer just Asahara, Asahara was also he. And then he asked Asahara—but of course it was also Asahara doing the askin—”ls this true emptiness?”; and the Asahara figure, but at the same time also he himself, answered: “Ah. So you experience it for the first time.”

SHAINBERG: This is all consistent with Zen or other Buddhist doctrines which aim toward a relinquishing of ego, losing separateness from the teacher and becoming one with him—but here it’s turned into megalomania. Can you say something about the scenario that transforms what is essentially a vision of total humility to one of egomania?

LIFTON: Well, the humility was never there for the guru, so, you see, there’s a terrible problem for the practitioner in discerning megalomania in his or her guru. The paradox of Asahara, I think, is how the leader of a religion could both genuinely convey and teach spiritual practices—mainly Buddhist in this case—and, at the same time, be corrupt from the beginning. One can’t dismiss either his deep corruption or his genuine religious achievement.

SHAINBERG: That’s a hard paradox to contain.

LIFTON: Yes, it’s hard for me even to say that because I don’t like to call it an achievement, but at least it was perceived by followers as such. It’s not always easy to tell a compassionate guru from a murderous one. Part of the problem is that states of exaltation have a certain consistency and appeal no matter what their source. Or, to put it another way: He who enables someone to achieve high states that are perceived as authentic has gained tremendous influence over him. That’s true whether it’s a great Zen master or somebody who turns out to be not only a fanatic but also a criminal, as was the case with Asahara. A genuine religious experience, in this sense, requires a kind of enhancement of the disciple’s vulnerability by opening his self up to formlessness. And Asahara seems to have had a powerful ability to induce visions of formlessness on the way to mystical experience through kundalini yoga or other methods. The danger lay in his ability to exploit this vulnerability.

SHAINBERG: What we call “formlessness” in Buddhist tradition means, among other things, the experience of total insecurity or groundlessness. Ideally, in a Buddhist framework, if the teacher and student trust each other and can work together-if the teacher is an authentic teacher-he can help the student tolerate this vulnerability and see, as we would say, the unity of form and formlessness. But if one persists in maintaining a distinction, then the experience of formlessness is only going to create a desperate need for form. Buddhist literature is full of statements to the effect that if the practice is explored in any kind of partial manner, it can turn to poison. In some ways, what you’ve described with Asahara is a horrible caricature of this point; but you can also see it as a metaphor for all institutional religion. At the source, it’s a vision of formlessness, but the vision evolves to impose a new form and subsequently to corrupt and abuse it.

LIFTON: Aum arrogated to itself the claim of all truth for all human beings. But it also radically separated itself from a life-affirming or human-centered morality by setting up a barrier between itself and ordinary people. In fact, there were two sets of barriers—two sets of absolute distinctions. On the one hand, there was the barrier between the Aum people and the ordinary people, who were hopelessly defiled. They were defiled in the first place because they had had no contact with Asahara. The second level of radical differentiation was the barrier between Aum members and Asahara himself. Even now, quite a few of them feel guilty and fearful over having “broken the pipeline”—that’s their phrase. One side of their mind still holds to the guru as the only source of truth and purity in the world. And that makes many of them wonder whether maybe history will prove him right—that all this was for a higher purpose that we ordinary human beings are incapable of grasping, but that he understands, in order to achieve a higher level of human evolution.

SHAINBERG: It’s quite extraordinary when you think of it corning out of Buddhism, which begins with a denial of precisely that kind of discrimination: the fundamental idea that all beings as they are have Buddha nature. There is no such thing as defilement in terms of a Buddhist vision-in any true Buddhist vision. But he appropriated the doctrine that essence is formless, and he turned it inside out.

LIFTON: All religions have the possibility for destructive behavior. You know, I spoke with a Buddhist priest who helped me a great deal in my research. He has been extraordinarily giving in his way of dealing with former Aum members. Nevertheless, when he talked about Aum, he would say: “This is not Buddhism. Buddhism is about other things; compassion is central to our theory and practice.” Well, that’s true; it’s not Buddhist compassion, certainly-but you can’t say it’s not Buddhism.

SHAINBERG: There’s an expression in Buddhism that Buddha and the devil are never more than a hairbreadth apart. That’s why it’s critical to examine the way that Aum Shinrikyo springs from Buddhist understandings.

LIFTON: That’s what so many of the former disciples are trying to do. And they have a very hard time. It’s partly that the whole experience has been so disrupting that their lives have been not only interrupted, but shattered; and, of course, there’s the reality of being made pariahs in Japanese society. But I also think that it’s very hard for them to extricate themselves from the Aum version in which they were immersed so deeply and come to another Buddhism. Many are simply casting about. But they do struggle with the tradition. They read the Buddhist scriptures, they look to Buddhist teachers, they do all kinds of things to rediscover a different Buddhism.

SHAINBERG: Has Aum left a lesson for the rest of us?

LIFTON: Yes. There is no more threatening mix than fanaticism and ultimate weapons. Religion can be dangerous.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.