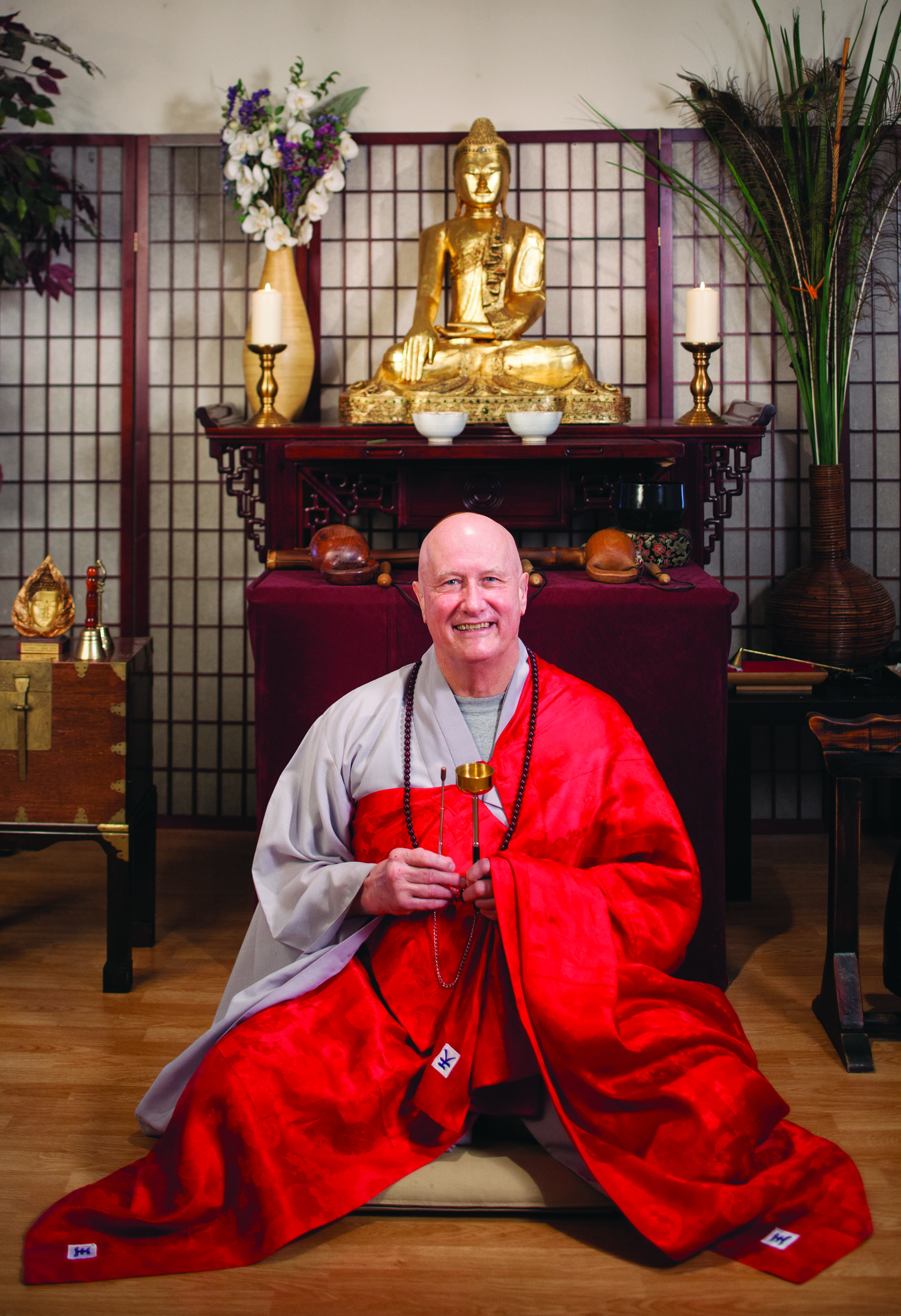

Venerable Hae Doh Gary Schwocho, the abbot of Muddy Water Zen, in Royal Oak, Michigan, and the first American-born to be elected a bishop in the Taego Order of Korean Buddhism, has felt called to ministry since elementary school. Born to parents who were active in a fundamentalist Christian denomination that believes, among other things, that the Pope is the Antichrist, Schwocho strayed from the church while in college and was eventually excommunicated.

Still, the ministry called, and he was on track to become a Presbyterian minister when he attended an introduction-to-meditation retreat in 1987, led by Haju Sunim and Samu Sunim at the Buddhist Society for Compassionate Wisdom in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Schwocho received the precepts from Samu Sunim in 1997 and was ordained in 2003 by P’arang Geri Larkin, Samu Sunim’s dharma heir. The next year, Schwocho converted his garage into a dharma hall and moved the Muddy Water Zen sangha into his suburban Detroit home.

Schwocho calls himself a true Midwesterner at heart: “I’ve been a Michigander all my life and intend on going nowhere else.” But as a bishop in the Taego Order, one of the two main schools of Korean Zen Buddhism, he is also part of an expanding international web of Korean Buddhist practitioners. The Taego Order split from the Jogye Order, the larger of the two Korean Buddhist schools, in 1970, over differences in celibacy requirements for their monastics. Taego monks, like Japanese Zen monks, are allowed to marry and raise families, part of the order’s effort to be truly engaged with the world, although Schwocho himself is now celibate.

During his four-year term as bishop of the North American Parish, Schwocho is responsible for clergy training and lay education, as well as establishing policy that echoes Western cultural values. Under the current Korean rules, gay men and lesbians are not allowed to fully ordain in the Taego Order, and women must remain celibate to be fully ordained. Schwocho hopes to change that.

A veterinarian for 43 years, Schwocho is as committed to relieving the dukkha of animals as he is to helping people. In some ways he has never totally bucked the Christian values he grew up with. Now a minister, albeit in a faith he never expected to follow, he isn’t hard to imagine as the ultimate good Christian neighbor.

—Emma Varvaloucas

You went to a Methodist college in Michigan. Did you grow up as a Methodist? No. I grew up in the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod. Missouri Synod is quite a fundamentalist sect of Lutheranism, where every word of the Bible is the literal word of God. I always wanted to be a Lutheran Missouri Synod pastor while I was growing up, from elementary school all the way through high school. But I also loved animals, so I also wanted to go into veterinary medicine. It came down to a choice between going to a college where I’d study veterinary medicine or going to a Lutheran college. My pastor even took me to a college called Valparaiso in Indiana, trying to encourage me to go there. But I was going with a gal, and she was going to be too far away from Indiana, so I ended up going to Albion College in Michigan, then Michigan State University School of Veterinary Medicine. But always in the back of my mind was the idea that one day I would go into the ministry.

It’s pretty rare for a young boy in elementary or even high school to want to devote his life to ministry. Do you think it’s because you grew up in a fundamentalist Christian atmosphere? That in part may be it. My folks were active in the church and my dad was an elder, but during the week they weren’t the type of people that read the Bible or anything like that. In fact, I did more of that than either of my parents or my sister. From early on, I felt a pull, and when we’d go to church, for me it was just like, “Wow.” I felt it opened me up to another dimension, and I wanted to explore that. I’ve always had this question of why we’re here. What’s this life about if all we do is die at the end? It’s been an enigma for me since I was a young kid. At the time I thought the road was straight in one direction—I thought for sure I’d go into ministry—but it turned out to be all these little craggy side roads and detours. That’s the real path of life.

What was it about the ministry that was especially attractive to you? Working with people, people’s hurts, people’s pain. There are some theologians who are great academicians. They love studying the doctrine and history, and that’s wonderful. But that’s not me. I love to take the teachings and apply them in real life. That’s why I like temple Buddhism—what I’m doing now. I like to be on the frontline where people are in crisis, because maybe I can help them walk through that crisis.

On the Muddy Water Zen website, there’s a quote: “Religion begins with the first cry for help.” Is this how you see it? There are a lot of people who say that Buddhism isn’t a religion because it doesn’t deal with God. But for me religion is a practice that offers a hand when you’re in trouble. It’s not a static thing. It’s dynamic. And, boy, if Buddhism doesn’t do that, I don’t know what does!

So you were brought up as a Lutheran, but then you were on track to become a Presbyterian minister. Why the switch? I was Lutheran through college, and then when I went into veterinary college I strayed away from the church. I had gotten married, and I was busy studying. In the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod, if you don’t partake in the Lord’s Supper every so often they can actually excommunicate you. And I was excommunicated! It really upset me.

After I graduated from veterinary college, my wife and I started looking for a church again, at my insistence. I read about Presbyterians. I read about Baptists. I read about Catholics. I read about Episcopalians. And I finally decided that liberal Presbyterianism—not the conservative Southern Presbyterianism, where it’s like, “This is black and this is white, and never shall ye cross that line”—resonated with me the most. And so we went to a little local Presbyterian church. I became the president of our congregation, and I went on from there to start studying ministry.

Unfortunately, my wife was not on the same page as I was. Her feeling was that the minister is always held in higher regard, that he’s on a pedestal and that he has to watch his every move. Our particular minister could not have cared less. He said, “Look, I’m just a regular guy. I love this work that I do and helping people, but I’m just a regular guy, so don’t put all these expectations onto me, because I’m not going to carry them for you.” That’s the attitude I had too, but she didn’t see it that way. It eventually led to our divorce after 24 years of marriage, once I started going to seminary and she realized that I was serious about it.

Okay, so you were plugging along to become a Presbyterian minister. And then in 1997 you received the precepts and officially converted to Buddhism. What happened? In June of 1997, I had just finished a year of serving as a student pastor of a small Presbyterian church and was moving along in the ministerial ordination process, but my heart wasn’t in it. I wasn’t jumping for joy as I thought I would be. When I was a senior in college I had taken a class about Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam, offered by a visiting professor from India. In fact, we never got to Islam because we focused the whole time on Buddhism and Hinduism. This was in the 60s, the anti-God, anti-authority time. I took this class to piss my parents off—I had no idea what Buddhism and Hinduism even were. But I loved the class. I held onto all the books, and 13 or 14 years later, I started reading them again. I took up meditation on my own, going to the local library and borrowing Hindu books on meditation. I’d sit alone at night in our family room with a candle lit, practicing, and my wife would go up to bed and leave me there. Meanwhile I was thinking, “Man, I don’t know what the hell I’m doing.”

Then one day my wife came to me and said, “I probably shouldn’t tell you this, but there’s going to be an introduction to meditation weekend retreat in Ann Arbor.” So I signed up for it and went to that weekend retreat, which was led by Haju Sunim. It was wild. I loved it. And that started my parallel walks in my Christian practices and my Buddhist practices.

While you were studying both, did you find there was tension between the two? No. I imagine there might be for doctrinaires. But I was trying to get beneath the belief, and I had no problems with doing that. I had heard years before that in prayer we reach out to God, and in meditation God reaches out to us. I always felt like I had a pretty good prayer life, but I never really heard a whole lot back. So I thought I’d try meditation.

Meditation was really valuable to me, and I didn’t see a lot of tension between it and my particular theology. It was another way of opening up to something that was more than me. My theology wasn’t one of “We’re so distanced from God that all we can do is beg for forgiveness and hope that at the end of our lives we’re going to be saved somehow.” My theology was more about oneness. And from meditation I learned that God is not necessarily out there. The divine is closer to us than we think. Meister Eckhart, a Dominican priest and mystic, said, “The eye through which I see God is the very eye through which God sees me.” That’s how close the divine is to us. It’s not that there is a divinity out there, and we’re going to sit here and listen to it. God is not something separate. Or in Buddhist terms, between the absolute and the relative, there’s no difference.

I’m surprised to hear a Buddhist use the word God so much. When you say “God,” what exactly are you referring to? Everyone has a different feeling for what God is and isn’t. It’s the fastest thing that leads to an argument that there is, and it can be a hindrance rather than a help, so I tend not to use the word very much. And as a Buddhist I don’t talk about God at all. But Paul Tillich had a definition that I used to use: “God is the ground of being.” So I’m not talking about God in terms of personhood. There’s just this otherness, this something that we’re all part of.

You’ve lived in the Midwest your whole life, in what I understand is a heavily Christian atmosphere. How do people react when they find out you’re a Buddhist bishop? A lot of my veterinary clients who began with me 35 years ago, have certainly seen me change through the years. And they’re not Buddhist by any means—they’re Christian, and many of them are evangelical Christian. So even though there are a couple who are still praying for my soul because they’re sure that I’m going to end up in hell, they know who I am behind the labels of “Buddhist” and “bishop,” and so we get along marvelously and tease one another. I say, “Well, if I’m going to be in hell, I’ll be with most of my friends, so it’ll be OK,” and they laugh and laugh, and we have a good time.

It really doesn’t bother you to think that these people genuinely think you’re going to end up in hell? No, no. I understand where they’re coming from. And their doctrines say that unless you’re a Christian and you’re practicing in this particular mode, you’re probably not going to make it in the end. Well, for me, I don’t know about the end. The end is right now. Heaven and hell are not some places I’m going to go to later on. Heaven and hell are here right now, and I create them for myself with my own choices.

I gave a dharma talk a couple of weeks ago on “people before principles.” Rather than holding onto principles, it’s always people who are important to me. Principles are manmade, human-made. Where did they come from? They came from causes and conditions.

With interfaith work you look beneath the beliefs. Who is this person really? Just another person looking for some answers and for some help, and trying to get on as best as they can.

Veterinary medicine is definitely an easy job to look at as right livelihood. How does your Buddhist practice inform your work as a veterinarian? It used to be that I felt that I either had to be a veterinarian or had to go into ministry. For years I couldn’t see where they were connected. You talk about tension—that’s where my tension lay. This has been one of my greatest personal struggles—to bring the two together and realize that I’ve been doing ministry all of these years by being a veterinarian.

Have you learned any surprising spiritual lessons from the animals you care for? I’ve learned a lot from the animals. There’s so much more that goes on within animals than we give them credit for. We use different languages, but if you get beneath the language—their growls and their meows and whatnot—there can be a resonance between a person and an animal that is really amazing.

Maybe this is a side step, but there are people who come to temple here who love Buddhism because it’s scientific. They like science and they like provable facts. The Buddha, of course, didn’t get into the metaphysical. He just said, “Here’s what I can show you. Try it for yourself. See if it works. If it does, come follow me.” I don’t disagree with that, but there are so many people who shut themselves off from other possibilities. Through working with animals, I’ve had some experiences that are beyond the grave. I’ve had people say, “Oh, you’re full of shit” when I talk about them. But I feel that too many people, because they think that buddhadharma is so compatible with science, don’t think about otherness, that there’s a mystery, that we’re in a mystery. I’m willing to open myself up to the mystery and say, “You know what, I don’t know all the answers.” Yeah, I’m a scientist. Yeah, I’m a religious person. They’re not incompatible whatsoever. They’re very compatible—it’s just that you have to be willing to open yourself to that mystery.

You say that there’s no tension between being a Buddhist and being a scientist. But how do you reconcile the first precept of not killing with veterinary practices like euthanasia? That’s a poignant and important question. But I’ve come to realize that buddhadharma is all about intention. Intention doesn’t always play out the way you think it’s going to, but if your intention is right and your mindset is not one of anger or ill will or hatred, if the intention is to relieve dukkha, it makes all the difference. Euthanasia is not some casual “Gee whiz, I don’t like my animal anymore. How about you put it to sleep, Doc?” No, no, no, no, no. But you can see when an animal is in an extreme stage of discomfort. After doing this for almost 43 years, I know when that time comes. My intention is simply to relieve their suffering. So I don’t have any qualms about that anymore.

You’re the first American to become a bishop in the Taego order. The order itself isn’t that old, and it hasn’t been around in the United States for very long either. Do you view yourself as a bridge between the order in Korea and the beginning of its spreading to the West? Not really, because there are others who came before me who are the innovators and who are serving as bridges. I think in my role as bishop one of the important things to do is maintain and strengthen our relationship with headquarters in Seoul, because there are some administrators over there who don’t understand that there’s a parish outside of Korea.

At the same time, there is a tension, because there are certain traditions within the Taego order and the Jogye order that are more cultural than anything. Korean culture is not the same as Western culture, and some of the things they hold onto and value we don’t believe are necessary any longer. So I want to gently pull them our way. I’d like to start having them see things through our eyes, see that we feel it’s time for them to give in certain areas a little bit more than they already have.

Are you referring to the rules for LGBT ordinates and the celibacy rules for female ordinates? Are those things something you’re looking to change? Oh yeah, that’s something we’re definitely looking to change. Some folks think that because of these unfair rules I should walk away, and I’m a hypocrite if I stay. Well, I’ve been around the block enough times to know that walking away isn’t going to prove anything. I can be much more effective by staying put and working from within.

When American Buddhists think about Zen they tend to think about Japanese Zen—Korean Zen isn’t as popular here. Is the flavor of Korean Zen different from the Japanese? What I like about Korean Zen is that there’s much more of an earthiness to it. There’s less precision, and things are less black and white. I went to a Japanese Zen retreat in California years ago. Doing their walking meditation, where it takes you ten minutes to walk like, two feet, it was like, “Oh my God. This is even worse than sitting.” And when you sit, you sit a particular way. The Korean tradition is much more forgiving, much more accepting. Japanese clergy wear black and white, I think, for a reason. It’s right or it’s wrong. Korean clergy wear shades of grey. It doesn’t just remind us of cremains [the ashes from cremation of a corpse] and that life is important because you’re going to die—it also reminds us that life is relative. And even though we want it to be black and white, it’s not. So don’t kick yourself so much, and just do the best you can.

Japanese Zen also has much more of an emphasis on koans. In the Taego order and the Jogye order, we don’t go through the 1,700 koans that a lot of Japanese practitioners worry about. There’s one basic hwadu [short question used in meditation]: And what is it? It’s kind of the hook. And what is it? What’s the meaning of our life? What’s the next step? What is it?

You said earlier that your marriage ended because your wife felt that being a minister automatically put you on a pedestal. How do you feel about it now that you’re a sunim, an abbot, and a bishop? I knock myself off the pedestal all the time if somebody tries to put me up there. Nobody’s going to put me on a pedestal. I keep reminding people that I am nobody special. I’m simply a human being serving a particular function within our order. Bishop is just a name.

I love jokes. I love to laugh. In a lot of my dharma talks I like to incorporate the latest joke I’ve heard or read. And we’ve had people come here who can’t believe that they’re hearing a monk telling a joke. These are usually new people who don’t know. They’ve read one or two books about Buddhism, and they expect somebody to float in on a cushion of air and talk real mystically. I break that image pretty quickly, and I have fun doing it.

Buddhadharma is a wonderful teaching, but we shouldn’t make it something it’s not. Because when that happens, it’s not useful anymore. I want it to be useful. And to be useful, it has to be real. I’m real. I’m not pretend. I’m not on a pedestal. I’m just another guy.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.