a problem of shape—

the human life, long, narrow—

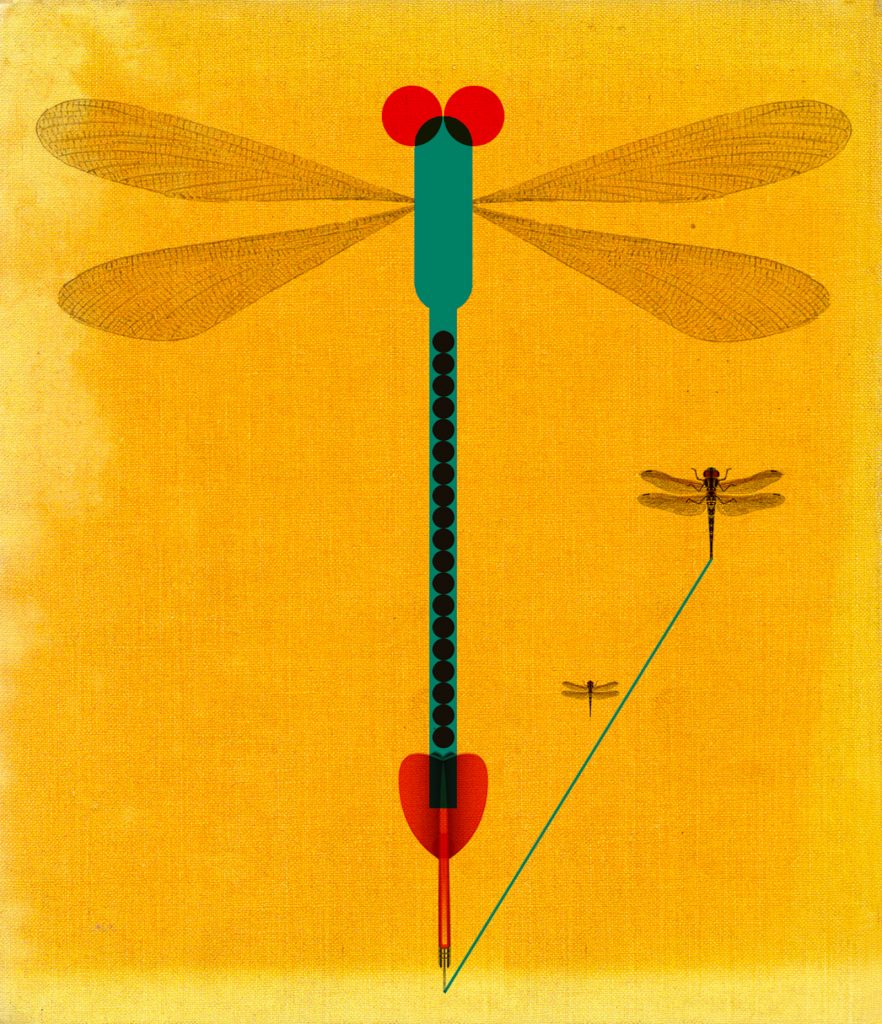

like a dragonfly

–Mariya Gusev

It is unlikely that any English language haiku journal would agree to publish this winning poem. It lacks the earmarks of haiku as a form of literature derivative of Japanese poetry. The poet has chosen the haiku form to express her thoughts about life, but in terms of technique, she has thrown her lot in with Emily Dickinson rather than with Basho. This is haiku as American poetry.

The poem breaks some of the most widely observed conventions of the form. The first line offers an abstraction, rather than establishing a concrete image. The second makes broad generalizations about human life. Only in the third line do we find out what the poem is about. Even then, the season word is used metaphorically. There are no actual dragonflies.

When asked to comment on her inspiration, the poet wrote:

I remembered catching dragonflies as a child and marveling at their sleek, shiny bodies, which although somewhat bendable, were also strong as steel. A haiku formed in my mind as I thought about human life, which is also long (about 80 years on average) and narrow (increasingly disconnected from the rest of nature). Like a tiny metal dart that gets thrown, flying in a straight line for almost a century until we reach the end. A dart that gets to fly through an abyss of loneliness.

Her remarks account for the emotional power of the poem, but not for the paradox of its central image. For if a human life is long, a dragonfly is not. Its length seems long only in relation to its width. “A problem of shape,” she calls it. The life of a modern Homo sapiens is too long for its width, too narrow for its length.

What makes the poem not simply a good modern haiku but a masterpiece of short-form English language poetry is how succinctly it expresses one of our deepest frustrations as a species. In doubling the human life expectancy since the turn of the 19th century, we have stretched it thinner. We live longer on average, but the range of our experience as it relates to the natural world is narrower than ever before. The result is an “abyss of loneliness” we must fly through from one end of life to the other.

I wrote that there were no actual dragonflies in the poem. But that is not quite true. As in Dickinson’s poetry, the symbol is sometimes more real than the thing itself.

Dragonflies are elusive creatures. Difficult to follow as they veer unpredictably, they can flash out of nowhere and vanish just as easily, only to reappear where least expected. Dragonflies have been known to cross oceans in their migrations, and they have journeyed over vast expanses of geological time as well. The earliest fossils of dragonfly-like insects are 325 million years old.

And so, hidden in the poet’s use of the season word is a nod, not only to the evanescent beauty of these small creatures, but also to their vitality and extreme durability over time. If “the human life” really is like a dragonfly, the world may not be done with us quite yet.

♦

The Tricycle Haiku Challenge asks readers to submit original works inspired by a season word. Moderator Clark Strand selects the top poems to be published in Tricycle with his commentary. To see past winners and submit your haiku, visit tricycle.org/haiku. To read additional poems of merit from recent months, visit our Tricycle Haiku Challenge group on Facebook.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.