After thousands of years, haiku is having its day in the sun. Well, maybe not in the sun, but definitely in the soft glow of a digital screen.

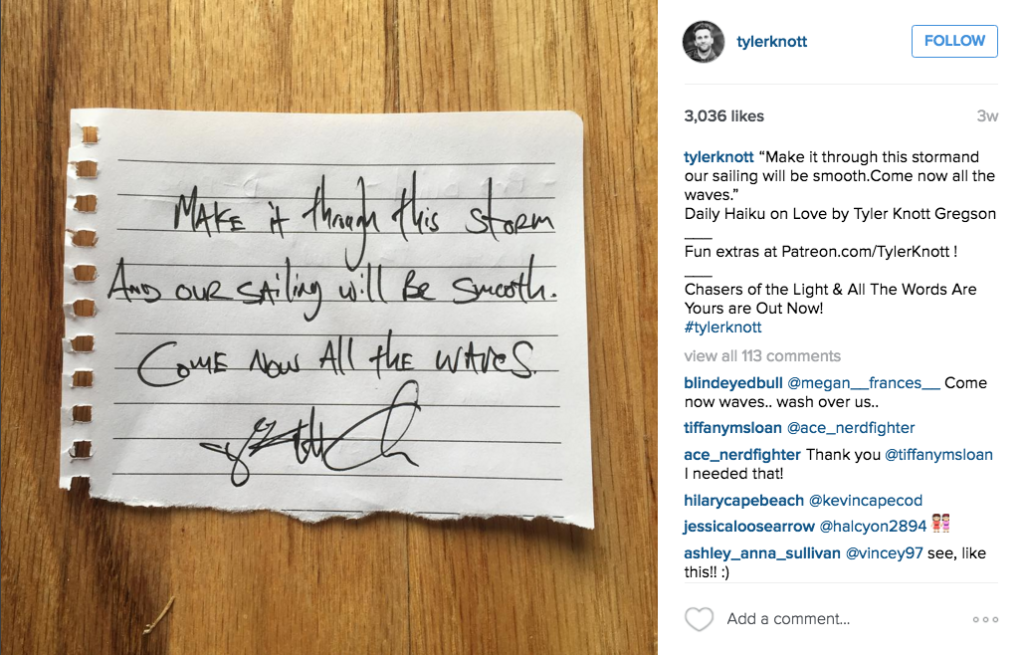

A recent search for #haiku on Instagram returned over 285,750 posts. Many of these posts feature handwritten haiku and haiku superimposed on photoshopped images of mountains and sunsets. On Facebook, a public group called Haiku has over 7,000 members. Many traditional haiku journals also maintain active Facebook pages and Twitter accounts that regularly share haiku from a wide pool of poets. These services have encouraged a renewed focus and attention on short poetry, making haiku more accessible than ever before.

It’s easy to argue that some of these Instapoems, as they’re called, do not honor traditional haiku format. Even though modern English haiku writers have long since abandoned the classic 5-7-5 format (instead writing 1-3 line haiku in approximately 12 syllables), many poems posted online are missing key elements that define haiku: a kigo, or seasonal reference, and a kireji, a word that indicates a sharp transition between two juxtaposed images. Many of these poems are in fact senryu, or short, often-humorous poems that reference human nature. While ancient haiku evoke pastoral imagery and timeless teachings, modern haiku and senryu hold much promise. These poems call our attention back to life as we know it—a rich, layered, 21st century experience worthy of our highest attention.

Many modern haiku poems even share Buddhist teachings by drawing on successful images in ancient haiku. Let’s consider the poem below by Issa, an 18th-century lay Buddhist priest. This rather well-known poem asks us to contemplate those people who provide guidance and direction in our lives as well as the nature of the direction itself:

the man pulling radishes

points the way

with a radish

Now, consider a present-day take on this poem by Alan Pizzarelli. Though his poem reflects a modern experience, the words still honor the integrity of Issa’s original teaching:

the gas station man

points the way

with a gas nozzle

Modern haiku also explore the inevitability of death—a central Buddhist theme. Below, the late renowned poet Nicholas Virgilio describes a brief meditation on his father’s death as well as his own:

adding father’s name

to the family tombstone

with room for my own

Poet Tom Clausen invites us into another moment, one of profound realization about our shared fate:

Going the same way . . .

exchanging looks with the driver

of the hearse

Themes of connection and partnership appear regularly in modern haiku, often coupled with profound self-awareness. In the example below, Francine Banwarth describes the familiar tug of longing:

paper moon

any kiss

will do

In just five words, renowned haiku poet George Swede provides a sobering glimpse into the most intimate of moments:

Leaving my loneliness inside her

More and more modern haiku incorporate technology. Below, Philip Rowland’s poem makes a powerful statement about the extent to which technology enables authentic connection:

eating alone

forcing a smile

for the selfie

While many ancient haiku reflect prayer and religious traditions, modern haiku also incorporate images related to contemplative practices. Some, like this poem by George Dorsty, take a more humorous slant:

am I holding

them correctly?

worry beads

Other poems, such as the one I wrote below, encourage us to be introspective if only to more deeply know our immediate surroundings:

the sink

only drips

during meditation

While the teachings of haiku are undoubtedly valuable, I’ve often wondered how other poets engage with haiku. Years ago, I felt relieved to discover the poem “Japan,” written by the beloved American poet Billy Collins. In the first two stanzas, he writes:

Today I pass the time reading

a favorite haiku,

saying the few words over and over.

It feels like eating

the same small, perfect grape

again and again.

The act of absorbing something tiny and whole—or seeing it, liking it, and reposting it on Instagram—perhaps best describes the power and the allure of haiku: each poem invites readers into a fleeting yet total experience. All haiku—ancient, modern, and digital—attempt to illustrate moments that evoke what it means to be human and what means to be connected with the rest of the world.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.