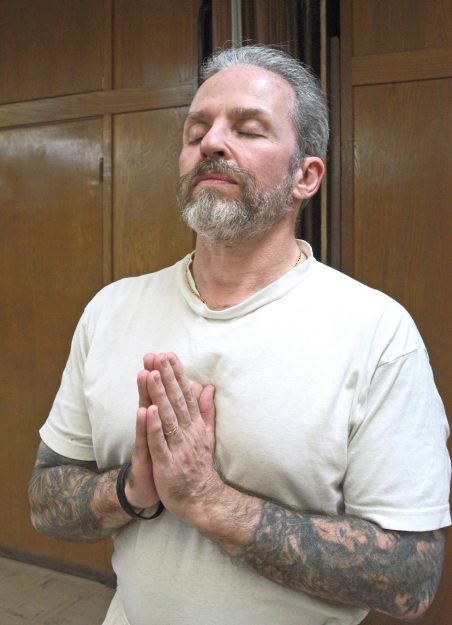

Rusty Trunzo was in prison for over thirty years for committing murder. When he completed his sentence three years ago, he left prison as a radically different man. “The first nine years in there, it was all about staying numb,” Trunzo said. “Using [drugs], you know, and really not getting involved in much of anything.”

But all that changed when Trunzo was transferred to San Quentin, the California prison where the Insight Prison Project (IPP) launched its highly successful mindfulness- and meditation-based prisoner rehabilitation programs 15 years ago. Trunzo, inspired by an out-of-body experience and the book Autobiography of a Yogi, signed up for an IPP class. “And after that’s when I started making the changes,” he said. “Those classes were really instrumental for me.”

Founded by Jacques Verduin, a community organizer and teacher, IPP is an initiative that, in Verduin’s words, “takes some of the dharma and finds a language and application for it that speaks to a multiethnic incarcerated population.” IPP teaches prisoners how to witness their experiences through meditation, cultivating decision-making and emotional-intelligence skills that will reduce the chances of recidivism after they leave prison.

Almost all of California’s prisoners will one day be released. The question is, Verduin said, how do you want these people to be when they are? According to a 2006 study by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 67.5% of inmates return to jail within three years of their release. “We think it’s tough on crime to make these guys face what they’ve done and speak about it in front of a group of other people, and do the work, rather than hide out in these warehouses we’ve built,” said Verduin. “Because the courts address the facts but not the wounds, neither for the victims nor for the prisoners.”

Addressing these wounds is an important part of IPP’s work. Through the IPP classes, the prisoners learn how to deal with their emotional suffering without lapsing in to violence, drug or alcohol abuse, or criminal behavior.

“There’s this sort of perception hijack on who [the prisoners] are because they committed a violent offense,” said Verduin. “But it’s our job to help prisons be a place where we can remind each other of our humanity.” If IPP graduates like Trunzo are any example, the possibility of humanity is a distinct reality.

Trunzo, who likes to classify himself lightheartedly as a “Christian slash yogi slash bodhisattva,” is now a certified drug and alcoholism counselor, and works as a housing coordinator for disadvantaged families in need of transitional housing. And he is just one of the many men— some former life-sentence prisoners— whose lives have been transformed by the meditation and yoga practices that IPP has introduced them to.

“The practice carried me inside, and it’s continuing to carry me outside,” said Trunzo. “This existence is about generating love and compassion and understanding, and as far as I’m concerned, everything else is secondary.”

Jacques Verduin was inspired to work with the prisoners of San Quentin after the Buddhist teacher Jack Kornfield encouraged members of the Spirit Rock Meditation Center community to become more involved with prisoners in the Bay Area. Verduin was also motivated by a dream he had. “I was dreaming about a male buffalo,” he said. “It was standing in a prairie by itself, in a huge empty space.” The buffalo kept turning around and around, pawing the earth in all four directions, looking for the herd, but unable to find it. “That became symbolic to me of the alienation that so many of us feel, the lack of sense of belonging to something greater. And it seemed to me that nowhere else was this lack of connection more strongly expressed than in how we run our prisons.”

Today, IPP holds 20 classes a week at San Quentin, serving some 300 prisoners. Classes include yoga, meditation, violence prevention, and emotional literacy. There are also more specialized courses, such as IPP’s Victim Offender Education Group Program, which brings in victims to dialogue with offenders. Five other California prisons also offer the program.

As IPP’s participants have progressed along their spiritual path, some have helped found additional programs. After one of his fellow prisoners committed suicide, Trunzo started Brothers’ Keepers, a class in which intervention counselors train the men to identify warning signs that an inmate is in emotional crisis.

Just a few months ago, Verduin stepped down as the executive director of IPP (he has been replaced by Jennie K. Curtis) to cultivate a new but related project called Insight Out, which employs former prisoners to work with kids in youth centers and high schools—targeting the ones, said Verduin, “who are on every teacher’s list as the problem kids.”

Insight Out is also collaborating with the Mind Body Awareness Project to provide MP3 players to juvenile detention centers. The MP3 players are prerecorded with stories and advice from the Insight Out men—respectfully known to the incarcerated youths as “OGs,” or original gangsters. The recordings offer comfort to the young people and urge them to change the course of their lives.

Former prisoners like Trunzo who participate in Insight Out also give talks to sanghas about the transforming effect that mindfulness and meditation have had on their lives, and they train new crops of volunteers to go into the prisons and teach.

“Every time I do one of these talks or trainings,” said Trunzo, “it’s like coming to life for me. That’s what I feel I’m really being pulled and called to do. You reach a certain point where your level of understanding shifts and you feel compelled to start giving back what you’ve received.”

Verduin is hoping that this change in understanding will equally inspire practitioners in California to donate to or volunteer for Insight Out. “Somebody was instrumental in connecting you to this practice,” said Verduin. “And you’re grateful that that happened. And so in the same spirit, you’re willing to extend yourself to a group of people, these life-sentence men, that are like the unforgiven. It’s an opportunity to be instrumental in the awakening of those that might never gain access to the dharma if we didn’t go the extra mile.”

The stories of these California prisoners as told by Verduin provide powerful inspiration to go that extra mile: a man nicknamed “Warlord” who used to belong to the Crips raised his hand in one of Verduin’s classes, exclaiming, “I got it! I got it! Hurt people hurt people.” Then another man, nicknamed “The Hulk,” who was Warlord’s apprentice, said, “I got something too! Healed people heal people.” To which Verduin responded, “Wow—there’s my whole program described in eight words.”

To Help: insightprisonproject.org

Reciprocity Foundation

In New York City, the Reciprocity Foundation is empowering homeless teens and young adults to leave the social services system, enroll in college, and start professional careers. Reciprocity takes a holistic approach, offering programs that focus on three areas: career and college preparation, leadership and social entrepreneurship, and integral well-being.

The foundation uses innovative means to ensure success for the young adults who participate. Their Live Well program provides tools to establish healthy living patterns, including counseling, life coaching, yoga classes, support groups, and mindfulness-based stress management courses. Reciprocity also operates a Leadership Institute that invites corporate and community leaders to work with entrepreneurial homeless youth on socially responsible creative projects. Instead of merely getting young people off the street, Reciprocity staff members help participants focus on longterm goals and provide the tools for pursuing creative careers as fashion designers, media activists, public relations specialists, and filmmakers. This year, seven Reciprocity Foundation participants were nominated for an Emmy for their documentary Invisible: The Diaries of New York’s Homeless Youth.

The Reciprocity Foundation is currently developing a holistic center for homeless young people in Manhattan, and is planning to expand its programs to other cities in the near future.

To Help: reciprocityfoundation.org

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.