Buddhists are not vegetarians, nor are they carnivorous. Traditionally, Buddhist monks always got their food by begging, and they always begged for just one meal. You couldn’t beg for a week’s worth and put it in your refrigerator. For each meal, you had to go out and ask for food, and whatever you were given you accepted with deep gratitude, and consumed completely with no waste. Nothing was thrown away. That’s the rule: we eat what is available, with no waste. For example, it would be pretty hard to be a vegetarian if you were a Buddhist in the North Pole. They don’t have many gardens there. If you intend to survive, you’re going to have to eat whale blubber like everyone else. So food is a very funny thing; what you eat has a lot to do with where you are on the planet. If you try to feed whale blubber to somebody on the equator, they would die from the cholesterol in a very short period of time because they’re not burning that energy the way those on the North Pole do to produce heat.

What is appropriate food has a lot to do with genetics, with geography, with what’s available. The Tibetans, for example, had to eat meat. They couldn’t grow many gardens in the high country of Tibet. So, the Dalai Lama eats meat, as do most Tibetan monks. Even those belonging to the most conservative schools of Buddhism, like the Theravadans, will eat meat if they’re given meat. Given a choice, though, we usually prefer vegetarian food. We serve basically vegetarian food at the monastery, except periodically in the winter when people are working outside in the cold chopping wood and need something more than vegetables. If they feel they need more fat in their diet, we’ll serve meat, but there’s always a vegetarian alternative.

There are many good reasons to be vegetarian, hundreds of good reasons: the way animals are treated, the way they’re pumped full of hormones, for example. The precepts, however, are not one of them—”Do not kill” is not one of them. We need to understand that there is not a single creature on the face of this earth that takes a meal without doing so at the expense of another life. We all consume life. That is a fact of life on planet earth. Whether the life is a cow or a cabbage, it is a life. It is a profound thing to take a life, and so the way we do it is very consciously.

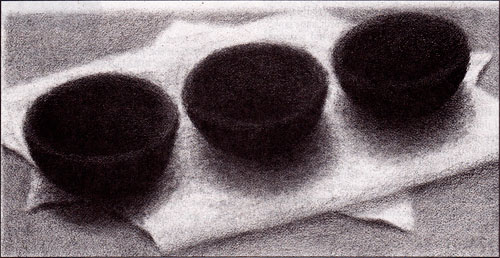

That leads me to oryoki, which is the way we take formal meals at the monastery. Most meals during workshops or during regular practice periods are taken informally, but during sesshin, our week-long silent retreats, most meals are received formally. In the back of the zendo on the shelves are a group of bowls wrapped in cloths, and each practitioner has his or her own set.

When we come into the zendo for an oryoki meal, we all bow together and take our seats. Oryoki is probably the most elaborate ceremony we perform, yet in a sense it is simply the ordinary business of taking a meal. Before we open the bowls, the cook brings in an offering food accompanied by the beating of the temple drum. There is a very dramatic series of drumrolls, each with increasing volume and intensity, while the food offering is being made. You would think that the king is suddenly going to appear, or some profound thing. And that is the point: it is a profound thing. Taking a meal, consuming life, is very profound.

Then the food is brought in. Oryoki literally means “just the right amount.” Someone who is large eats “largely” and someone who doesn’t need much eats just a little. Each person takes just the right amount. You hold your bowl out and as the servers put the food in it, you signal with hand gestures if you want more, or just a little bit, or no more.

When everyone has received food, we chant the Meal Gatha: “First, seventy-two labors brought us food, we should know how it comes to us…” The “Seventy-two labors” refer to the very practical things that bring us food—the seeds in the ground, the labor of the sun bringing it to life, the activity of water bringing it nutrients, the person harvesting it, the person who cooks it, and the person who serves it. All of those labors, all of that work has gone into bringing the food to us. That gets acknowledged personally with the chanting of the gatha. Each person also gives an offering of food from their bowls. That is collected, and we return it to nature. It goes out for the birds—or the cook eats it!—but it doesn’t get wasted.

Then we begin eating. When everyone is finished (and every grain of rice, every morsel, is consumed), hot water is brought in and poured into the first bowl. You clean the first bowl with a rubber spatula, pour the waste water into the second bowl, and dry the first bowl. You then clean the second bowl and the utensils and pour the water into the third bowl and dry the second bowl. Finally, you drink the water from the third bowl, dry that bowl, and then stack the bowls and fold the cloths back up. We feed sixty-five people in forty-five minutes—with no leftovers, no dishes to wash. The process is very efficient, and it’s very conscious. You can’t have an oryoki meal without being deeply aware of every bite of food that you’re taking.

Oryoki is a liturgy in a sense, but it’s a liturgy that doesn’t require formal bowls and a zendo setting. You can do oryoki at McDonald’s. It has to do with a state of consciousness, with the way you use your mind. It has to do with the way you receive food, the gratitude that is felt when you receive food. The Meal Gatha reminds us why we take this food, what the whole point of it is: it is for all sentient beings. Oryoki is about the fact that we consume life, not rocks; we live on life, and we do so consciously and with gratitude.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.