We know where the Buddha was born, where he became enlightened, and where he died. We can even say where he gave his first sermon. But no one can say for sure where he spent his childhood, or where he married and fathered a child, for the precise location of Kapilavastu—the city-state his father governed as leader of the Shakya clan—remains a mystery.

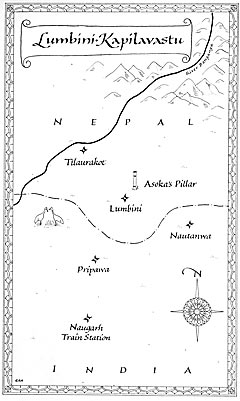

India claims that Kapilavastu is the modern-day village of Piprahwa, a fifty-eight mile drive southwest of Lumbini, the birthplace of the Buddha. Framed by snowy peaks and just four miles south of the Nepali border, Piprahwa is little more than a few buildings and a park with thick-trunked, parasol-shaped trees shading a giant pile of bricks. The soft dirt roads once traversed by chariots remain, and oxen stand stoic against invading armies of flies.

An excavation in Piprahwa between 1971 and 1977 by the Archaeological Survey of India yielded stone caskets, relics (bones), and an inscription plate: “This is the monastery of the Kapilavastu monks.” An urn found in a much earlier excavation also bears an inscription suggesting that relics found therein are from members of the Shakya clan, possibly even from the Buddha himself. The relics and their containers are now on display in museums in Calcutta and New Delhi. Some of the bricks in the pile among the trees were once a stupa, one of the ancient cone-shaped structures that mark a spot associated with a great teacher. About a mile away are two more excavated mounds, the biggest a thick-walled structure that according to local belief was the house of the Buddha’s father. These discoveries led India to proclaim Piprahwa the site of the ancient Shakya clan, Gautama’s home for his first twenty-nine years. Today it is the site of a small Sri Lankan monastery and temple, Mahinda Mahavihara.

In 1899, the British government sent an archaeologist, P. C. Mukherjee, to Nepal to determine the exact location of Kapilavastu. Using epigraphical, literary, and physical evidence, Mukherjee determined that Tilaurakot, sixteen miles from Lumbini and twenty-one miles from Pirprahwa is the real Kapilavastu, and the Nepalese have clung to this ever since. An eerily quiet and shaded meadow far from the path of almost all pilgrims, the Tilaurakot area boasts two pillars erected by the Buddhist king Ashoka, as well as several stupas. The eastern gate of its ancient city walls is thought to be the threshold over which Gautama Siddhartha stepped forth into the world to find enlightenment.

Tilaurakot has a small museum with coins and pottery shards that were found nearby, and it is this pottery that gives Tilaurakot the edge in its claim to be the real Kapilavastu. In 2001, UNESCO and the Nepalese government underwrote extensive digging by two English archaeologists from the University of Bradford. The archaeologists discovered that the ceramic shards were the same painted “greyware” used in South Asia between the ninth and sixth centuries B.C.E. With the age of the town established, and its status confirmed as the only fortified urban site in an otherwise rural area, numerous scholars confirmed Nepal’s claim that Tilaurakot is Kapilavastu. India’s Piprahwa, on the other hand, with its monasteries and Buddhist complex, may actually be Nigrodha’s Park, the scene of many gatherings of the Buddha and his sangha. Ancient texts place Nigrodha’s Park near Kapilavastu. However, nationalism and the prospect of the tourist trade have become factors as important as science in resolving where the true Kapilavastu is. In spite of the recent findings in favor of Tilaurakot, the jury is still out.

While scholars and governments quibble over the relative merits of the competing Kapilavastus, who the Buddha himself was remains a mystery. Legend has it that he was a prince in a palace, protected from all evidence of human suffering by his father, Shuddhodana, king of the Shakyas. But the name Shuddhodana means “pure rice,” suggesting theirs may have been a prosperous rice-farming clan. Scholars now recognize that the lower slopes of the Himalayas at that time were organized into small republics, so the Buddha’s father might likely have been an aristocrat, perhaps a Shakya representative to a ruling council. In the Digha Nikaya, one of the seminal Pali texts, the Buddha’s father is described as a raja or king. But while raja literally means “king,” the term was also widely used as a courtesy to members of respected clans; the word for a true king is maharaja.

Embellishments to the basic story of the Buddha’s life have materialized over the centuries, making it difficult for some to identify him as a mere commoner. But whether he was noble or not, the message of his transformation at Kapilavastu and his decision to leave home in search of ultimate truth remains enduringly the same: any man or woman can open his or her mind to the light of liberation from suffering, regardless of social status or wealth.

After his enlightenment in Bodh Gaya, Gautama Siddhartha traveled back to Kapilavastu several times, always on foot. Many in his ancestral home took refuge in the dharma, including his half-brother Nanda, his son Rahula, his cousins Ananda, Aniruddha, and Devadatta, and a barber named Upali. Shakyamuni’s father, Shuddhodana, and his former wife, Yashodhara, also embraced the Buddha’s teachings.

At the age of eighty, Buddha attempted one last return to Kapilavastu to end his life where it had begun, but on the way he succumbed to illness (probably food poisoning) in Kushinagar. That site has been pinpointed with certainty, but to date, no one can claim to know for certain where Kapilavastu is. The good news, though, is that the dedicated Buddhist pilgrim has two significant sites to explore.

GETTING THERE:

The best time to visit is from October to March. Lumbini has suitable accommodations and is a convenient day trip away from Piprahwa and Tilaurakot. The nearest airport is at Varanasi, 193 miles away. Gorakhpur, 60 miles away, is the nearest city with train or car/driver service. The best choice for a hotel in Lumbini is the Lumbini Hokke.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.