As a college Buddhist chaplain, I always had trouble justifying and explaining to students Buddhism’s apparent end goal of humans ceasing to exist by virtue of no longer being reborn. Bernat Font-Clos (“The New Tradition of Early Buddhism,” Winter 2021) clarifies the dissonance I’ve felt as a Theravada practitioner who is also life-affirming, who believes it’s possible and important to appreciate life’s pleasantness rather than shy away for fear of succumbing to attachment.

Yes, dukkha is cooked into the batter, but it’s not every ingredient. For the first five years of our marriage my wife and I so wanted children; instead we experienced unexplained infertility, two rounds of IVF, and a miscarriage of twins followed a year later by the stillbirth of our daughter.

These years also ushered in their own blessings—it was not complete dukkha. We somehow conceived naturally in early 2021 and welcomed our son Cedar into the world this past November. I’m grateful every day for this gift of life and fatherhood. And, if I’m honest, taking care of this little being is also the biggest source of suffering in my life these days (sleep deprivation, loss of self-care routines, etc.). This has been a powerful teaching for me: that our deepest chapters of dukkha are not without joy, and that our greatest joys are likewise not free from challenge.

Font-Clos carves out important space for critical commitment to both early Buddhism and appreciation of life, and in turn for dukkha to be a thread of one’s experience rather than experience itself.

— Harrison Blum, MDiv, M.Ed.

Director of Religious & Spiritual Life, Amherst College

I wanted to speak up about an article that I read recently about how life “is a dreamlike illusion” or “a mirage” and that we should “let go and rest” (“Freedom from Illusion,” Winter 2021). I have struggled massively with my mental health over the last year and as such have taken a deep dive into Buddhism and regularly read Tricycle. I don’t believe there was any ill intention, but as someone who at times struggles to get through the day without wondering if life is even worth living, I found this article triggering. I understand the message in it, but to say that this is all a dream, an illusion, and a mirage is frankly damaging to someone who struggles to find reasons to live.

I’ve heard that as we progress on the path toward enlightenment we can start to use pain and suffering as grace to help transcend that suffering. Maybe when we achieve that we might share the viewpoint that you published, but for the vast majority of us who are not there yet—and especially those of us who struggle to find real meaning in this “illusion”—hearing that life is a dream does a lot more harm than good. It doesn’t look into the nature of reality, the impermanence of the lives we have been given, the importance of karma, our speech, and actions—to me, it just dismisses our actual human experiences.

I am not attacking anybody; I just wanted to send this letter to bring awareness to how such a statement could be perceived by someone who struggles with their mental health.

—Ryan Morse

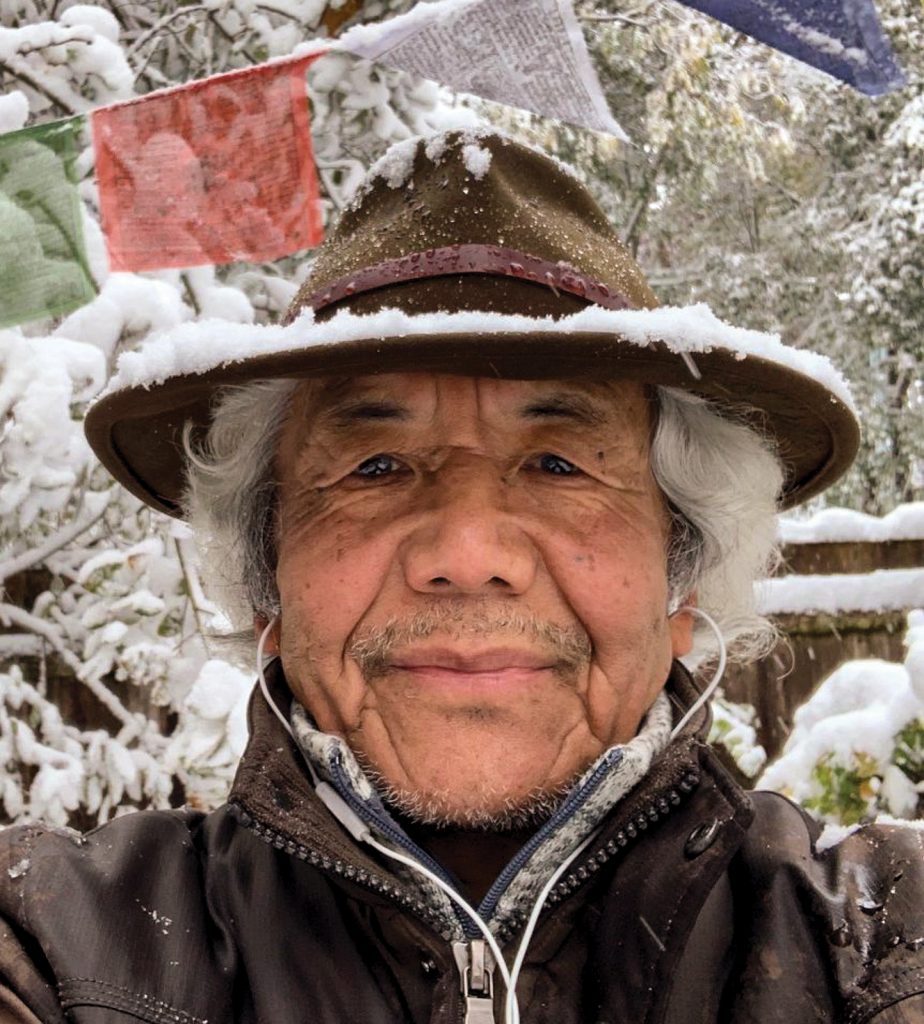

Pema Düddul responds:

When we read or hear that the Buddha instructs us to view the world as an illusion or like a dream, there is a common, and perhaps understandable, mistake we make. We think this means that nothing is real or that nothing matters, that there is no purpose to life. This mistake can cause us to feel demotivated and can even lead to despair.

We can easily see the error of this kind of thinking for ourselves by simply analyzing the nature of illusions and dreams. An illusion is not a hallucination. A hallucination is an experiencing of something that is not there, that is not real, whereas an illusion is a misperceiving of something that is actually there for something that it is not. An obvious example is when someone lost in a desert mistakes heat haze on the horizon for a distant lake. The lake is a mirage, a trick of the eye, but the heat haze is real. The essence of an illusion is therefore misperception, incorrectly interpreting what the senses perceive. Likewise, dreams are real. We all experience them. They are not the same as waking life, however, as they are produced wholly by the mind.

When the Buddha tells us to see all conditioned things as an illusion, or like a dream, he is urging us to understand that our experience of reality, and thus our understanding of it, is distorted and that the source of that distortion is the dualistic mind. He is asking us to apply this understanding specifically to our thoughts and feelings.

The Buddha is not saying that nothing exists. The world exists. Beings exist. Nor is the Buddha saying that nothing matters. The world and beings definitely matter. The whole point of Buddhism is to alleviate the suffering of beings. That suffering is real, but the cause of it is not what we think it is. What the Buddha is telling us is that most of our suffering is the result of a distorted impression of the world and ourselves. This distortion is based on inaccurate sense perception and a mind that fabricates a view of the world and ourselves based on incorrect assumptions.

Our senses and the dualistic mind tell us that we and the things of our world are permanent, solid, separate, and independently existing. The truth is that everything is impermanent, fluid, without independent existence, and deeply interconnected. This is especially true of our thoughts and feelings. Not recognizing how things really are gives rise to negative emotions. Anger, hatred, sadness, despair, jealousy, anxiety, dread, self-loathing, frustration, greed, selfishness: all these arise because we are not experiencing reality as it is, because we are misrecognizing our own nature. But these miserable mind states are not who we truly are. All negative emotions are adventitious, which means they are not inherent to our nature. Because of our misperceptions we have no sense at all of what is truly inherent in our nature and inherent in the true nature of all.

The Buddha does not want us to despair. He wants us to be free of suffering.

Recognizing the illusory and dream-like nature of conditioned things (especially our thoughts and emotions) opens the door to that which is not conditioned: the ultimate nature of our minds and of the universe. This ultimate nature is what we call buddhanature. When we recognize the fabricated nature of our experience, those negative thoughts and emotions cease to arise. When they cease to arise, the radiance of our buddhanature naturally blazes forth. That radiance is joy, love, compassion, and evenness.

Even though it may be challenging to recognize that our perception is distorted, that our understanding of the world is based on false assumptions, if we don’t face this truth we will continue to be plagued by the misery that is negative emotion. On the other hand, if we recognize the fabricated nature of our perception and experiences, we will see through the veil of illusion to what is true, what is real.

That truth, that reality, cannot be put into words, it is beyond concepts, but it has the taste of joy, love, compassion, and total equanimity. That is what reality is. That is what we are. Who does not want to abide in that state? This is what the Buddha wants for us, to abide in the perfection of our true nature, to truly know reality and ourselves. The Buddha does not want us to despair, to feel demotivated. He wants us to be free of the suffering of negative emotion. He wants us to be free of the delusion that currently obscures our perception and obscures what we truly are. He wants us to awaken to our buddhanature and join the ranks of the Victorious Ones. And we can do it in this lifetime. That is the promise of the teachings and practices coming down to us from Padmasambhava and Yeshe Tsogyal. May we all bring that promise to fruition.

♦

To be considered for the next issue’s Letters to the Editor, send comments to editorial@tricycle.org, post a comment on tricycle.org, or visit us on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.