I am a new hospice volunteer and walk up and down the ward, between the two rows of beds with their pale blue sheets and blankets and blue-green curtains that blend with the pale blue-green walls, which echo the green of the garden and the trees outside the windows. The hospice ward is minty, fresh, and light. Smokey, one of the resident cats, finds an empty bed and curls up on it.

“Got a minute?” asks a haggard man with a husky voice.

Of course I do, I have 180 minutes until the end of my shift.

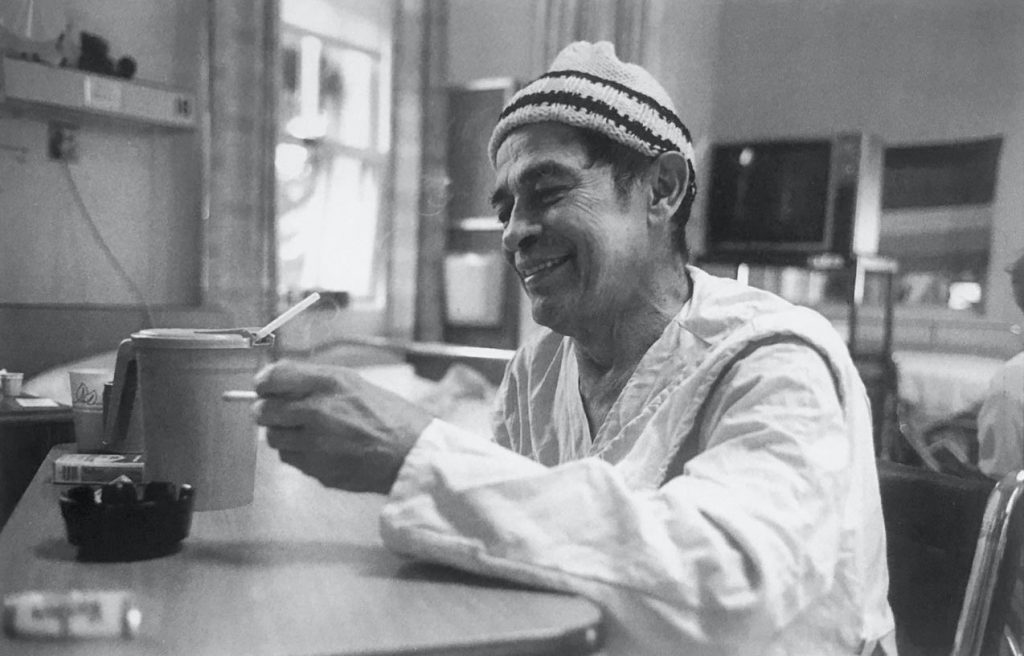

George introduces himself to me. “Sit with me while I smoke,” he says. “Got a light?”

I pull out my new Bic lighter. Many of the people here are smokers, and one of the main rules on the ward is that somebody has to sit with a patient while he or she smokes. The nursing staff doesn’t want them dropping a cigarette or a match and burning themselves or starting a fire. George offers me a cigarette—I don’t smoke—and a soda. He is here at Laguna Honda Hospital in San Francisco because he has lung cancer. He is divorced and his family lives “somewhere in Oakland.” I wonder what to say next. I am a volunteer with the Zen Hospice Project. During the two-week training program Frank and Martha, the project directors, described hospice work as meditation in action. All you have to do, they said, is to sit and be present in the moment. This moment stretches on and on—silent, empty. I feel nervous and awkward, and want to fill it with words.

“Are you a Buddhist or a Zen?” George asks.

“No,” I say. “You don’t have to be a Buddhist or a Zen. Anyone can volunteer, but you have to have a meditation practice and fill out an application and have an interview if you want to do hospice work.”

“That’s a lot to do. Why are you here?” George says.

“I spend a lot of time alone. I’m a writer and I wanted to spend more time around people,” I say.

The volunteers go as quicklyas the patients in the hospice.

Their absence is like a little death. The Zens are right. Everything is constantly changing.

“Everyone here is dying,” he says. “We won’t be around that long. There are other places to be.” His question and remarks are unsettling. Many of the other patients here tell me how much they appreciate the volunteers. Friends and acquaintances call me wonderful for doing this work.

Two years ago my father, two friends, and an ex-lover all died in the same year. I helped care for my father as he lay dying; I changed his diaper, put salve on his dry lips, and fluffed his pillows. I thought I knew about death. But when my friends died I began to wonder. Then I began menopause and turned fifty. My own body was changing. My own death came closer. I saw an ad in the paper: the Zen Hospice Program was looking for volunteers to work with people dying of cancer and AIDS. I feel too shy to tell George this. His cigarette is burning in the ashtray, and he dozes in his chair. I get up and wander again.

“What’s happening?” Ben, the other volunteer who comes in on Thursday afternoons, puts his arm around me. “How can you sit with the people who smoke? That would make me gag.”

Jim waves a cigarette at me and calls, “Volunteer, can you give me a light?”

As I walk to Jim, I see Ben walk up to a bed and offer a massage. I wish I could be as bold as that.

Jim has red hair and a big toothless grin. “Look,” he says, pumping his good arm up and down, ‘Tm getting stronger, Melissa.”

“I’m not Melissa,” I say.

“That’s right, Nancy. Why do I always call you Melissa?” He laughs and puffs on his cigarette. “Guess what?” he says. “I’m not in debt any more. I owed the corner store six hundred dollars for cigarettes and booze, but when the owner found out I had AIDS and was in the hospital, he told me to forget the bill. He sent me some more cigarettes and some cookies. Take some cookies.”

Joe, in the next bed, decides that he wants to smoke too; I move my chair and sit between the beds so I can watch both of them. There is a chain-smoking club here. George, Jim, Kent, Joe, Ron. When one of them lights up, the others start calling and waving their cigarettes. Ron is the prettiest—blond hair, blue eyes, lips as full as ripe strawberries. He is the most restless and the most vocal. He always wants something: a cigarette, a soda, take me for a ride, take me to bingo, get me an ice cream. He hoards his cigarettes and never shares with the other smokers on the ward. I try to avoid him because he is so demanding. I walk down the hallway that leads to the hospice ward and wonder what I will do today. Last week half the beds were empty and most of the people, even the smokers, were sleeping. I spent most of my shift in the garden, picking flowers to put around the ward.

I walk down the corridor that leads to the main room.

“Can you help me, honey?” a woman asks. I look into the single room and see a tiny woman with orange hair propped up in bed. She coughs and sounds like she is drowning in a sea of phlegm.

“It’s stuffy in here. Can you open the window, honey?”

I open the window. “Would you like some company?” I ask.

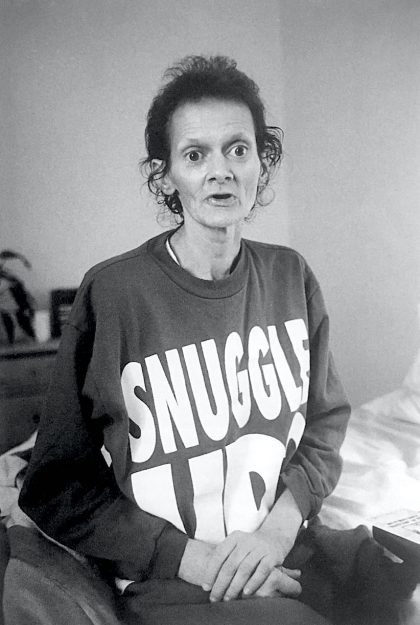

“Oh boy, would I. I have to ring the bell ten times before anyone comes in. I could die by myself in here. But watch me, honey, soon as I get stronger I’m going home. Before you sit down, could you find my bag of yarn, honey?”

A pile of boxes and bags lies in one corner of Lilly’s room; dishes for food and water for her cat are in the other comer. “I’m a recovering alcoholic, honey, and I used to smoke three packs a day. Now all I have is a little emphysema. That social worker wants to close down my apartment, honey. I don’t know why.”

I know why, but I don’t know what to say. We talked about denial during training; denial is one of the stages of death. Most of the people who are referred to the hospice have a prognosis of six months or less to live. A few get stronger and go to a nursing home because they don’t need as much nursing care. Lilly has me opening and closing her window, feeding her cat, calling the nurse to help with her oxygen.

“I have an appointment at the beauty parlor. Can you take me upstairs, honey? My hair is a mess—I have to get it done before I see the doctor.”

I listen to Lilly, hold her hand, take her up to the beauty parlor and think, Perhaps Lilly is right, maybe she will grow stronger and go home.

When I return, the hospice is quiet. Half the beds are empty. Many patients sleep, the ochers have visitors or watch TV. One man mumbles and waves his arms. The sheets are damp and twisted around him and his gown is open. I put a clean sheet over him and reach for his hand. He mumbles, pulls away, and stares at me with wild yellow eyes. I’m glad when it’s time to collect Lilly. “Oh, I’m glad to see you,” she says when I arrive. Lilly looks ravishing. Her hair is arranged in tight red curls, and her nails are painted pink. “I’m bursting, I have to go the bathroom.” We find a bathroom on the fifth floor, but the doorway is too small for Lilly’s wheelchair and she’s too weak to walk in.

“Let’s find another one,” I say.

“That’s O.K., honey, I’ll just pee in my diaper. The girls can change me when we get downstairs.” I wonder who is taking care of whom. I come here co serve the people on the hospice ward, but I often feel as if they are taking care of me. George and Jim are always offering me cigarettes, cookies, and sodas. Joe tells me to get something for myself when I bring him hot dogs from the cafeteria. Now Lilly tells me not to worry.

I leave Lilly in her room and walk down the main ward; I want to talk to George before I leave. I go to his bed. He is sleeping, and his breath rattles like pebbles on a beach. Oh well, I think, I’ll talk to him next week.

Tuesday evening I go to the biweekly support meeting for the volunteers. Sometimes there is a guest speaker, a doctor or a nurse who talks about caring for people with AIDS, or a monk from the Zen Center who talks about caring for the dying as medication in action. Tonight the meeting is a gathering of old and new volunteers. (An “old” volunteer is someone who has been doing the work for six months or more.)

I learn that Lilly, Kent, and Rick died over the weekend. George died Monday night. My first reaction is surprise. Lilly had just had a manicure and a perm and was ready to move back to her apartment. I was sure George would be there on Thursday afternoon. Then anger jumped in: why didn’t he wait for me? I wanted to talk to him and clarify my reasons for doing “the work,” as the Zens say. He was the first person I sat with in the hospice; I wanted him to be there when I returned. I feel empty. I feel as though I have lost more friends. I have lost an opportunity to learn more about George and Lilly.

This is typical of the way I live my life, I think, as I sit and listen to Frank read the list of those who have died during the past week. I am always procrastinating—I’ll start my diet after Christmas; I’ll call my mother tomorrow; I’ll read War and Peace next summer. My life is an exercise in procrastination.

Some of the volunteers talk about their experiences sitting with someone who died. “Pat and I were sitting in the garden having this great philosophical discussion and suddenly he gasped and died,” Ben says. I feel like I am missing something. I’m jealous.

Mary, who was in my training group, introduces me to an “old” volunteer. “This is my sister,” she says, “we were in training together.” When Mary calls me her sister I feel warm inside and squeeze her hand. We are sisters, and the other volunteers in our group are also my brothers and sisters. There is a bond between us because we went through training together.

“I am happy to see so many new faces here tonight,” Frank says. “There are forty people here tonight. We are growing. That’s wonderful.”

I look around the room. There were thirty people in my training group, and now, after a month, some faces are missing. Where are James, Anna, Elizabeth, Kurt, and Beatrice? The volunteers go as quickly as the patients in the hospice. Their absence is like a little death. The Zens are right. Everything is constantly changing. There is no security, no permanency. There is only the present moment. There is only now.

Thursday afternoon the hospice is noisy. There are ten televisions blaring, each one tuned to a different station. Visitors walk up and down the ward. Tom, in Bed 10, is the only person without a visitor, so I sit with him. His skin is sallow; his breathing is shallow and hesitant; his eyes are wide open, staring. He looks like he is watching a horror movie. His hands are ice-cold.

I was surprised by the intense anger I experienced during the guided meditation. . .When confronted with my own death I was furious.

Joe, the social worker, stops by the bed. “Some patients like to be alone when they’re dying,” he says. “There’s a new patient, a Hispanic woman, who needs some company. She doesn’t speak any English. You speak Spanish, don’t you?”

“A little,” I say. “I don’t think Tom wants to be alone. We don’t come into the world alone. Why should we be alone when we leave? My aunt was alone when she died. Her children weren’t there. My mother says she wishes she had been with her sister when she died.”

Joe frowns and moves away. I think I’ve stepped on his toes, but I feel comfortable sitting with Tom, holding his ice-cold hand and trying to stay in the moment.

Richard, one of the orderlies, comes bustling by. “Jim wants a smoke,” he says, “and there’s a Mexican lady in Bed 20 who needs some company.”

“But—” I begin. Richard doesn’t let me finish.

“I know he’s dying of AIDS, but there are other people here who need attention.” Richard always acts like he’s the doctor in charge of the ward. I remind myself that we are not here to be comfortable or to argue but to serve the patients. I go to Jim’s bed. I put a cigarette between his fingers, which are stiff and bent from arthritis.

“Are you mad at me?” he asks as I light his cigarette.

“No.”

“You didn’t answer when I called you,” he says. “You look mad.”

“I didn’t hear you,” I say. Jim is surrounded by empty beds. George, Kent, Rick—all his neighbors have died during the past week. “Don’t worry Melissa—er, Nancy. This is my last cigarette. I’m not going to die like George and Kent. I’m going to quit smoking, and I’m exercising. See?” Joe pumps his good arm up and down. “Can you gee me a glass of water?”

I pour a cup of water and hand it. to him. “Is it fresh?” he asks.

“Yes,” I say.

“Well,” he says, “did you slap it?” I smile and chuckle and Jim shakes with phlegmy laughter and shows his toothless gums. “I knew I could make you smile,” he says. “I’m getting some new teeth and glasses and going to physiotherapy. Raul, the orderly who comes in at night, is helping me to walk. I’m going to get an apartment and have my own attendant.”

I want to believe him. When I first came to the hospice he was pale and slept a lot. Now he is glowing like the marigolds on his bedside table and is as talkative as the birds in the garden.

When Jim finishes his cigarette, I return to Bed 10. It’s empty. Tom’s body is not there, and the bed is made with clean sheets. Everything that belonged to him is gone—his clothes, his flowers, his pictures. I feel dizzy, confused. The hospice staff has erased every trace of him. Once again I am cheated of a chance to say good-bye.

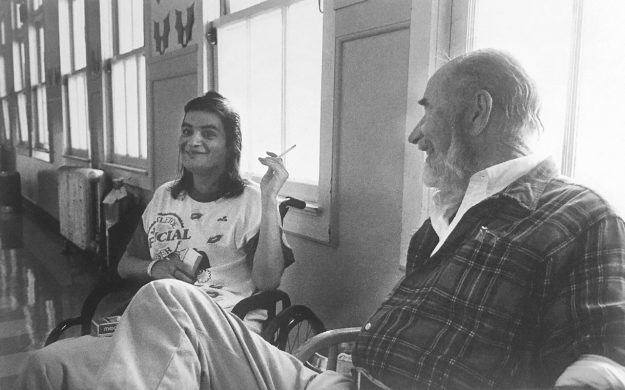

Kim, the volunteer who comes in on Thursday morning, tells me Ron is not allowed to smoke in bed anymore.

“He’s in a bad state,” she says. “He keeps saying he wants to leave and go home to Florida. He dropped a cigarette in his bed and burned himself and burned a hole in his sheets. Now he has to sit up in a chair if he wants to smoke.” Marta, the head nurse, gives me the same message.

The moment I enter the ward Ron beckons me. I am shocked at how much he has changed since last Thursday. He is thinner; his bones look like they are going to break through his skin. His eyes are red-rimmed, his skin sallow, and he talks in a hoarse whisper.

“I want to ask you something,” he whispers. “Come closer.” I stoop down beside his wheelchair. “Wait till she goes away,” he says, glaring at the nurse who is distributing little paper cups that contain medications.

“Can you buy me a lighter?” he asks. “They won’t let me smoke in bed anymore.” He sounds like he is going to burst into tears.

“No, Ron, I can’t do that,” I say. I’m surprised at myself. Usually I hesitate and stutter when I say “No.” During our training we role-played difficult situations we might face in caring for people who are dying. The training must have prepared me to face Ron.

“Please, Nancy, please. I’ll give you money. I got fifty dollars you can have if you just get me a lighter so I can smoke in bed. I can’t get out of bed every time I want a cigarette.” Tears slide down Ron’s face. I say no again.

Ron doesn’t stop. “I want to get out of here,” he says. “This is supposed to be a hospital, not a fuckin’ jail. I want to go home. Take me for a ride.”

Jim and Joe are waving cigarettes and calling me. Marta tells me that there are two new patients who want some company. I ignore them all. I feel tender toward Ron and his pain and protective of him. Ron is fading faster than the flowers on his bedside table. I don’t want to miss this opportunity to spend some time with him.

During our training we were taken on a guided meditation in which we learned that we had terminal cancer and were going to die. Frank talked us through the whole process, from the initial diagnosis of cancer to telling our families and leaving our jobs, to lying on our deathbeds in a hospital. I was surprised by the intense anger I experienced during the guided meditation. I was angry that I had cancer and angry that my life was being interrupted; I was angry at being dependent on others and losing control of my own life. When confronted with my own death I was furious. Now I cannot dislike Ron for being angry and afraid.

I help Ron put on his jacket and tuck a blanket around his legs. We go for a walk. It’s a warm spring day in February, but the garden is too cold for Ron. He wants to go to the gift shop. I hold my breath when he looks at the lighters behind the counter, but he is more interested in some porcelain music boxes.

“Which one do you like?” Ron says. “I’ll buy it for you.”

“No, Ron, you keep your money,” I say. “You’ll need it for your trip.”

“I want to buy you something,” he says. We are not supposed to accept gifts from the hospice patients. Ron is insistent. I accept a pack of Dentyne chewing gum.

We sit next to a steaming radiator on the fourth floor. I chew my gum and Ron smokes. Outside the window there is a tree full of chattering birds. We sit in silence. I still have not learned how to sit and be in the moment. I want to chatter like the birds.

“What kind of birds are they?” I ask.

“Finches,” he says. “When I go to Florida I’ll see lots of them.”

The crazy woman who hangs out on the fourth floor and bugs people for cigarettes sneaks up on us. She grabs the cigarette out of Ron’s hand.

“Hey, give that back.” I jump up and try to snatch the butt from her hand. “Never mind,” Ron whispers. “She needs it more than I do.”

I wheel Ron back to the hospice ward and help him back into bed. His pants are wet so I get him some clean pajamas. The outer layers of skin on his buttocks are worn away; his flesh is raw and red.

“Good-bye, Ron,” I say, shaking his hand. Part of me wants to complete the visit with him, to tie up loose ends; the other part thinks, You’re going to make him think he’s dying if you act like this. I have a feeling that I won’t see him again. I am so tired that I take a cab home from the hospice.

Two days later Frank calls me to tell me that Ron died. That evening I slip a small bottle of cognac into my coat pocket and climb up Golden Gate Heights, the highest hill in my neighborhood. The houses and street lights of the Sunset and Richmond districts sparkle below me. The waning moon travels toward the Pacific Ocean. I toast Ron with the bottle of Courvoisier. “Now you are free to go home,” I say. This time I don’t feel so sad and empty.

***

I walk through the hospital to the hospice ward, wondering what I will do this afternoon. There have been so many deaths recently that more than half the beds are empty. There are no more flowers left to pick in the garden. I see Joe, the social worker, walking toward me. He looks as though he is carrying the whole world on his shoulders.

“I’m having a bad day,” he says. “Mike has been on the edge for days. I think he’s going soon, but I don’t know when. Do you think you could sit with him this afternoon?” Joe plays with his beard. He sounds like he is apologizing for asking me.

“Of course I’ll sit with him,” I say, glad to have my afternoon planned out.

When I enter the volunteer lounge, Kim, the volunteer who comes Thursday mornings, gives me the same message. “He is so light, so wonderful,” she says. “I wish I could stay. But I have to go to work.”

“Don’t worry,” I say. “I’ll sit with him.”

Usually I become so involved with what is happening on the main ward that sometimes I forget there are three other rooms in the hospice. Mike is in the room with five beds. I go there first.

“Hi Mike,” I say, touching his cold hands. I pull up a chair, but I want to run away. He looks so cadaverous. His skin is dirty yellow and sinks down around his bones; his breath smells like garbage and dirty laundry; his eyes are red-rimmed and staring. Mike is in a coma. I want to leave, to run away. I force myself to sit there. Then I want to get my journal so I can record Mike’s passing. No. I stop myself. What would I miss if I were writing? I remember what we learned in training. Stay in the moment. Notice what is around you.

“I like your tattoos,” I say, touching his cool flat arms with the dark blurry pictures on them. “I have a tattoo too, but it is not as big and grand as yours are.” Mike’s eyes are open wide, staring up and beyond me. When he breathes his chest moves up and down. Up and down.

I begin to notice how beautiful Mike is. His eyes and mouth are open wide like my father’s and Tom’s were, but Mike’s expression is different. My father looked angry and Tom looked terrified. Mike’s expression is joyous and peaceful. There is a postcard-size picture of Jesus above Mike’s bed. Christ has a golden halo around his head and he is looking up with an ecstatic expression on his face. Mike looks like the picture of Jesus; he has the same golden glow. I notice the light on the planes and angles of Mike’s body, the coffee can filled with paint brushes on the bedside table, the empty canvas at the foot of his bed.

I remember a quotation from the writer Meridel LeSueur, “The body repeats the landscape,” and notice how gnarly Mike’s collarbones are, like the roots of a tree. His rib cage rises like an escarpment above the dry lake of his sunken stomach. When Mike swallows or breathes his whole upper body moves. Under the sheets, below his waist, nothing moves, as though death has already crept into him through his feet and is crawling up into his body.

I tell him how beautiful he is. “You outshine Jesus,” I say.

His breathing begins to slow down. I wait anxiously for the next breath. I begin to cheer him on, as if we’re at a World Series game, the bottom of the ninth inning and the score is tied.

“Come on, Mike, breathe,” I whisper. Then realize I’m being silly. The man is dying from AIDS; he wants to let go. Mike snorts, closes his eyes and mouth, opens them. His chest stops moving up and down. I don’t hear any breathing.

I sit with Mike. I don’t want to tell anyone that he is dead. They might come and move his body and remake the bed the way they did with Tom. I want to sit and say my good-byes to Mike. I stroke his forehead, touch his knotty arms, take the picture of Jesus and put it on his chest. Then I go to tell the head nurse.

Kim is right, Mike is wonderful. I feel that I caught some of his peace and joy. He must have lived well to have died with such acceptance and grace. After I call Kim and Joe to tell them about Mike’s passing, I walk past sleeping people and empty beds to Bed 20 at the back of the ward.

“¿Hola, coma está?” a woman sitting in a wheelchair asks.

“Bien. Me llama Nancy,” I say in my halting Spanish.

“María,” she replies. “Sientate.” She points to a chair and offers me some cookies.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.