I looked around the hall at all the other meditators, sitting so quietly, with such dignity. Suffering arises from getting caught up in stories and illusions—I hoped that somehow this insight might release me from the turmoil in my mind. Freedom and joy arise from remaining present, I reminded myself, but it was futile. Before I knew it, the fantasies whirled me off again.

Several weeks before arriving at this Vipassana retreat, I had met a man who seemed to be exactly what I was looking for. In our few casual encounters, something had clicked, and I was infatuated, now utterly carried away by desire and delicious fantasies.

I was in the throes of what has come to be known as a Vipassana Romance, a state of mind that feverishly builds an enticing and erotic relationship with someone we barely know. In the course of a few hours of meditation, I had lived through courting, marrying, having a family with this man—over and over, in various versions.

No matter what I tried, this industrial-strength Vipassana Romance withstood all my strategies for letting go and returning to the here and now. I tried doing long walking meditations on the snowy paths surrounding the retreat center. I tried to relax and direct my attention to the breath, to note what was happening in my body and mind. I could barely complete two cycles of mindful breathing before my mind would once again return to its favorite subject. I saw us meditating and then making passionate love. I imagined that we’d hike to the top of Old Rag Mountain, revel in the hints of early spring and in the possibility that we were, indeed, soul mates. As my mind churned relentlessly onward, I felt self-indulgent and ashamed of my lack of discipline. Craving is the cause of suffering, I’d remind myself firmly. What was wrong with me? Why couldn’t I just detach, observe it, let it go?

I saw us meditating and then making passionate love.

After several days, I had a pivotal interview with my teacher. When I described how I’d become so overwhelmed, she calmly asked, “How are you relating to the presence of desire?” I was startled into understanding. Her question pointed me back to the essence of mindfulness practice: It doesn’t matter what is happening. What matters is how we are relating to our experience. For me, desire had become the enemy, and I was losing the battle. She advised me to stop fighting my experience and instead investigate the nature of my wanting mind. Desire was just another passing phenomenon, she reminded me. It was attachment or aversion to it that was the problem.

Without a doubt, I had been swinging between feeling possessed by desire and ashamed of my weakness. That I could be freed from suffering by gently allowing the desire and investigating it with awareness suddenly made sense and offered hope. Years later, I would call this capacity to see clearly the nature of our experience and to hold it with compassion “Radical Acceptance.” At that time, however, I didn’t yet know the treasures this practice would yield when applied to the intensity I was feeling.

Over the next few days of that retreat, each time I realized I’d been lost in one of my flights of romantic illusion, I would note it as “erotic fantasy” and pay close attention to the sensations in my body and the emotions that were arising. No longer trying to avoid my immediate experience, nor getting lost in it, I could notice exactly what was happening. I would find myself filled with waves of excitement, sexual arousal, fear. As I practiced experiencing these feelings without judging them, I could begin to explore them further. What lay at the core of this desire? What was I really longing for?

As I gently allowed the pressing ache in my chest to just be there, it revealed itself as a deep grief for all the times love had been possible—with friends, family, teachers, lovers—and I had held back from its fullness. I moved back and forth between erotic passion and this profound grieving. The stories and fantasies kept arising, but because I was no longer judging them I was better able to notice the feelings they awoke in my mind and body. Yet I was still in some way holding on, trying to control the intense desire with a running commentary on what I was experiencing. In one of my favorite lines of poetry, Mary Oliver writes, “You only have to let the soft animal of your body / Love what it loves.” I knew I was longing for love, but I didn’t know how to open myself to its presence.

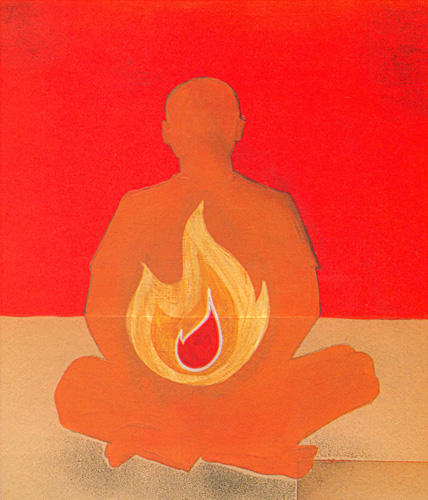

Late one evening I sat meditating alone in my room. My attention moved deeper and deeper into longing, until I felt as if I might explode with its heartbreaking urgency. Yet at the same time I knew that breaking through my resistance to this experience was exactly what I wanted. Instead of focusing all that longing on a particular person, I wanted to experience the immensity of its reach. I wanted to dive into longing, into communion, into the love I knew was its essence. I invited the longing—”Go ahead, please. Be as full as you are.” I knew then I could finally let go. I put my head in the mouth of the demon. I began to say yes, surrendering wakefully into the wilderness of sensations, surrendering into the very embrace I was longing for. Like a child finally held close in her mother’s arms, I relaxed so fully that my sense of all boundaries of body and mind dissolved.

In an instant, I felt as if my body and mind were expanding boundlessly in all directions—a flowing, changing stream of vibration, pulsing, tingling. Nothing separated “me” from this stream. Letting go entirely into rapture, I felt as open as the universe, wildly alive and as radiant as the sun. Nothing was solid in this dazzling celebration of life energy. I knew then that this was the fullness of loving what I love.

Over the next few days, each time I opened deeply to the force of longing, I was filled with a refreshed and unconditional appreciation for all of life. In the afternoons I would go outside after sitting and walk in the snowy woods. I found a sense of belonging with the great Douglas firs, with the chickadees that landed and ate seeds from my hands, with the layered sounds of the stream as it flowed around ice and rocks.

Rumi writes:

A strange passion is moving in my head.

My heart has become a bird

Which searches in the sky.

Every part of me foes in different directions.

It is really so

That the one I love is everywhere?

My Vipassana Romance had not been the enemy after all—the intense desire I felt was a contracted form of love. By meeting it with radical acceptance, neither resisting nor grasping after it, the contraction began to reveal the loving awareness that is our very essence. Like a river releasing into the sea, the wanting self dissolves into the awareness that is simply life loving itself. The one we love is everywhere. By wakefully inhabiting our longing for the beloved, we are carried into the arms of love itself.

♦

To read more on the topic of desire, see the special section on desire, The Riddle of Desire: Introduction.

Rumi poem from Love Poems of Rumi © 1998 by Deepak Chopra, M.D. Reprinted with permission of Harmony Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.