It is a daunting task, trying to capture a sublime being on the page. In fact, in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, if someone is to compose a namtar—a sacred biography—the writer must have certain enlightened qualities equal to that of his subject. This is not a namtar, and I have none of his qualities, but nonetheless I will make an attempt to describe E. Gene Smith of Ogden, Utah, a very great man.

On the day Gene Smith passed away, December 16, 2010, the news reached me at a monastery in a remote part of east Bhutan. Even out there in the hills, the monks knew of him and felt the great loss—his reputation is golden and far-reaching like the sun. Please allow me some hyperbole here. Gene, subtle and humble, did things with his precious human life that cannot be overstated. Many say that he was the man who saved Tibetan Buddhism. And yet when I try to recall his face, I see him sitting at a cocktail party with a Sarah Palin mask perched on his head and a goofy, semi-toothless grin on his face. Gene didn’t take himself too seriously, but his life’s work has had enormous and serious consequence.

In January 2009, I accompanied Gene to Bodhgaya, India. It was his first trip back to the place of the Buddha’s enlightenment in more than 30 years and would be his last. He was on his way to accept an award from the Nyingmapa sect of Tibetan Buddhism. Twenty-six heads of the sect, representing over 300 monasteries, had convened and decided to present Gene with a lifetime achievement award for his work in serving Tibetan Buddhism through preserving and making accessible the literature of the tradition. The nominating committee included Chatral Rinpoche, Tsetul Rinpoche, Shechen Rabjam Rinpoche, Dzogchen Rinpoche, Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche, Tarthang Tulku, Ladakh Choje Tulku, Sogyal Rinpoche, and many other masters of meditation. These lamas don’t routinely act with such coordinated unity. Gene was “terribly moved” by the news and graciously accepted their invitation to the ceremony, though his health was already failing.

Gene and I had arranged to meet at the new domestic terminal at Indira Gandhi International Airport in New Delhi. I found him seated in front of McDonald’s near a group of Buddhist pilgrims and Indian businessmen, reading Sarah Vowell’s book The Wordy Shipmates, about an entirely different set of pilgrims, the Puritans who set out to establish the American colonies. He was sipping black coffee, looking ordinary as ever, very professorial with his wispy hair and tweedy jacket. His conventional exterior— the lumbering posture, the silly grin, the shuffling walk—seemed a masterful disguise to veil the highly accomplished bodhisattva that he really was.

He would have swatted me with his book if he had ever caught me saying something like that. Gene was humble beyond humble, humble without trying. I loved that he was reading American history and not some esoteric text. He was famously well-rounded in his interests, which made him all the more accessible. His sisters said that he had mastered the Romance languages and Latin by the end of high school and then spent his tuition money on parties.

A dense fog rolled in, shutting down all rail and air transport throughout the region, delaying our flight. It was a boon and a blessing to have three extra hours of his company all to myself, to listen to his amazing tales. Gene knew everything about everything, especially Buddhism–not just Vajrayana but all schools, all sects, all forms. I only had to ask one leading question, and then out would come his fascinating yarns about lamas and yogis. At Gene’s memorial at St. John the Divine in New York City in February, anthropologist Charles Ramble recalled the first time he met Gene: three hours into a meeting that was meant to last half an hour, he was still “pestering” Gene with questions. He said all subsequent meetings for the next 20 years had the same flavor. He, like many of us, was completely “gluttonous” for Gene’s time. It’s a good word. Gene’s brilliance, his capacity to remember and recall, his willingness to engage—it was a feast.

Finally the fog lifted, and we were packed into a plane with seats fit for the hips of a fashion model. Gene didn’t complain for one moment, not even when we were parked on the tarmac for another two hours, cramped, girded by armrests. I wanted to protect him from all this, it seemed so unsuitable. It would have been easy to get him a seat in first class if I had put on a memsahib act. Do you realize who this man is? But I looked at him with a side glance, and I knew he would never have allowed me to make a big deal. His humility had a wrathful quality. As did his generosity (my attempt to pick up the tab for our plane snacks yielded a heart-stopping look of fury). So we sat tight and I felt the weight of my mission.

Related: Found in Translation

Once we arrived in Bodhgaya, I scurried around like a maniac, trying to appear to be useful. In the company of Gene, I suddenly found my efficiency had evaporated like ice in the desert. I had the pull of a fruit fly. The only benefit I brought to the situation was the fact that I had a working mobile phone, which he could use to call his friend Mangaram back in Delhi. The cheerless environment of our hotel seemed to have no effect on him; he carried the dignified, leisurely air of a retired general. Several other hotel guests detected that there was something special about him. There were quick bows and introductions and communication gaps.

I was itching to tell them the story.

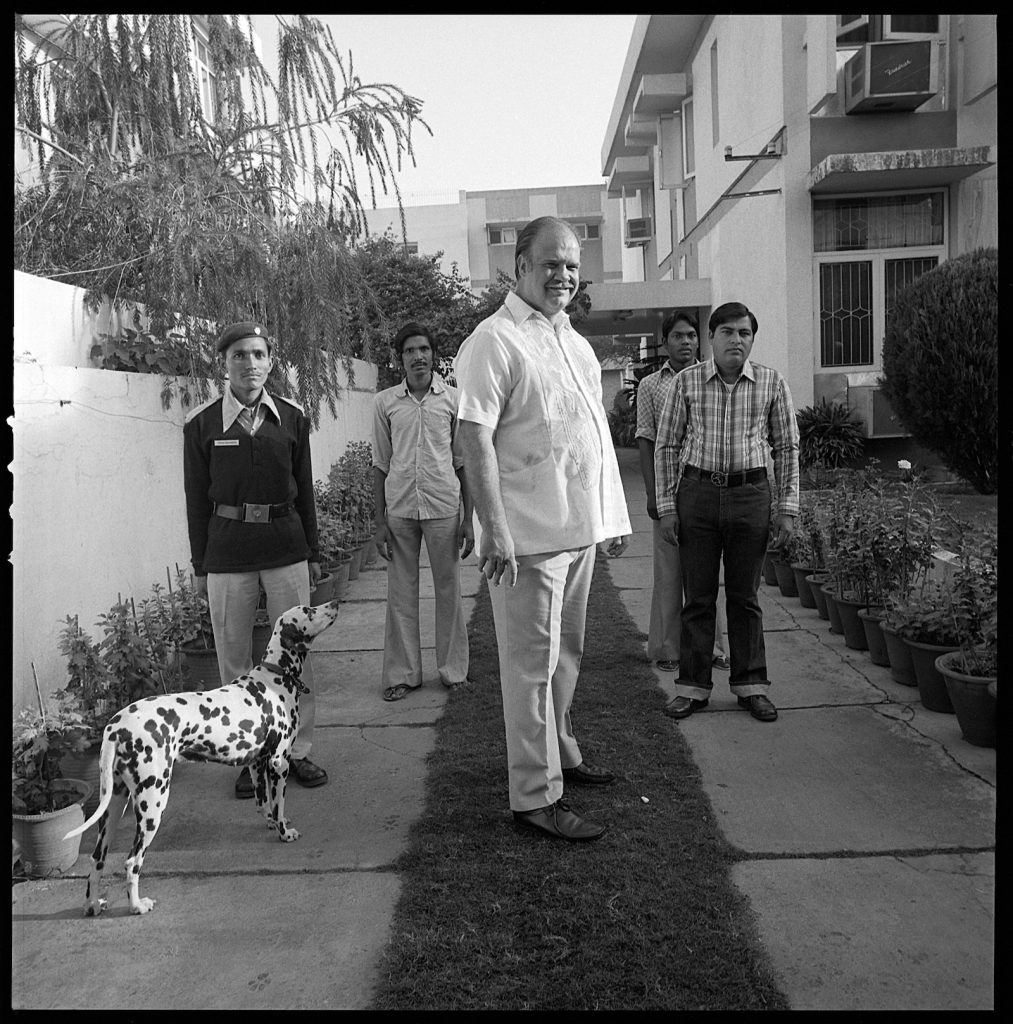

In 1965—after completing an advanced study of Pali and Sanskrit at Leiden University in the Netherlands—Gene Smith moved to New Delhi on a Ford Foundation fellowship to study with living exponents of all of the Tibetan Buddhist and Bönpo (the religion of pre-Buddhist Tibet) traditions. During this time, Gene lived in a grand house as guest of the Indian Secretary of Education, Dr. Prem Kirpal. “I had become a member of his family,” Gene said. Which is not surprising: Gene was like everyone’s favorite uncle.

After the conclusion of the fellowship, his teacher Dezhung Rinpoche, whom he had met at the University of Washington, advised him to remain in India and study with Geshe Lobsang Lungtok (Ganden Changtse), Drukpa Thoosay Rinpoche, Khenpo Noryang, and the teacher who would become his chief guru, H.H. Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche. So Gene stayed in India, and in 1968 the Library of Congress approached him to work at their New Delhi office.

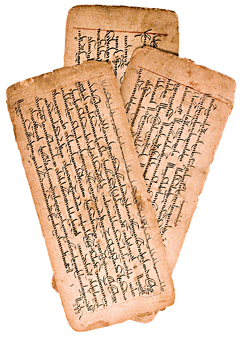

The job presented an enormous opportunity for Gene, which he turned into his life’s work. During the Cultural Revolution, the Red Guard set entire libraries of sacred Tibetan texts on fire. The loss was staggering. Some libraries took weeks to burn. Not only Buddhist texts went up in flames but also encyclopedias detailing ancient cultural practices for everything from medicine and science to ethics and aesthetics. What wasn’t destroyed had to be kept hidden. Rare texts were buried, tucked into sleeves, wrapped in burlap, stored in damp boxes, sunk in rivers, and otherwise dispersed in the chaos. Gene wanted to see these surviving cultural treasures collected, restored, preserved, and catalogued. His new position at the Library of Congress gave him the means to do it.

As a U.S. government official, Gene received the keys to a flat in the Golf Links neighborhood, and he opened his door to the Tibetan diaspora. Though his official duty was to oversee the completion of computer romanization schemes for various Asian languages, he was keen to use his position for an even greater good. He skillfully employed U.S. Public Law 480, also known as the Food for Peace Act, to fund a text preservation program and immediately put out the word that he was paying top dollar for the right to copy Tibetan texts.

The refugee community began to come out of the woodwork—not just Tibetans but Sikkimese, Bhutanese, and Nepalis—with their precious pages, often just a fraction of original collections. They would bring the original manuscripts and blockprints to Gene. If the text was not available in a Western collection, he would purchase as many as 20 copies. This would allow the publishers, often lamas, to print many more copies, which would be distributed to the Tibetan community for the cost of the paper. The rest of the copies went to the Library of Congress and other academic libraries participating in the program.

Meanwhile, Gene’s house became a lama crash pad. Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche stayed with him whenever he came to New Delhi. “I collaborated with the Bhutanese Embassy on such visits because my house was neutral when there were political problems between the Tibetans and the Bhutanese,” Gene told me. “I would turn the house over to Rinpoche and his party. It was such an incredible honor.”

The lamas were impressed and even a little awed by Gene and his knowledge, not just in Tibetan but in Sanskrit and Pali as well. “Some Tibetans used to say that he must have been a Tibetan in a past life and come back as this white man,” said Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche, who was a young tulku living in India at the time. “There was one Lama Phutse who was very well known for his grammar, and even he was intimidated by Gene.”

Related: What’s in a Word?

Though he eventually left India, Gene’s campaign to catalogue Tibetan texts went on for the next 25 years. In 1985 he was transferred to Jakarta, Indonesia, where he continued his work in text preservation. “I was quite happy to be transferred, because I had developed too large a network of responsibilities in India as a government official,” Gene recalled. “But I could easily return to India to see my teachers from nearby Jakarta.” In 1994 he was assigned to the Middle Eastern Office in Cairo. In 1997 he took early retirement from the U.S. Library of Congress and moved to New York.

But he didn’t stop working. In 1999, Gene and his friends founded the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center with the goal of creating the world’s most comprehensive digital library of Tibetan Buddhist and cultural literature. All the texts that he had helped save were now to be scanned, formatted, and made available to anyone who wanted them. Since its founding, TBRC has digitally archived more than seven million pages of Tibetan texts. Now monks from any Tibetan Buddhist lineage— from even the smallest monasteries—can plug in a TBRC hard drive loaded with Buddhist texts and access their most profound practices and teachings. I’ve witnessed the delivery of these hard drives—a little box that contains the entire canon, passed into the hands of an abbot. It takes a moment for the monks to realize what a treasure it is, and then a wave of appreciation washes over them. Those moments are what Gene’s life was about. “If it wasn’t for his effort, we would have lost so many texts,” Dzigar Kongtrul Rinpoche said. “It’s had a domino effect on the preservation of dharma. If these texts weren’t available, then we wouldn’t have the benefit of study, initiations, and transmission. He has singlehandedly done this.”

Just weeks before he passed away, Gene went to Nepal to meet Dzongsar Khyentse Rinpoche to discuss their latest collaboration, a project called 84000: Translating the Words of the Buddha, which is putting in place a 100-year plan to translate the Kanjyurand Tengyur (the Tibetan Buddhist canon) for the first time. It’s a visionary project designed to preserve the authentic buddhadharma even through the darkest aeons.

It was because of this vision that the Nyingmapa were honoring Gene in Bodhgaya. The ceremony was scheduled for the afternoon of January 22. The day opened with a chill, a fog, an inscrutably white sky. Amid a throng of pilgrims, we circumambulated the temple, led by Orgyen Tobgyal Rinpoche. More than 13,000 monks and nuns were chanting the Manjushrinama-samgiti as we walked, 160 verses and mantras of the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. Then Orgyen Tobgyal interrupted the chanting to introduce Gene. Thousands of eyes squinted with curiosity. Who is this white man? Why are they interrupting the puja? But as Rinpoche explained who this great man was, their curiosity was satisfied, and a respectful silence was followed by genuine applause.

Shechen Rabjam Rinpoche joined us on the west side of the temple, under the Bodhi tree where the Buddha attained enlightenment. As thousands more watched, Rabjam Rinpoche presented Gene with a giant bronze gong, the Sambhota Award. A long line of lamas, tulkus, and khenpos approached with white silk scarves, placing them around Gene’s neck one by one. Several stopped the procession to personally thank him for all he had done. Gene listened closely, always interested to hear how the TBRC system was being used, if there were any glitches, if they needed anything else from him. By the end of the procession he looked like the abominable snowman, the lumbering walk, the hundreds of white scarves draping his body. It was hot; the fog had burned off, and the sun was beating down.

I scrambled ahead to see if there was a place to sit at the next stop. All I could think about was how the great man’s shoes were on the other side of the temple, and how there were so many steps to climb back up to the outer kora, and how Gene had probably had enough of the pomp. When we finally connected with our footwear and made it to the rest area, Gene looked exhausted and pale. I wanted to make it better, but there was nothing I could do. As we parted the next day, I felt the awkward grasping feeling I get when I say goodbye to my guru. It was the last time I saw him.

I selfishly wish that Gene had been more selfish, that he had taken better care of his physical health so that we could have all benefited from his presence just a bit longer.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.