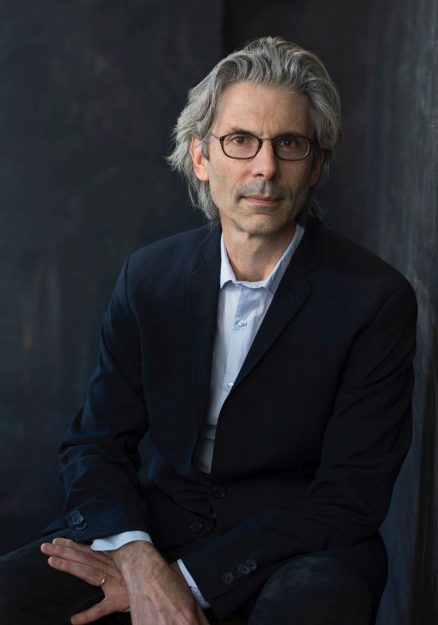

Mark Epstein, MD, has been exploring the territory where Buddhism and psychotherapy meet for several decades. His many books on the convergence have helped define what amounts to a subgenre in both fields. Epstein’s investigation of Buddhism predates his work in psychotherapy, so the dharma has always influenced how he views his interactions with his patients. It was reassuring to him, he says, that he could bring the Buddhist way of listening—simply being with his patients, what he calls simple kindness—into the psychotherapeutic way of listening, and start to use them interchangeably. This interplay is a major theme of his new book The Zen of Therapy: Uncovering a Hidden Kindness in Life (Penguin Press, 2022), in which he reflects on a year’s worth of therapy sessions. In this conversation with Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, Epstein discusses the role of no-self in therapy and the polarity between doing and being, a concept that he attributes to both Donald Winnicott, a major influence on his work, and Buddhist thought.

Your latest book, The Zen of Therapy, is a departure from your other writings about Buddhism and psychotherapy. This time, you talk about your own process. The question that people are always asking me—and that I’m always trying to avoid—is “How do you bring your Buddhist experience into psychotherapy? Do you teach your patients to meditate? Are you asking them to be mindful? Do you sit quietly with them?” And I always answer, “No, I’m just being a therapist.” But I’m trying to be myself. So somehow, if Buddhism has influenced me, it should be coming through.

I’ve written a lot about translating Buddhist thought into the psychological language of the West, but this time I decided to pay attention to the details of the individual psychotherapy sessions and try to write down, as literally as possible, what happened in sessions where my Buddhist inclinations contributed to the therapy, even in a small way.

Over the course of a year, I accumulated notes from around 50 of these sessions with different patients. It was kind of a mosaic picture of a year of therapy, which happened to end just before the COVID-19 pandemic. I didn’t read over any of the cases until the year was up, and then I showed it to my editor. I really trust her. She said the through line was really me, not the random selection of patients. She told me to go through each one and write a reflection so that readers could see what was going on in my head while I was being the therapist. I liked that, so that’s what I set out to do.

You write about how the British psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott had to stop interpreting for his patients because he was interfering with the patients’ own process. Can you say how to be with a patient without interpreting everything they say or do? Winnicott says something like, “I realized that I was interpreting mostly to impress myself, but the patient could experience that interpretation as a kind of intrusion.” Things finally started to open up for me as a therapist when I stopped interpreting so much and just let myself be there. That seemed very Buddhist to me. The concept in psychoanalysis about how and when to interpret centers around tact, which is another version of the Buddhist notion of right speech. We all can see what’s wrong with the people we’re close to, but how often is it helpful to tell them what’s wrong with them? Tact is very important in our relationships, including the psychotherapeutic one.

I set up this polarity in the book between doing and being, an idea that comes from Winnicott but is also a Buddhist idea. This is not to devalue doing but to say that doing isn’t everything. There’s this other quality to life that has to do with being that’s also an interpersonal experience. When I’m able to simply be myself with my patients, that quality of attention or awareness or empathy—in the book, I call it simple kindness—is transmissible. Sometimes it can be absorbed by the patient, who might need that quality in their experience.

You quote Gary Snyder, who years ago wrote in Tricycle that “within a traditional Buddhist framework of ethical values and psychological insight, the mind essentially reveals itself.” What is happening when the quality of being allows the patient that space for the mind to reveal itself? I love that about the mind revealing itself. While I was deeply inspired by my Buddhist explorations, which did happen way before I even began my training to become a psychiatrist, that way of working is part of the psychoanalytic tradition, even going back to Freud. In psychoanalysis, the patient is lying on the couch without looking at the therapist, so that the analyst is simply listening and the patient is listening to themself, to their own mind (or unconscious, as Freud talked about it). That was one of the parallels that I saw originally when I started my training. The analytic attitude and the method of free association or evenly suspended, free-floating attention was remarkably similar to the mindful attention we learn about in Buddhism. It was very reassuring to me that I could bring the Buddhist way of listening into the psychotherapeutic way of listening and start to use them interchangeably.

“Things finally started to open up for me as a therapist when I stopped interpreting so much and just let myself be there. That seemed very Buddhist to me.”

You explore the Buddhist teaching on no-self in relationship to psychoanalytic theories of self. In particular, you ask, “if inklings of no-self are not necessarily signs and symptoms of developmental deficits but also windows into underlying truth, how are we to proceed?” When I was growing up, I was always worried that my self wasn’t “self” enough. Where was I? I was preoccupied with that question. I couldn’t help comparing myself with the people around me, who look like they have bigger, better, and more real selves than I do. You could call it anxiety or insecurity. But this self that we’re brought up in the Western world to think should exist, it doesn’t really exist in the way we imagined it, which is what the Dalai Lama always says: It’s not that there’s no self, because that’s ridiculous. You’re you, and I’m me. But the self doesn’t exist in the way we imagined it does. Winnicott always said that most people can’t really get out of their childhoods without creating a “false self” or “caretaker self” that tries to take care of either the intrusive or the abandoning environment of family life.

All of those ideas were swirling around when I was writing this book: What if the self doesn’t have to be what we think it should be? What if we were correct in wondering about it even from a very young age but had to push all that away in order to function? And then Buddhism or therapy comes along and says, relax about all that and just see what’s there. Try to find it as it really exists, not as you think it should.

You quote your friend and former therapist Michael Vincent Miller as saying that Buddhism and psychotherapy “both aim for the restoration of innocence after experience.” Can you say something about what that means? When he said that to me, I didn’t even know what it meant, but I knew it felt profound. Especially in the psychotherapy world, we’re led to believe that experience is everything—that we’re supposed to learn from experience, and that’s what life is about. But then I think of the koan: what was your face before you were born?

When Ram Dass first found out that I had become a psychiatrist, he said, teasing me a little bit, “Mark, are you a Buddhist psychiatrist now?” I said, “I guess so.” And he said, “Do you see the patients as already free?” I think I do see them as already free. It’s the idea that there’s a hidden kindness in life or that buddhanature is inherent to who we are.

Experience layers us, and we do learn from it, but we also have to defend ourselves against experience and the ways we start to develop ideas about identity and who we are, who the other person is, and so on. Our original innocence gets covered up and lost. When we talk about the feeling in meditation of coming home or being at peace about ourselves, there’s some reconnection with that innocence. I think that’s what Michael was getting at.

I’ve often had difficulty reconciling a psychological orientation and Buddhist practice, but you seem to hold both in balance. For instance, you talk about the oceanic feeling and Freud’s take on that, which you don’t dismiss, while understanding its value from a Buddhist perspective. I don’t know how much your readers know about what Freud meant by the oceanic feeling. He had a long correspondence with a French poet named Romain Rolland, who was a student of Ramakrishna and Vivekananda and told Freud a lot about what happened to him in meditation. Freud wrote that Rolland’s meditation experiences reminded him of a young child at the breast and that they were seeking a restoration of the limitless narcissism of the infant. I think that that’s partially true.

On meditation retreats, if we’re lucky enough, we have these blissful experiences. That’s one of the things that we keep coming back for. If you really look at what they are, how addictive they can be, and how people get trapped in seeking them, those retreat experiences do have a lot of that blissful feeling of the infant at the breast, the restoration of limitless narcissism. That’s part of their power. I always see that as part of the concentration practices, the samadhi practices. They give you that holding environment for the mind that has an infinite quality. But it’s not solely the experience of the infant at the breast; it’s also the experience of the mother holding the infant. Once we start to use the accumulated samadhi to investigate the nature of mind, we become much more like John Cage, who’s hearing everything and allowing everything in the way a mother hears and holds a baby. It’s the maternal quality or the parental quality that is also oceanic. Trying to figure out how to talk about that was interesting and fun for me.

You just mentioned John Cage, whose ideas appear throughout your book. You’re working with the art of therapy, and in a certain way you’re performing an art that is similar to Cage’s; it’s a spontaneous, unblocked opening. That’s the improvisational nature of therapy. That’s one of the things that the process requires. That might just be the way that I work, but I think it’s proven to be an important capacity to bring to the encounter. It takes a kind of trust, too—to trust my own mind without trying too hard to find the right interpretation but rather to use what comes up in a judicious way to engage, provoke, and support a patient.

I imagine early in your career as a Harvard Medical School–trained psychiatrist you thought you needed to know answers and to give your patients answers. In any event, you seem to have come to this place where it’s ok if you don’t know. The thing about becoming a psychiatrist via the medical route is that they don’t really teach you anything about being a therapist. They teach you about diseases, and then one day, you’re the psychiatrist. It’s not like with a surgeon where you can assist and watch how to do it. You have to go with the patient into the room and be the therapist with hardly any education on how to do it.

For me, that was good because I had to figure it out for myself. I already had the Buddhist training, so the best I could do was to try to deploy for the patient what I had learned for my own mind. That set me on this path that we’re talking about now. I’ve had good therapy teachers since, but they were all supportive of not-knowing as the foundation of the relationship.

That really comes through in the book. It really comes through how much I don’t know. [Laughs.]

No, no. [Laughs.] That you’re comfortable when you don’t know, and you can relax into that. It’s exciting to me. It’s a mutual discovery. That’s what therapy is all about.

♦

Adapted from an interview with Mark Epstein by Tricycle’s editor-in-chief, James Shaheen, for the Tricycle Talks podcast.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.