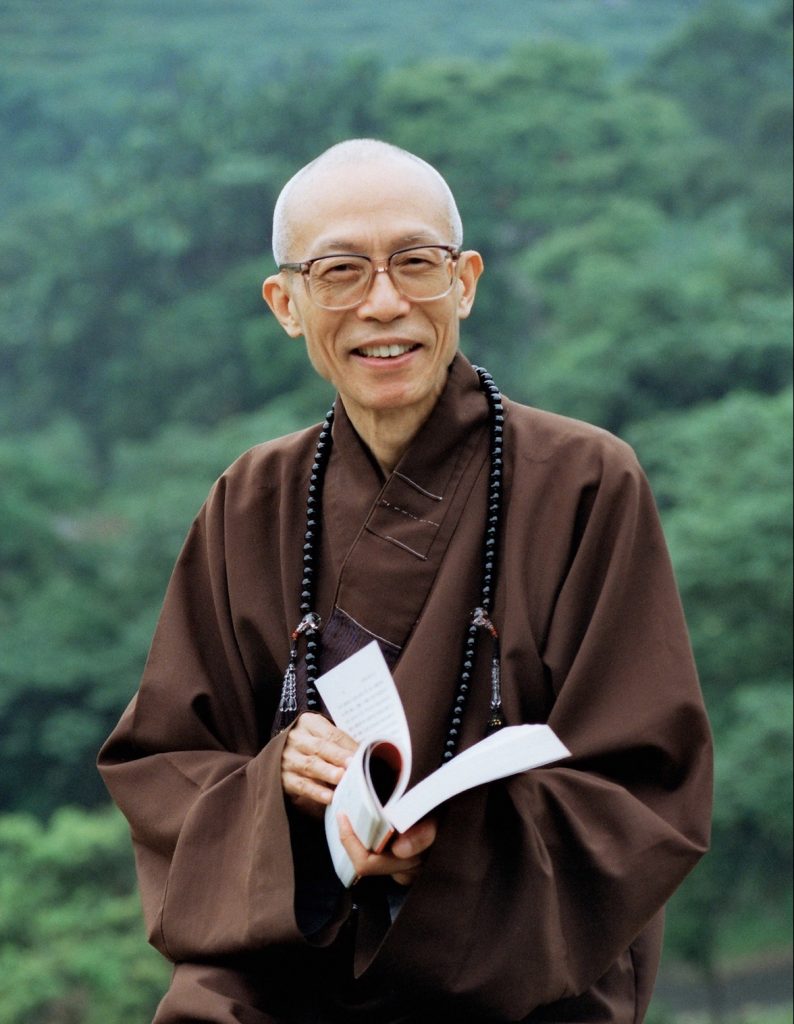

Master Sheng Yen has dedicated his life to spreading the teachings of Chan Buddhism in China and in the West. In this excerpt from his new autobiography, Footprints in the Snow, Master Sheng Yen tells the story of his arrival in New York and how he learned to live without a home.

After I resigned from my post as an abbot in Taiwan, Dr. C. T. Shen [a cofounder of the Buddhist Association of the United States] brought me back to New York to spread the dharma there. My return to the United States did not restore me to my former position of strength, however. There was no room for me to live at the Temple of Great Enlightenment, which was occupied by nuns. I stayed at Shen’s villa, named Bodhi House, on Long Island and traveled back and forth to the city. But I wanted to move out because I was too far away from my students. Shen told me, “If you move out, I can no longer take good care of you.”

“That’s okay,” I said. “I will wander.”

I had no money for rent, so I slept in front of churches or in parks. I learned how to get by from three of my students, who had experience living on the street. They taught me to find discarded fruit and bread in back of convenience stores and food markets. They showed me that I could make a little money here and there from odd jobs, sweeping up shops or tending a pretzel stand. I learned that I could store my things in a locker at Grand Central Terminal and wash clothes at a laundromat.

Related: Portraits of the Homeless

My students pointed out the fast-food restaurants that were open twenty-four hours, and they told me that I could spend my nights at these places, resting and drinking coffee.

I wandered through the city, a monk in old robes, sleeping in doorways, nodding with the homeless through the night in coffee shops, foraging through dumpsters for fruit and vegetables. I was in my early fifties, no spring chicken, but I was lit from within by my mission to bring the dharma to the West. Besides, what did it matter? The lessons Dongchu had taught me made it a matter of indifference to me whether I slept in a big room or a small room or in the doorway of a church.

Some people may have felt pity for me, but I didn’t pity myself. I didn’t feel that I was unlucky. Some people feared me and worried that I would ask for money or other help. I decided it was best not to call on anyone, although I did accept some offers of help. I spent nights at the apartments of my followers. Master Haolin welcomed me and let me stay at his monastery in Chinatown. But I did not want to stay there too long, because I did not know if I would be able to repay him for this service. I preferred to wander.

This may strike some of you as strange—that a friend and fellow monk would let me leave his monastery to live out on the street. But Haolin had a very small place without much income. When I lived there, it was an added burden on him. If he was wealthy and had a big place I would have felt differently about imposing on his hospitality.

I think that being out on the streets was a good thing, because it taught me not to rely on anyone and pushed me to find my own place to propagate Chan. There is a long tradition of bodhisattvas enduring difficulties as they spread the dharma. Shakyamuni Buddha taught that to be a great practitioner, a bodhisattva, you do not look toward your own happiness and security. You only wish for sentient beings to cease suffering. In India, Buddhist monks had to travel to areas without Buddhism, and they would inevitably encounter resistance. When they arrived in China, Confucianism and Taoism were dominant, and the Confucians wanted to keep the Buddhists out, especially the monastics. Shakyamuni Buddha believed that if you could withstand difficulties, you would be able to inspire others and thus influence them. Ordinary people just want life to be smooth, without problems. But Buddhist practitioners have a different attitude. They are ready to endure many difficulties if they are in the service of transforming others.

Related: Homelessness Into Home

How do we endure hardship? Master Mazu taught that it is necessary to have a mind of equanimity. This means always maintaining a calm, stable mind, which is not ruled by emotion. When you encounter success, you don’t think that you created it. Don’t get too excited or proud of yourself. Your success happened for a reason and came to pass because of many people and circumstances. If you work hard at something but find that too many obstacles prevent you from accomplishing it, you may have to give up. In that case, you shouldn’t get depressed. Conditions aren’t right. Perhaps this will change, perhaps it won’t. You are not a failure. Becoming upset only causes suffering.

To be a great practitioner, you do not look toward your own happiness and security.

Keeping a mind of equanimity, though, does not mean being inactive or passive. You still need to fulfill your responsibilities. Master Xuyun said, “While the business of spreading Buddha’s teachings is like flowers in the sky, we ought to conduct them at all times. Although places for the practice [monasteries, retreat centers] are like the reflection of the moon in the water [referring to the fact that they are illusory and impermanent], we establish them wherever we go.” This means that these jobs are illusory, but we still need to do them. Sentient beings are illusory, but we still need to help deliver them. A place of practice is like the reflection of the moon in the water. It’s not real, but we still build monasteries so we can deliver sentient beings. This is our responsibility. We must try our best to fulfill our responsibilities, without being attached to success and failure.

Chan masters apply the mind of equanimity in all aspects of their lives. If they don’t, they are not truly Chan masters. In my time of wandering, I kept a mind of equanimity. I didn’t think of myself as homeless. I thought of Master Hanshan [1546–1623], who lived on Tiantai Mountain. He used the sky as his roof, the earth as his bed, the cloud as covers, a rock as a pillow, and the stream as his bathtub. He ate vegetables if vegetables were available. If rice and vegetables were available in a monastery, he ate that. If nothing was available, he ate tree leaves or roots. He felt free and wrote beautiful poems.

Beneath high cliffs I live alone

swirling clouds swirl all day

inside my hut it might be dim

but in my mind I hear no noise

I passed through a golden gate in a dream

my spirit returned when I crossed a stone bridge

I left behind what weighted me down

my dipper on a branch click clack

When you have nothing, you are free. When you own something, then you are bound to your possessions. I felt very happy. I did not feel that I had no future. In fact, I felt my future was rich and great indeed because I had students. I still had a mission to fulfill. I just did not know where I would sleep at night. I knew that I was much better off than homeless people, who really did not have anything and were without a future. And I knew that I would not wander forever.

My life is very different now. I have met with world leaders and given a keynote address in the General Assembly Hall at the United Nations. My disciples include high-level officials in Taiwan. I was received as a VIP in motorcades in mainland China and Thailand. I am venerated by my followers. People feel that if they don’t treat me this way, it’s not right, but it does not make any difference to me whether they treat me this way or not. I am famous today but tomorrow, when I can no longer do what I do now, I will be forgotten. How many people have their names remembered in history? Fame, like wealth and power, is illusionary. So a mind of equanimity is necessary in all circumstances.

There is a Chinese saying that goes: “After experiencing wealth and property, it is hard to return to poverty.” This is true if you don’t have a mind of equanimity. If you can maintain a mind of equanimity, you are free, no matter what the conditions.

Thank you for subscribing to Tricycle! As a nonprofit, we depend on readers like you to keep Buddhist teachings and practices widely available.